It’s mid-summer. Normally we’d be covering the openings of “The Forever Purge” and “Ghostbusters: Afterlife,” with “Minions: Rise of Gru” in its second weekend competing for #1. As usual, all franchise titles, likely all hits.

Thirty-three years ago on the same weekend, another “franchise” was #2. His name was Stanley Kubrick, and “Full Metal Jacket,” his 12th film, went wide and began its successful road to profit.

The master filmmaker’s first release in seven years, “Jacket” continued his fruitful exclusive relationship with Warner Bros. (similar to the studio’s ties with Clint Eastwood and Christopher Nolan). Atypically for the season and the studio, it started as a limited release on June 26, then expanded on July 10. 12 years later his posthumously released “Eyes Wide Shut” opened on July 16. It’s impossible imagining either going in summer or even being made.

Kubrick’s ability to make such esoteric films didn’t happen in a vacuum. It was related to his establishing himself as a lucrative source of both profit and prestige for studios. The final nine of his 13 features all scored domestic grosses of $90 million (adjusted) or better, and all but his first three made money despite usually carrying elevated expense based on the director’s rigorous production demands.

Here is how his films worked in the U.S./Canada, in order of their gross (all adjusted as are budgets to 2020 values — the numbers are inexact but close):

Popular on IndieWire

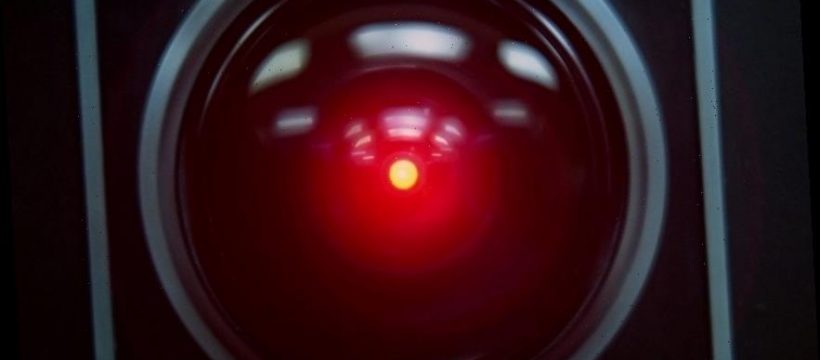

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968/MGM) – Gross: $410 million; Budget: $88 million

Kubrick’s best known and most acclaimed film (#6 on the most recent Sight & Sound greatest films of all time critics’ survey) actually lost money on initial release, with its then-massive budget and polarized critical reaction (mixed to negative from Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, the New York Times, Variety, John Simon) limiting its initial appeal. This extended to awards, where it was ignored by critics’ groups and won only for Special Effects among its four Oscar nominations (snubbed for Best Picture).

But as perhaps along with “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” (gross almost entirely from midnight shows, over $100 million higher) the most sustained cult interest film ever, “2001” continued to add to its revenue in 1969, then reissues and consistent library have now made it also his biggest hit.

MGM placed this as a road show release. The strategy, mostly used for top musicals and historical epics (“The Sound of Music,” “Ben-Hur”) meant it played exclusively in big cities for months at elevated ticket prices and limited shows, with a slower release pattern continuing as it expanded. Most early dates were in 70mm and Cinerama, with the visual experience (quickly recommended to be viewed while high) a big draw.

Whatever its initial slow financial return, this built on Kubrick’s already major reputation and set him up for creative freedom with Warner Bros. starting with “A Clockwork Orange.”

2. Spartacus (1960/Universal) – Gross: $366 million; Budget: $105 million

Kubrick’s sole film for which he had no development role (he was brought in to direct a week into filming by producer/star Kirk Douglas) was the #1 domestic release for 1960 (though “Psycho” ultimately overtook it), and until 1970, its studio’s biggest hit. It followed in the wake of the massive “Ben-Hur,” and replicated its road show release. Though Kubrick disowned the film as not his vision, it remains, because of Douglas’ stirring portrayal, at the high end of the director’s still popular works.

“The Shining”

Warner Bros.

3. The Shining (1980/Warner Bros.) – Gross: $153 million; Budget: $59 million

The fourth biggest film in its summer, this Stephen King adaptation owed its success more than most Kubrick hits to its star. Jack Nicholson’s bravura performance caught the public’s fancy as much as Kubrick’s distinctive design for the Overlook Hotel in this horror-genre film.

Made in search of a hit after his more lackluster “Barry Lyndon” results, it is no less cerebral than most of his films, but its distinctive scares appealed to a more general audience than most of his films.

Warners tread carefully with the unconventional film, opening limited in late May before expanding weeks later. It never was a #1 film, but consistently held well as audiences rather than critics responded well to it (among its negative reviews: Pauline Kael, Ebert and Siskel, The New York Times). 40 years later, it is likely the most widely known film of 1980 other than “The Empire Strikes Back.”

4. A Clockwork Orange (1971/Warner Bros.) – Gross: $140 million; Budget: $15 million

A massive hit compared to its cost, this initially X-rated dystopian nihilistic commentary on juvenile violence benefited from its year-end release (in New York and Los Angeles; other U.S. cities rolled out in January). It won best film from the New York Film Critics Circle (though Kael and others dissented) and became one of Kubrick’s three Best Picture nominees at the Oscars.

Warners for its initial Kubrick release exerted a careful strategic release with initial reserved performances (a variation on road shows without seat selection but limited show times). Though WB personnel changed, it set the tone at the company for treating his films as important as any they released. In this case, combined with its awards haul, it elevated what might have been just a sensationalized release into a genuine event.

5. Full Metal Jacket (1987/Warner Bros.) – Gross: $108 million; Budget: $70 million

The expense of recreating Vietnamese exteriors and an American base camp in England (where Kubrick made all of his films after “Spartacus”) cut into the profits of this. It benefited from strong foreign grosses and the best overall reviews ahead of its initial release than any of his films since “Dr. Strangelove.” And there was the usual appetite for a war film irrespective of its esoteric vision. It lacked any stars to draw, adding to all the other aspects that make it impossible to envision today.

Warners again was careful, opening in limited release at the end of June. It expanded on July 10 to under 1,000 theaters (fewer than any other top ten release that week), then held better than most other titles in the following weeks. It hasn’t sustained public interest as much as earlier titles.

6. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964/Columbia) – Gross: $103 million; Budget: $15 million

Though not quite making it into the top ten for 1964, this was a major hit at the time before attaining legendary status among comedies. It overcame a major release date issue. Originally planned for December, 1963, President Kennedy’s death caused cold feet. Its acclaim the next year — including best film from the New York Film Critics and multiple Oscar nominations despite a January release (the same month the Beatles first broke out in the U.S.) suggest that had it kept its original date it might have overtaken “Tom Jones” to win the 1963 awards.

The response followed the pattern of art-house films, some of which like “La Dolce Vita” and other foreign smashes drove significant box-office by reaching an educated/upscale audience. Its humor represented the caustic, pointed attitude of current-event comedy styles then popular, from Nichols and May, Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, to Vaughn Meader. In any event, it remains timely and a classic after connecting from the start.

7. Lolita (1962/MGM) – Gross: $102 million; Budget: $18 million

Speaking of impossible to imagine easily today, even if there’s more innuendo here than explicitness, is “Lolita,” the content parameters of which were still dictated by the Production Code. Nakobov’s novel about a middle-aged professor’s obsession with a 14-year-old (two years older than the book) had been a bestseller after international bans. A daring project for a 33-year-old director on the rise.

With European films expanding boundaries, the climate was right for “Lolita.” It further elevated an already distinctive young director. Though it was well reviewed, it has not managed to remain among his best remembered films.

8. Eyes Wide Shut (1999/Warner Bros.) – Gross: $101 million; Budget: $118 million

Kubrick’s last film, 12 years after “Full Metal Jacket,” was his most driven by star-power, his most expensive, and the one after his initial low-budget films in the 1950s for which it was most challenging to make a profit. A much better foreign result looks to have gotten it there. (Ironically without adjusting any of the other titles for inflation, this is his top grossing film worldwide).

Of note‚ this was the only film in his entire career to initially receive a wide release. It opened mid-summer at #1, but fell quickly, only lasting three weeks in the Top Ten.

This was a Kubrick film in extremis — a 15-month shoot, most of it without a break, complete mystery about the plot other than the novel it was loosely based on, with a reliance on his name to draw interest as much as the Cruise/Kidman combination. But where “The Shining” felt like a normal extension of Jack Nicholson, the casting here didn’t have as much appeal. And times had changed. The peculiar worlds Kubrick created by 1999 were far removed from mass-audience film interest. By this point, reviews were critical and they were decidedly mixed and mostly unenthusiastic. But its reputation has continued to grow, and it has since gone on to top multiple “Best of the 1990s” film lists.

“Barry Lyndon”

9. Barry Lyndon (1975/Warner Bros.) – Gross: $91 million; Budget: $55 million

Again, the international box office saved this expensive (though probably only a fraction of a typical blockbuster’s budget in today’s production world) Thackeray adaptation. Kubrick’s biggest Oscar winner (four awards, also nominated for Picture and Director). It opened limited in December to qualify, built on its nominations, and had it not been so costly would have felt more like a success.

Its reputation has soared — it was the second highest ranked Kubrick film in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics’ poll, and the same for directors, who placed it very high at #19 on their own list.

10. Paths of Glory (1957/United Artists) – Gross: (est.) $18 million; Budget: $8 million

Kubrick’s leap forward after three low-budget films came after the acclaimed, though not widely seen, “The Killing.” Kirk Douglas signed on as the lead in this World War I troop mutiny drama that still stands as one of the most acclaimed anti-war films ever. It didn’t reach the hoped-for audience or awards attention its year-end release desired, but was awarded prestige status both for its themes and a distinctive creativity that set Kubrick up the rest of his career.

11. The Killing (1956/United Artists) – Gross: (est.) $3 million; Budget: $3 million

Even before “Paths,” this was the film that got Kubrick needed attention. The film noir, co-written by Jim Thompson with Sterling Hayden, received most of its bookings on a double feature with the Western “Bandido” and lost money initially. But against the odds it got enough critical attention to attract the studio interest that led to “Paths.”

12. Killer’s Kiss (1955/United Artists) – Gross: (est.) $1 million; Budget: $750,000

This 67-minute New York-filmed story of a young boxer and his obsession with a sexy neighbor was bought by UA for a little over its cost. It was released mainly as a second feature to minor notice until Kubrick became better known.

13. Fear and Desire (1953/Joseph Burstyn) – Gross (est.) $500,000; Budget: $500,000

Wishing to move beyond his successful career as a photographer for Look Magazine and with two short films to his credit, Kubrick made this self-financed bare-bones unnamed war-set film with a cast and crew of only 15. It was acquired by the leading art-house distributor of the time, Joseph Burstyn. He promoted it as an exploitation release to little notice. The limited prints were mostly lost, Kubrick allegedly destroyed the negative, and it remained unseen until the 1990s when the by-then public domain film was located. When shown at Telluride and then Film Forum, Kubrick asked that people not see it.

That’s only 13 films for one of the most iconic careers any director has had. Not unusual today, but for the last half of the 20th Century that’s a very spartan output. But it was a career that at its essence existed because of box office success, which for the most part exceeded his critical acclaim case by case. And along with his distributors, Kubrick deserves attention for his producing and marketing instincts that were crucial to his work getting attention every step of the way.

Sign Up: Stay on top of the latest breaking film and TV news! Sign up for our Email Newsletters here.

Source: Read Full Article