Like all American Jews, I grew up in the long shadow of the Holocaust.

When Representative Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez referred to the US government-run migrant detention facilities as “concentration camps” on Instagram in June 2019, I had a visceral reaction.

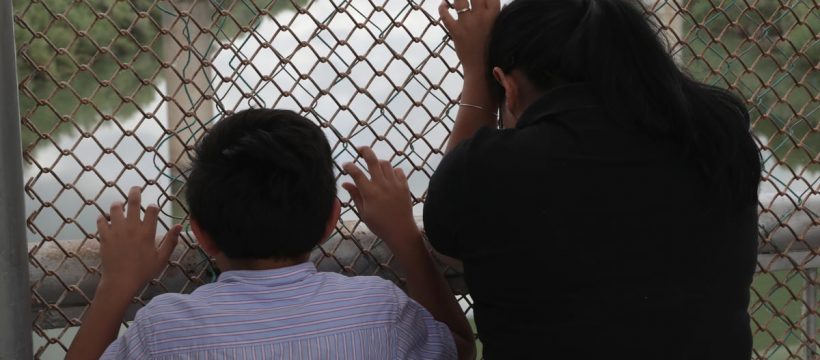

Nicaraguan asylum seekers await processing by the United States.

When Vice President Mike Pence chastised her for “cheapen[ing]” the Holocaust, I had an even more visceral reaction.

When I saw major Jewish organizations I deeply respect and admire, like the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, criticizing her — and being criticized in turn — I was nearly apoplectic.

I was angry at everyone.

Let’s get one thing straight before we start: what is happening to migrants on the southern US border is horrific, counterproductive, and inhumane.

Let’s also get another thing straight: this is not the first time the American government has led or sanctioned mass internment of civilians, or the separation of children from their families. For hundreds of years, slave markets permanently and legally separated families with no care or recourse. Starting in the 19th century, Native American children were forcibly removed from families and put in boarding schools for forced assimilation. As a child, I grew up about three miles south of the Sacramento bus stop where thousands of Japanese-Americans were rounded up and sent to internment camps throughout the West Coast. Our outrage is warranted, but this crisis is not unprecedented.

The US government is currently detaining more than 90,000 migrants. Many of these people (because, despite attempts to dehumanize them, they are, in fact, people) are now held in indefinite detention across over 200 facilities run by Custom and Border Patrol (CBP), Immigrant and Customs Enforcement (ICE), or the Department of Health and Human Services (DHS). These facilities are unsanitary and overcrowded. Thousands have reported sexual assault while in detention. Twenty-four have died.

In a CNN poll, nearly 75 percent of Americans now believe this situation is an immigration crisis, but there is sharp disagreement over what kind — and herein lies a problem.

When asked what kind of crisis this is, respondents split, with 54 percent of Democrats defining the crisis as the treatment of migrants, while 63 percent of Republicans define the issue as the sheer volume of these migrants in the first place.

This underscores the imperfections of language, especially in this context. In the poll, 74 percent of people agree on the wording (“crisis at the border”), though they do not actually agree on what those words mean. They are talking past each other.

I believe a similar phenomenon is happening around the use of the phrase “concentration camp.”

Here’s something you may not know about the cultural experience of being Jewish in America: we (I speak in generalities, but of course, only for myself) are taught from a young age to stay vigilant, to remember the past. We’re taught that anti-Semitism is everywhere, even if it’s behind closed doors or concealed within a forced smile. Some of the most vivid memories tied to my religious identity are of violence, the threat of violence, or paranoia around the threat of violence.

Most of all, we’re taught that the Holocaust could happen again.

When I was younger, I fought against this mentality. I was in America; I was free.

The recent past has forced me to accept the wisdom of my parent’s and grandparents’ generations. Vigilance is smart, not old-fashioned. Twelve people have been killed in synagogues since my last birthday.

But what, I must ask myself, is this vigilance for, if not to prevent atrocities against all people, not just Jews?

Here is where I think many people stop having the same conversation.

The phrase “concentration camp” has a general meaning, but that is not what I (and I expect many Jews) hear when the words are used.

Waitman Wade Beorn, Holocaust and genocide studies historian at the University of Virginia, says concentration camps are “designed — at the most basic level — to separate one group of people from another group. Usually, because the majority group, or the creators of the camp, deem the people they’re putting in it to be dangerous or undesirable in some way.”

Defined this way, we have seen many, many examples of concentration camps in human and American history. Certainly, the definition includes the current mass detention of migrants.

What we have not seen in the recent past, indeed what makes the horrors of World War II beyond compare, are state-sanctioned death or extermination camps. (The exception I will offer is the current detention and mass murder of Uyghur Muslims in China, which you can read about here).

The purpose of many Nazi concentration camps was not to corral Jews while they were processed through a bureaucratic government before being deported. It was not to deter additional Jews from entering Germany. It was systematic genocide. This is different. This was not merely inhumane; it was inhuman.

I’ve realized that my visceral reaction to the use of “concentration camp” is tied to its use as a rhetorical device. I believe that Representative Ocasio-Cortez used the phrase not because she believed the situations are equal, but to shock people by establishing a comparison so horrifying that we would be compelled to act.

And here’s the thing: I do not disagree with her that we must act to support the humane and just treatment of migrants. I do, however, disagree with using the Holocaust as a proverbial measuring stick by which to grade all other atrocities.

Here’s the thing: I believe the treatment of migrants can be utterly horrific in its own right, without requiring validation by a direct comparison to the Holocaust.

I have to question, though, if perhaps this is because as a Jewish person, I have been internalizing the lessons of the Holocaust — and the possibility of it happening again — my entire life.

I have learned to look for signs of dehumanization or criminalization of existence (something I have come to realize the black community faces in America still today). I have learned to identify politicians willing to co-opt human frailty for political expediency or gain. I have learned to be vigilant.

Now I must ask myself: if using the term “concentration camp” helps others to do the same, is this not a good thing?

Perhaps for others, the intensity of the proverbial comparison is what they needed to wake up. Perhaps it was necessary to ensure the memory of the Holocaust can be used to teach, inform, and prevent human rights abuses, even in markedly different contexts.

I am still angry, but asking myself why has proved fruitful. I do believe that migrant detention facilities fit the definition of “concentration camps,” though I also believe this comparison lacks nuance and does nothing to address the disparate experience of language across communities.

More than anything, I believe the Jewish community has a right to protect and safeguard the memory of the Holocaust, but only insofar as this memory may push us — as humans — to a better and safer world for all.

If use of the term “concentration camps” will get us there, then so be it.

Source: Read Full Article