My fight with Keith Moon, a naked Larry Hagman and how I wrote smash-hit film That’ll Be The Day on a shoestring, writes RAY CONNOLLY

No one sets out to write a film that half a century later is considered a cult movie. But I did, by accident, when, in 1972, I wrote a film called That’ll Be The Day.

I watched it go from being a story about a sixth-form boy who drops out of school to work at a fairground — culminating in a sweet romance on a roller-skating rink — to a blockbuster movie packing cinemas, a number one album, a gold record and a bestselling paperback.

Looking back, I can see that the success of That’ll Be The Day — released 50 years ago in April — was largely due to a series of random and lucky connections. Perhaps that’s the way with lots of success stories.

I’d always been a film fan, but, although I’d reviewed some movies for the London Evening Standard, where I mainly interviewed rock stars and other cultural heroes, I’d never actually seen a screenplay. Then one Saturday in 1972, I went to a friend’s house to borrow a book. That was the first stroke of luck.

The friend was David Puttnam, who, after a career in advertising had recently become a film producer. I’d got to know him thanks to Mike McCartney, the brother of Paul, who reckoned that the two of us would get on very well.

We did, and, after handing me the book that I needed, David, out of nowhere, asked me to write a film for him and his business partner, Sandy Lieberson. He had an idea that had been triggered by the Harry Nilsson song, 1941.

I knew Nilsson and I knew the song. It tells the story of a boy of our war-baby generation, whose father had abandoned his wife and son. When the boy reaches his teens, he runs off to join a circus.

‘But what if our boy runs off to join a fair?’ David suggested. To both of us, fairgrounds had been the only place in our teens where we could hear rock music played LOUD, the way it was meant to be heard.

At the same time, fairs suggested a dangerous glamour that was at odds with the ambitious lives our parents wanted for us.

‘Qualifications,’ was probably every parent’s mantra in the Fifties, but teenage rebellion was more romantic for a movie than qualifications could ever be.

So, that afternoon, over a cup of tea, David and I invented a clever grammar-school boy who, breaking all the rules, spurns the chance to go to university, and pursues a rake’s progress before he discovers his real path in life.

What we wanted was to capture the excitement of our own rites-of-passage years. We didn’t want to make a plucky Brits wartime film, or a kitchen sink, grim-up-north story, and absolutely not a larky ‘darling-we’re-the-young-ones’ holiday jaunt.

We wanted it to be real, about how our generation had been in that seemingly monochrome late Fifties period, just before the Sixties changed everything.

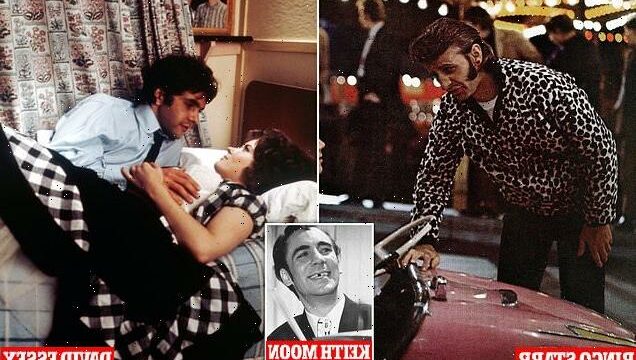

David Essex and Deborah Watling are pictured in ‘That’ll Be The Day’

Over the next few months, as I wrote my screenplay, I began to realise that no matter how wayward a lead character can be, he has to either have some wonderful redeeming grace or be devilishly good-looking and loveable.

Unfortunately, the character I created, whom I called Jim MacLaine, was too real. With all the selfishness of a teenager, he hardly does one decent thing in the entire script.

Audiences might hate him, we worried. Then one night David took his children to see a West End show called Godspell. That was our second lucky break.

He rang me the next morning: ‘I think we’ve found our boy,’ he said. The young actor playing the lead in Godspell was David Essex, who was so winning and good-looking that a cinema audience would forgive him anything. When the film was shown, they did.

I’d never been to a Butlin’s holiday camp, where part of our story would take place, but I’d been told of lust in the chalets, when teenagers would often be away from home and parents for the first time.

And I knew that Ringo Starr had performed at one during his pre-Beatle days. So, for research purposes, and with half an idea that he might like to be in our holiday camp band, we arranged a lunch with Ringo and Neil Aspinall, who had once been the Beatles’ road manager but, by then, was the managing director of their Apple company.

He’d been to Butlin’s, too, and he and Ringo amused us so much that David Puttnam offered Ringo a part in our film, and Neil put together a group to play in it.

That was how Keith Moon and Jack Bruce of Cream, and the very shy Billy Fury, got in the film. More good luck.

What had started life as a story about a clever boy, who writes jokey poetry about Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV, and who chucks his books into a stream on the day he should be sitting A-level history, was becoming, by degrees, a rock ‘n’ roll film.

We’d always intended to have a few songs in our story, but, when it turned out that some of the financing depended on there being a double album of famous hit records, I rewrote sections of the screenplay to fit.

In that way we might hear 15 seconds of Sealed With A Kiss if the screen action is, for example, snogging on the big wheel, a smidgen of Runaround Sue when we cut to chasing girls on the dodgem cars and a fragment of Great Balls Of Fire by the time we reached the roller coaster.

One of my fondest memories of that time was sitting with David Puttnam, going through our Oldies But Goldies books and choosing our favourite records. That was how we arrived at the film’s title, That’ll Be The Day.

Keith Moon of The Who is pictured on set of ‘That’ll Be The Day’

Filming was mainly on the Isle of Wight, because we thought it still had a look of the 1950s. We went on the ferry, Keith Moon arrived in a helicopter, while Ringo turned up in a chauffeur-driven car, wearing the teddy boy outfit he’d had specially made for the Magical Mystery Tour launch party.

It was an inexpensive little shoot, with Robert Lindsay as Terry, Jim MacLaine’s earnest, goody-goody school pal. To be honest, I probably had more in common with Terry, who goes off to university, than the part David Essex played.

I got down to the set as often as possible, taking Sacha Puttnam, David’s five-year-old son, who played the young Jim MacLaine in the opening sequence; and writing an extra snooker hall scene for Ringo when, surprised at how good he was, we wanted more of him.

Interestingly, Ringo was happy to do the extra scene, but he was determined to catch the last ferry to Portsmouth, whether or not the scene was finished.

As I grabbed a lift with him back to London that night, I realised that while the film was the biggest thing in my career, Ringo had had bigger days.

When That’ll Be The Day was released in April 1973, the best I was hoping was that it wouldn’t be ridiculed, or just ignored by the critics. So, I was astonished when the majority of reviews were very good.

But only when the movie began playing to full houses around the country did the marketing strategy behind the 40-song That’ll Be The Day album become apparent, in that a TV commercial for the record showed clips from the film. The album topped the LP charts for weeks with virtually everyone we knew buying a copy. David and I both received gold celebratory records for it, too, although the only thing I’d done was to choose my favourite songs.

A That’ll Be The Day novella that I wrote based on my screenplay became a best-seller, too, and for months I got letters from O-level pupils who had chosen it as their favourite book. What I think they really wanted was for me to write their homework essays for them.

It was wonderful to have a hit with my first screenplay, but I didn’t like everything in the finished film, particularly one scene where David Essex’s character has sex with a young girl at the fair. My intention when writing it had been that the girl had been enjoying some heavy petting that had gone too far, which she’d immediately regretted.

Claude Whatham, the director, saw it differently and in the film it is a darker scene, something that has always made me uneasy.

The entire film only cost £210,000 to make, which was tiny — just over £1 million in today’s money — with all the principals being paid £5,000 (about £50,000 now). That was a fortune for me, but, I suspect, rather less of one for Ringo. I spent some of my money putting down a deposit on a big, classic, white Citroen DS. I wish I still had it.

Even before our film was released, David Puttnam was thinking about a sequel. This time, it would be the story of youthful Britain’s obsession with pop groups in the Sixties seen through the Jim MacLaine character. We called it Stardust, although the public probably thought of it as That’ll Be The Day 2.

David Essex hadn’t sung in the first film, but in the gap between the two movies, he’d become a teen idol with his record Rock On. So, we now had our very own rock star to play the leading part. What we didn’t get, however, was a Beatle, with Ringo declining to repeat his role.

Ringo Starr and David Essex are seen in ‘That’ll Be The Day’

Adam Faith got the part instead. Initially, I was dead set against him, and our new director Michael Apted wasn’t sure either. Most producers would have pulled rank and sent me back to my typewriter.

But David liked writers and dragged me to meet Adam, who immediately did to me what his character does to all those who stand in his way in the film. He slyly chatted me out of my doubts. We thought Tony Curtis was going to play the American rock manager, but when his Hollywood agent demanded a fee that was somewhere in the region of a third of the movie’s budget, Larry Hagman stepped in.

A few years later Larry would play JR Ewing in the TV series Dallas, and, when asked where he got the JR character from, he said that his performance had come from his role in Stardust.

It can’t have been easy for David Essex to play a rock star as his own rock fame was growing by the day. But it probably wasn’t easy for Keith Moon, either.

In The Who, Keith was used to fan adoration, but to us he was just another actor playing a small part and miming playing the drums which, actually, musician Dave Edmunds had pre-recorded. That wouldn’t have sat well with his ego.

Always desperate to be the centre of attention, Keith would be spotted walking naked around our hotel car park at three in the morning just when the crew was returning from a night shoot that hadn’t involved him. On another occasion he ‘borrowed’ the unit carpenter’s tool bag and sawed the door of his hotel room in half, so that he could hang his head out of it like a horse in a stable.

Very friendly, funny and likeable at one moment, he could be a real pest the next. And one night in Manchester he and I fell out, with him trying to hit me.

Naturally, I responded, whereupon a scrum of production assistants descended on the wrestling drummer and screenwriter. ‘Don’t hit his face,’ the make-up artist shouted to me. ‘He’s been made up.’

Presumably, blows to any other part of the drummer’s body that wouldn’t have shown on camera would have been fine. The following day, Keith and I were good friends again, the little spat forgotten.

Filming concluded in California, which is a long way from where our story had started on the Isle of Wight, and, after the last scene, Larry Hagman invited all the principals to his house in Malibu.

By now we’d got to know Larry and his wife pretty well, but we were astonished when after dinner they led us into a veranda where, without warning, they took off all their clothes, and, standing naked, invited us to get into their Jacuzzi with them.

Welcome to Hollywood.

When the film came out it was an even bigger hit, with a line I’d written for the album notes — ‘Show me a boy who never wanted to be a rock star and I’ll show you a liar’ — used on all the publicity and posters.

But, to be honest, of the two, I’ve always preferred the simple realism of That’ll Be The Day, which was about ordinary people in ordinary situations.

David and I worked very closely together on both films, so, I would have been happy to share the credits so each read ‘Story by Ray Connolly & David Puttnam’ and ‘Screenplay by Ray Connolly’. But David didn’t want it. He wanted to be a very famous film producer, which is exactly what he became, with films such as Chariots Of Fire and The Killing Fields.

Fifty years on we’re still friends, enjoying remembering that cup of tea on the day That’ll Be The Day was conceived.

- Ray Connolly’s novella, Sorry, Boys, You Failed The Audition, is available on Amazon.

Source: Read Full Article