The murder of British MP Sir David Amess while holding routine meetings with voters shouldn’t be dismissed as a problem unique to the other side of the world. We must not fool ourselves. It could easily happen here too.

Over the past decade, the tone of the public debate has fallen so far that most federal MPs and senators will readily concede they think it’s a matter of when, not if, a similar incident occurs here.

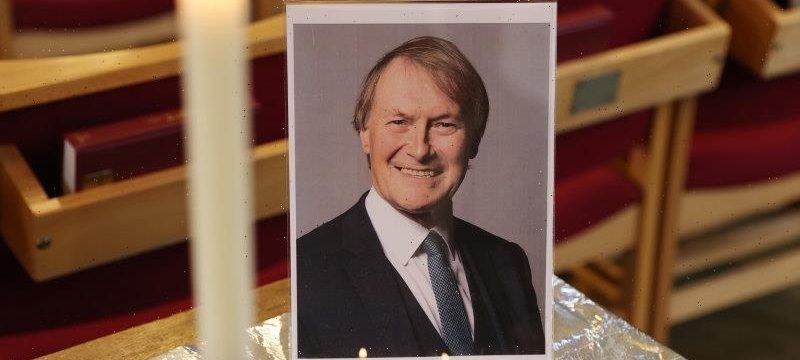

A portrait of English MP David Amess ahead of his funeral. He was stabbed to death during a constituency meeting. Credit:Getty

And a key factor in this? The erosion of the boundary between public and private life.

There is no longer a distinction between places of work, public events, private homes or personal time. Nor between elected officials and family members. Partisan media commentators don’t have a problem with publishing the personal phone numbers of MPs they don’t like on social media.

Worse, when politicians are “egged”, the perpetrator is often held up by their critics as a hero.

Protesters at the weekend in Darwin chanted the home address of the Northern Territory’s Chief Minister, adding: “Let’s go get the dog”.

Gradually these things have been normalised to the extent that the next act has to be more outrageous.

The weekend’s events in Britain follow a disturbing trend in that country and the United States. And it was sobering for many Australian MPs who fear it soon could be exported to our shores.

Not long ago, a federal cabinet minister was in Bunnings alongside their child on a Saturday afternoon, wearing shorts and a cap, when a QAnon adherent accosted them in the aisle and abused them about mandatory vaccinations in a “very aggressive” fashion. The harasser filmed the interaction, presumably intending to post it online. Fortunately for this MP they were one of the growing numbers who have, or have had, a 24-hour personal security detail.

Some ministers and even backbenchers have forked out tens of thousands of dollars of their own money to upgrade their homes. Higher brick walls, cameras, security lighting. Not just to ensure their safety at home but to ensure their family’s safety when everyone knows the MP is away.

A few share stories in private about detailed threats so appalling that they don’t want their partners or children to know.

In the past few years aggressive and violent incidents involving federal MPs have caused a spike in referrals to national security agencies. Men and women, on the left and on the right. Some threats are religiously motivated and some ideologically.

Coalition, Labor and Greens women have all had to contend with stalkers and rape threats.

There are federal MPs who refer direct threats on their lives to the Australian Federal Police at least monthly and federal police are now providing risk assessments for a growing number of elected representatives ahead of public appearances.

It is all at a huge cost to the taxpayer, which strains the AFP’s already limited resources. And so the idea of giving all MPs round-the-clock protection is not only regarded as unfeasible but impractical.

Josh Frydenberg last year become the first Australian Treasurer in history to be issued with a full-time security detail after he received threats to his safety in light of the coronavirus crisis.

In February, Labor frontbencher Madeleine King asked for an independent review into the workplace culture of parliament to be expanded to also look at the threats facing MPs and their staff from members of the public.

King, based in Perth, took out a restraining order against a man who had repeatedly turned up to her office and abused staff for more than a year. She told this masthead that the Department of Finance was “unable to assist” and it had not provided “adequate support when people are threatened and frightened”.

“Whilst we can ring the AFP, the local police, the ongoing resolution of these matters is just not addressed. It’s up to the MP alone… there’s no help from the parliament. In any other workplace, you could expect to be able to phone someone and get help,” she said at the time.

In 2019 her West Australian colleague, Anne Aly, and her staff were left shaken when a man entered her electorate office with a “fairly large kitchen knife”. She said the growing number of public incidents were alarming and aggressive taunts had moved “from social media to reality”.

Yet, some MPs must also take responsibility for pandering to the fringes of society, refusing to call out violent acts and, worse than that, actively whipping them up into a frenzy. And indeed the media must also bear some responsibility for the decline in public discourse.

Australian voters have the right to see their MPs and MPs want to interact with voters. But many will now tell you they no longer promote so-called mobile offices on social media when they visit towns within their electorates.

And if these events, where a voter can meet their MP and raise a concern without booking an appointment, fall away then we are all worse off.

Too often it takes a terrible event for people to reflect how we got here in the first place. Regular reminders about agreeing better, or making Parliament a “kinder, gentler” place are too often forgotten.

Let this be a reminder democracy is precious and must be protected at all costs.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article