They’re cheaper and faster than the standard PCR test but will they help Australia reopen? Your quick guide to rapid antigen tests.

For our free coronavirus pandemic coverage, learn more here.

Generally, whenever someone is tested for COVID-19 in Australia –behind the long queues to the Q-tip and then the ping of results to a phone many hours later – are lab workers poring over tiny particles collected from the slime in your nose, hunting for the tell-tale genetic code of the virus. But in the United Kingdom, you can pick up a home testing kit at a pharmacy, swab, and have your results in 20 minutes.

As NSW struggles to contain its current Delta outbreak, frontline workers in high-risk areas are undergoing regular testing with these rapid antigen kits too. The federal government says it’s now considering how the tests might fit into the national plan to reopen Australia, and some businesses are already offering them to staff. But scientists stress they are no substitute for the current “gold standard” PCR lab test.

So, how do these tests work and, with testing still a crucial part of our fight against COVID, will they become part of our daily lives?

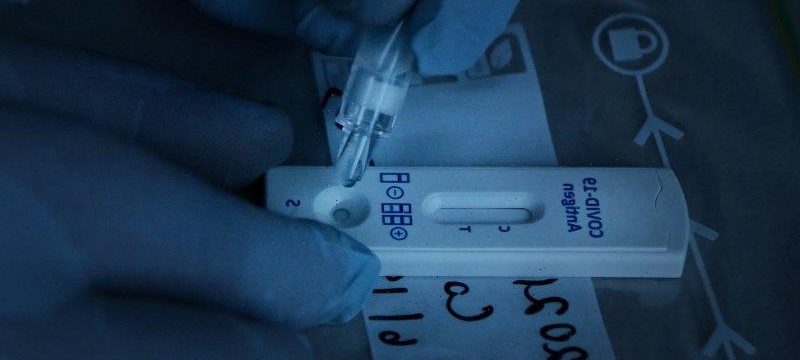

Australia has been slower than other nations to implement rapid antigen tests. Credit:Kate Geraghty

What are rapid antigen tests and how are they different from other tests?

The rapid antigen tests are not the finger-prick antibody tests you might have heard about early in the pandemic – those test our blood for the virus-killing proteins made by our immune system after it encounters the virus. They can take some time to show up so antibody tests are not good at picking up early infections (which is also when people are most infectious).

Instead, the antigen tests, as with PCR, test for the virus itself. Both tests involve collecting a sample from where we shed viral particles – the nose and mouth. But, as Professor Deborah Williamson, deputy director of the Microbiological Diagnostic Unit at the Doherty Institute explains, the rapid tests don’t need to go quite as far up the nose as the famously eye-watering PCR swab. “That’s known as the brain tickler,” she says, with the Q-tip inserted high up the nose and then the back of the throat.

These PCR tests amplify their sample in the lab to see if it matches the coronavirus’s genetic code (PCR stands for polymerase chain reaction, the lab technique that spins up DNA). The tiniest fragments of the virus can be found this way, even if it’s already dead. That makes PCR tests almost 100 per cent accurate, but it also means results are slower, taking many hours, and more expensive – about $100 per test compared to $5 to $30 for an antigen test (though PCR tests are free, covered by Medicare).

The rapids, meanwhile, are more like a pregnancy test, Williamson says. “Except obviously, it’s a, ahem, quite different bodily fluid being sampled.” They use a little chemistry set to test for a particular protein of the virus, known as an antigen, in your nasal swab by seeing if it reacts to a solution. The swab is generally placed in a dropper of solution to drip onto the paper of the test container for results. These typically take between 15 and 30 minutes to emerge (one line on the test means negative, two lines mean positive). Rapid results help health authorities isolate cases much earlier, cutting off the virus’s spread, and could lighten the load on PCR labs or improve COVID screening before flights and events. About 20 rapid antigen tests are already authorised for use in Australia by its medical regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) but you need training to use one; generally a registered healthcare worker will come in to perform them. Home testing kits, along the lines of those used in the UK, are banned.

How accurate are rapid antigen tests?

Because the rapid tests are not amplifying the viral sample, Williamson says, they are “inherently less sensitive than PCR”. At the tail end of Melbourne’s second wave in October, she ran a trial across the emergency departments of three major Melbourne hospitals. About 2500 people who needed a PCR test for COVID got an antigen test too, and the team could compare the results as well as the logistics of rolling them out. “People found the kits pretty easy to use,” she says. “And we did find the rapid tests were about as sensitive as the manufacturer had said. It found about 77 per cent of all cases in their [main] two-week infectious period. But it was more sensitive in the first seven days of symptoms.”

A review of similar trials around the world found that, when used as a one-off diagnostic tool in this way, antigen tests would pick up only between 40 and 74 per cent of cases without symptoms, and some brands better than others. That means a lot of cases will slip through the cracks as “false negatives”.

But, when the rapid tests are used frequently to screen the same people, say for testing frontline workers every few days, errors can be cancelled out, and their overall accuracy climbs back closer to PCR tests, which are harder to use continuously.

In August, the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia warned against the “uncontrolled use of rapid antigen tests” due to their sensitivity “limitations”, but acknowledged that states fighting outbreaks may need to use them for surveillance screening. Still, President Dr Michael Dray said the tests should never be used alone for diagnosis as any false negative “may provide unwarranted reassurance and lead to ongoing community transmission”. And he added: “It is wrong to automatically assume that mass surveillance through frequent use of [rapid tests] may detect … infection more (or as) quickly as infrequent use of the superior gold standard PCR.” While that strategy has “some rationale” in countries such as the US and the UK where the virus is everywhere, and PCR testing cannot keep up, Dray said not enough is known about how it would work in countries such as Australia and New Zealand with fewer cases.

Yet in a February letter in The Lancet, a group of senior researchers stressed that the main role of the rapid tests was to pick up cases while they were infectious with COVID and shedding a lot of virus. PCR tests will always be better for tracking down the asymptomatic cases. When paired with PCR, a major trial in the UK city of Liverpool found regular screening with the rapid tests helped flatten overall caseloads.

The Delta variant is twice as infectious as the original strain of the virus that emerged in Wuhan in late 2019, meaning the amount of virus people shed (viral load) is higher. “So tests like these might pick it up more often,” says Associate Professor David Anderson, a microbiologist at the Burnet Diagnostics Initiative. “When we first were trialling the different kinds of tests, the original strains didn’t have as much viral load to work with.”

Pathologists have been accused of running a testing cartel in their opposition to rapid tests, as they make money from running the PCR results, but Anderson and Williamson say there are good reasons to be cautious of antigen kits, and proper trials are needed in Australia. What works in the UK and the United States will not necessarily work here.

“The tests really have a lot of promise,” Anderson says. “They’re much better than the finger-prick antibody tests for finding infectious people. But we can’t just blindly spend millions [of dollars] rolling them out until we know more about how they’ll work best. The UK has spent hundreds of millions of pounds on them with very little coordination, and they still don’t really know whether they’ve helped [at scale].”

The federal Department of Health has begun trialling voluntary rapid antigen testing of aged care workers at two facilities in Sydney, which a spokeswoman said would expand to more than 50 providers over the next eight weeks.

“The department is currently considering the use of rapid antigen testing as part of Australia’s COVID-19 testing strategy and how this might fit into the national plan to transition Australia’s National COVID Response,” she said. As for supply of the tests, she said recent advice “from the majority of suppliers is that there is currently no major shortages”.

So will we be tested everywhere we go with these faster kits?

Probably not just yet. Scientists and health departments, including in NSW and Victoria, stress that rapid antigen tests cannot replace PCR, which will still be needed to confirm any positive results they throw up. And for symptomatic cases or those in quarantine where the risk of exposure is high, Anderson thinks PCR is still best. “But for parts of the world where there’s no way they’re ever going to be able to have the lab capacity to roll out hundreds of thousands of PCR tests daily like we do, these are a good option.” In late 2020, the World Health Organisation began rolling out millions of tests to the developing world which has struggled to access testing equipment just as it has struggled to access vaccines hoarded by wealthier nations.

In countries such as France and the US with high caseloads, antigen testing has helped take the load off PCR labs. “And it could for us too,” Anderson says. “But it’s really for when our vaccination rates are up higher, say at 80 per cent, then we can afford to miss more cases and accept more risk.”

Williamson agrees. Countries such as Germany have made accessing much of everyday life, from gyms to dining out, conditional on passing a rapid test. But she says, “although it’s really conceptually attractive to think you could have a one-off rapid test right before you go to the footy or hit the town, this kind of test works better for ongoing screening”. “People see the gulf between what we’re doing here in Australia and what [some countries] overseas are doing with these tests. And yes, the TGA has put in place a very strong regulatory framework around testing but that’s served us well.”

Still, she notes that how we use the tests will also depend on how much virus is loose in the community. “As we transition through the pandemic and we start to think about opening up, there are very real questions of whether that PCR capacity will still meet demand for testing, it seems unlikely it will. So last year rapid antigen tests weren’t thought to have a role [because] they’re not as accurate and we had PCR capacity and low cases but now is the time to trial them and see how they might fit in.”

NSW is planning to use the tests to help students return to school, something that has been trialled in the UK and elsewhere. “But the only real way we will know how it will work here is if we do proper studies too,” Williamson says.

Many businesses will inevitably adopt staff screening using the rapid tests, she adds. “But a lot of the onus will be on those workplaces.”

The TGA has now released guidelines for businesses bringing in the tests and a NSW Health spokeswoman said it was expected that workplaces would secure and cover the cost of TGA-approved testing kits.

“If you’re screening workers every three days, for example, you’ll still miss people,” Anderson warns. “Even NSW’s [rapid testing of frontline workers] in high-risk areas doesn’t make sense, we know there are cases outside those areas too. But screening is a worthwhile thing to do if we don’t have the capacity for PCR. People stacking shelves at the supermarket at two in the morning away from everyone probably aren’t the ones I’d target. But people working in say aged care, oh yes.”

Already some people are required to return a negative PCR test a few days before certain activities, such as boarding a plane. But, because of the delay in PCR testing turnaround, a new infection can take hold in that window. “Really, PCR testing, if it takes more than a day to come back, it’s not working,” Anderson says. That’s why some experts have suggested an extra layer of rapid testing on-site at the airport or concert line will cut down spread even further. But Anderson doesn’t see long queues to get tested before a live show or the footy as the answer “because some cases will still get through, and then you think everyone around you is safe, you’ve let your guard down. But a one-off test at the MCG is still different to, say, a school because there you could have repeated screening.”

As for home testing, it’s already banned for most illnesses in Australia, Williamson says, though there are some exceptions such as at-home finger-prick antibody tests for HIV.

Even if the TGA was to drop its ban on self-testing at home for COVID, Anderson expects it would be a logistical nightmare. “Not only would you get the false sense of security again but the tests really are better when they’re done by someone who’s trained and people can do it wrong or lie. Anecdotally, we’re already hearing of some people trying to game the system in the UK, giving the test to someone else to do so they can go to work or even stay home and fake sick.”

He agrees with experts who want Australia to develop a national framework on how best to roll out antigen testing. “The TGA says how they can be used, not how they should be used.”

Meanwhile, new tests using the fast gene-editing tool CRISPR have even been developed in the US, but Anderson says that, on cost and logistics, they don’t seem likely to be game-changers either.

We can’t rely on testing and screening alone, he says, just as the national vaccination coverage targets for reopening themselves rely on ongoing testing and quarantine remaining in force. “It’s a combination, it will be vaccines and other public health measures like masks that keep us safe for some time yet.”

Williamson agrees that rapid tests are one more tool in the pandemic toolkit, but do not alone offer a clear road back to reopening.

“PCR, for example, still has a major role to play,” she says. “Our lab workers have been working around the clock to produce these test results so far, they’re really the engine room of the entire public health response.”

If you'd like some expert background on an issue or a news event, drop us a line at [email protected] or [email protected]. Read more explainers here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article