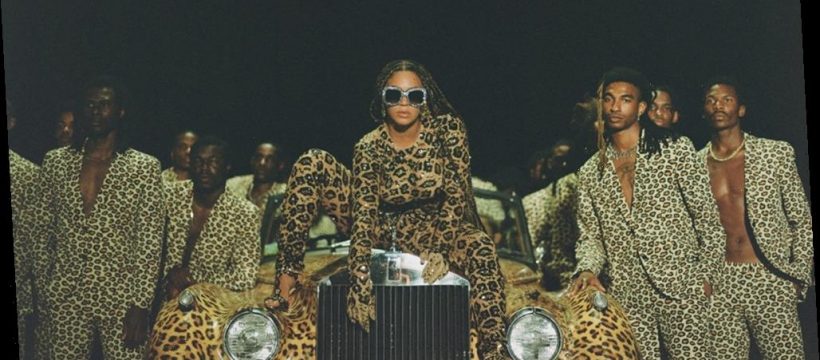

When Beyoncé Knowles-Carter announced her latest visual album “Black is King” in June, she explained that the Disney Plus film was “meant to celebrate the breadth and beauty of Black ancestry.”

“The events of 2020 have made the film’s vision and message even more relevant, as people across the world embark on a historic journey. … I believe that when Black people tell our own stories, we can shift the axis of the world and tell our REAL history of generational wealth and richness of soul that are not told in our history books,” Knowles-Carter wrote on social media.

The 24-time Grammy winner created the visual album to accompany “The Gift,” the soundtrack she curated for 2019’s “The Lion King.” Knowles-Carter voiced the adult version of lioness Nala in the photo-real adaptation of the animated classic.

But upon release of the film’s trailer in July, Knowles-Carter faced early criticism, particularly from Africans living on the continent, about how Africa would be portrayed. Among the concerns was whether or not “Black is King” would fall into old tropes of the continent being an undeveloped rural paradise with wide-open spaces rather than the bustling, modern place brimming with diverse cultures that it is.

Now that the film has been released internationally (it debuted last Friday), pop culture enthusiasts, experts and academics are weighing in — and unpacking the latest chapter in Beyoncé’s professional (and, it seems, personal) evolution.

“If ‘Lemonade’ is about all things African American, then ‘Black is King’ is about all things African,” says Oneka LaBennett, an associate professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. “But it’s also about Pan-Africanism — this wonderful celebration of the African diaspora that’s grounded in the continent.” She adds that the film is a dedication to not only Knowles-Carter’s own children (particularly 3-year-old son Sir), but all children of African descent.

LaBennett is the author of an extensive cultural study of Knowles-Carter’s visual album “Lemonade.” She says that “Black Is King” is a natural evolution from the artist, who has celebrated her Blackness in her music, lyrics and videos since her early days as a member of Destiny’s Child. What started as an experience largely rooted in the Black experience of the American South has now transitioned into something much broader, she says.

“[I] think that we can look at her more contemporary evolution, after Beyoncé comes out as a feminist, after Beyoncé called out her husband on adultery, there is a Black womanhood that she is now presenting to us full throttle,” LaBenett notes, adding that “Black is King” also touches on Beyoncé’s political activism, amid the groundswell of support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

“One of the most important elements of ‘Lemonade,’ was that she featured the mothers of the movement, that she had the little Black boy dancing in front of the police in riot gear,” LaBenett says. “And that was a clear reference to the Black Lives Matter movement, to the efforts in the struggle against police violence. I think in this work as well, she’s able to show political support for Black men [and also] elevate and celebrate Black women. She sees those as sort of intertwined efforts.”

Student-writer Nicolas Nhalungo and Africa No Filter executive director Moky Makura were among those who contextualized the criticism Knowles-Carter received when the first “Black Is King” trailers were released. After viewing, Makura says that while she thinks Beyoncé leaned into some stereotypes about the continent, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“The challenge with a stereotype is that stereotypes are true; they’re not stereotypes because they aren’t true,” says Makura, whose organization collaborates with African artists, journalists and new media leaders to craft their own stories, outside of Western media. “I think what we have always been concerned about are the filters, lenses — which story are we choosing to tell about the continent because Africa is a multiplicity of stories. If there is one thing that most people know, it’s the dances, it’s chalk on our faces, it’s the open spaces. … So, our thing was, ‘Are you telling the other side?’ I think she did.”

Makura emphasizes that Knowles-Carter was not telling “the story of Africa” through “Black Is King,” but rather a singular, stylized narrative which leveraged and included African artists.

“It was Beyoncé ‘s vision,” says Makura, who is Nigerian and based in South Africa. “It was her perspective of a story that she wanted to tell. The one thing I’ve been very clear about is that Beyoncé is not a journalist. She’s not reporting hard facts. She’s an artist. She’s a creative, so she’s putting together a creative vision of what she thinks the story is like, and that’s what you can see.”

“Was it visually appealing?” Makura asks. “Absolutely, yes, it was. Did it put Africa on the global agenda in terms of a Beyoncé audience? Absolutely, yes. Did you get people debating about whether or not it’s the ‘right Africa,’ if it’s a ‘negative Africa,’ it’s a stereotypical Africa? Absolutely. Is that good for the continent? Absolutely.”

Before watching “Black is King,” Nhalungo wrote a think piece centered on the initial criticisms, which questioned whether or not the artist was appropriating African cultures. Ultimately, Nhalungo, who is Mozambican, was impressed by Knowles-Carter’s attention to detail in creating the project.

“We can see that [she] really did her homework, and that she really took the time to research the history and the culture,” he says. “It’s true that Africa is a big continent with a lot of different complexity. It’s not easy to encapsulate that all into one thing, but she was able to do that. There are different details and she was so meticulous about it — the art, the fashion, the colors. It was very out-of-this-world.”

Nhalungo also points to the importance of the star sharing her global platform with African artists hailing from countries across the continent, including South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Guyana and Malaya.

Makura notes “Black Is King” has the chance to inform how continental Africans — made up of 3,000 different ethnic groups and over 2,000 languages — understand their neighbors.

“A lot of Africans learn about each other, ironically, from Western artists,” Makura says. “Because South Africans are not getting stories about Kenya themselves, Nigerians are not getting stories about others. So, we are actually learning about ourselves from these things. So this [film] that Beyoncé put out — it’s going to inform us about ourselves. That’s the irony. That is why this work matters.”

She adds, “Really, it’s beyond Beyoncé, but Beyoncé has this global platform that helps us start re-educating ourselves, and the world, about what we’re capable of.”

Source: Read Full Article