Seven years after her baby died from vehicular heatstroke, Kristie Reeves still dedicates her life to preventing hot car fatalities.

“I miss everything about her,” Reeves said of her daughter, Sophia Rayne “Ray Ray” Cavaliero. “She was such a balanced child and I know that sounds weird for a 1-year-old, but her personality was so easy-going.

“She was so friendly and kind, such a good baby and fun,” the mom told ABC News. “She made it easy to be a first-time mommy.”

On May 25, 2011, Ray Ray’s father, Brett Cavaliero, drove to work with the baby in his back seat, not realizing until later that day that he never dropped her off at daycare.

When Ray Ray was found, it was too late. She was one of 33 children to die that year from a hot car fatality, according to the Department of Meteorology and Climate Science at San Jose State University.

Brett Cavaliero was not charged based on the evidence of the investigation.

Reeves said that the nightmare of losing her daughter feels like it was yesterday.

“Especially this time of year, every summer is particularly hard,” she said. “Some days are not so horrific, but the angel day, birthday, Mother’s Day are always difficult. I tend to take that time off for extra counseling, therapy, and meditation to live through it because it’s like it just happened.”

Today, Reeves is part of the Texas Heat Stroke Task Force and works with Safe Kids Worldwide and Kids and Cars to speak out on behalf of hot car safety. She also helps parents cope after they’ve experienced tragedies or near misses.

Reeves wants other parents to understand that unless precaution is taken, that “this too can happen to you.”

“Don’t think for one moment that only a monster would do this,” she said. “I get why people dismiss it. It’s easier as parents than to accept the truth that your memory can fail you in times of stress, in times of chaos. That’s terrifying that your own mind can fail you with something so precious, your bundle of joy.”

In 2016, Reeves shared her full story with ABC News. Then, she had described how she dedicated her life to raising awareness of child vehicular heatstroke through her organization, Ray Ray’s Pledge.

On September 1, 2015, “Ray Ray’s Law” was passed in Texas, which mandates hospitals across the state to educate new parents on the dangers of hot car-related accidents and deaths. Hospitals and birthing centers now hand out pamphlets and some distribute teddy bear key chains to mothers and fathers as a reminder that they’re not riding alone in the car.

Reeves said this education should be just as important as SIDS and postpartum depression.

“Not once was I ever told about this danger to child passenger safety,” she said. “If you had asked me the day before May 24 [2011], I would have assumed it was very bad parents and parents who used the car as a babysitter. In these times when these children are forgotten, the most common factor was a change in routine.

“Mine was a wrong turn and we overslept.”

Reeves said that a change in who drops off the child, change in traffic, a wrong turn, missing an exit, a medical appointment, running late or an unexpected phone call have disrupted a parent’s pattern and resulted in hot car tragedies like her own. Special events like church or family reunions when people leave their doors unlocked have resulted in children entering a vehicle and becoming trapped inside.

“Every example that I have ever given is from an actual hot car death — not what could happen, but what did happen to good parents,” she said.

To prevent tragedies, Reeves suggests parents use the acronym, ACT.

Avoid controllable distractions.

This includes all mobile and hands-free devices.

Create reminders.

Reeves creates free reminders with her smartphone by setting alarms and utilizing apps that send a confirmation that the child has been picked up or dropped off.

Take action.

Dial 9-1-1 if you see an unattended child in a vehicle because timing is crucial.

“These kids can die in under an hour,” Reeves said.

All parents should also take action by employing what she calls a “safety circle.”

Reeves and Brett Cavaliero — who now has 5-year-old twin girls — ensure they’re safely dropped at school or home by the person transporting them and also the school. If they are not in school, teachers call Reeves to make sure the children are in a safe place.

Reeves is urging parents to utilize alarm systems on their smartphones as safety nets, reminding that child vehicular heatstroke can pose a danger for anyone.

While apps and car seat sensors can serve as reminders, Janette Fennell, president and founder of KidsAndCars.org, stresses that parents should have additional layers of protection when trying to prevent hot car-related tragedies.

“When you talk about apps they are helpful, but we can’t think of them as foolproof because as we know, we get into dead cell areas,” Fennell told “GMA.” “Until we have reliable technology, these are what we have to do to make sure children do not die in hot cars.”

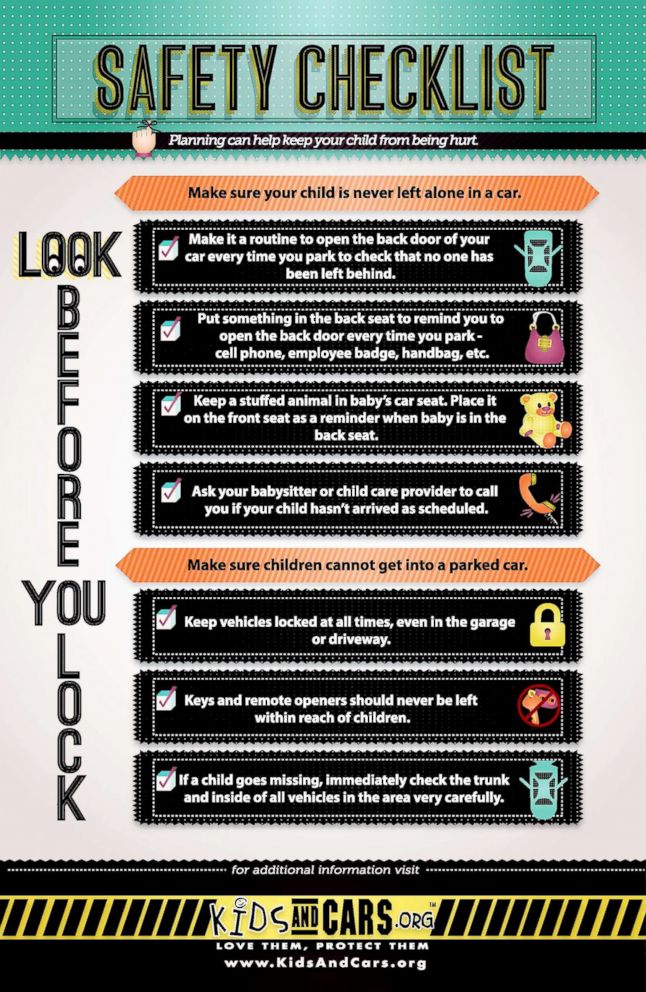

Fennell and KidsAndCars.org revealed the following safety checklist to prevent hot car tragedies.

Make sure your child is never left alone in a car.

1. Look before you lock: open the back door every time you park your car to ensure no one was left behind.

2. Put your cell phone, wallet, work badge or handbag in the backseat to remind you to open the back door each time you park.

3. Keep a stuffed animal in your baby’s car seat, then, place it on the front seat as a reminder when baby is in the back seat.

4. Ask your babysitter or daycare center to call you if your child hasn’t arrived as scheduled.

Make sure your child cannot get into a parked car.

1. Keep vehicles locked at all times, even in the garage or driveway.

2. Keys and remote openers should never be left within reach of children.

Fennell said that it’s crucial to keep your child from getting into the car, rather than teaching them how to get out. “Be sure your neighbors can lock their vehicles as well.

3. If a child goes missing, immediately check the trunk and inside your neighbor’s vehicles carefully.

“What we always say is that if there’s a body of water nearby, check that first,” Fennell said. “Then check all the nearby vehicles in the area and check the trunk.”

In 2017, the Hot Cars Act was introduced to Congress, which would direct the Department of Transportation to issue a final rule requiring all new passenger motor vehicles weighing less than 10,000 pounds be equipped with an auditory and visual system alerting the driver to check rear seats after their car is turned off.

The alert would be similar to that of a key-in-ignition alert, Fennell explained.

“If we only had a warning that a child was left in a vehicle, that can go a long way to prevent [hot car tragedies] from happening,” she noted.

Reeves said she supports the Hot Cars Act, 100 percent.

“Since the first year, which was 1998 when the law became rampant to move the kids to the back seat, we now have forgotten babies,” Reeves explained. “Every sensor in the front seat detects weight. That technology already exists. So why don’t we have the same alert systems in all back seats? Why are we stalling?”

In 2017, General Motor’s rolled out its Rear Seat Reminder System in some of its cars. The feature uses back door sensors that become activated when either the rear door is opened or closed within 10 minutes of the vehicle being started, or while the vehicle is running. Under these circumstances, when you reach your destination a reminder appears on the dashboard as well as an audible chime notification.

Last year, “Good Morning America” tested GM’s Rear Seat Reminder System along with three other technologies designed to prevent hot car deaths.

Also in 2017, Hyundai Motor Company announced it installed rear-occupant alert technology and Nissan USA revealed rear door alert technology, which is standard on the 2018 Pathfinder.

“The biggest mistake anyone can make is thinking that this can’t happen to them or anyone in their family,” Fennell said. “We must admit and understand that this can, and does happen to the very best people.”

ABC News’ Sarah Messer contributed to this report.

(Editor’s note: This article was originally published on June 7, 2018)

Source: Read Full Article