Her own mother raised a family of eight long before children’s ‘rights’ or helicopter parenting existed. Now, in an enchanting memoir, top author EMMA DONOGHUE recalls the joyous 1950s diaries of family life that taught her how to be a mother

Some of the notebooks can fit in my palm, others are A4 size. My mother Frances started keeping a diary in 1948, when she was on the brink of becoming one of Aer Lingus’s first generations of flight attendants. She kept at it every day, even while she raised eight children.

The diaries were never a secret, or locked away; they sat on a shelf in plain sight. My siblings and I were free to try to decipher her scrawl, but we almost never did, except to look up the year of our own birth and find how she’d recorded our arrival: ‘New baby 6pm’, most likely.

She left them to me — the novelist of the family — after she died last year, aged 89. Reading them is a poignant and fascinating puzzle, because it’s too late to ask her for any explanations.

‘Use them if you like, once I’m gone!’ my mother had told me. Well, I haven’t used them for fiction, so far; only for finding the true Frances. (We all called her Mammy until I discovered feminism in the Nineties and proposed we call her by her own name.)

What I’ve read so far has readjusted my sense of her generation, and particularly the way they parented. Not a word they’d have used; it’s too gender neutral, for starters. In Fifties’ Ireland a mum and a dad were expected to stick to their different roles.

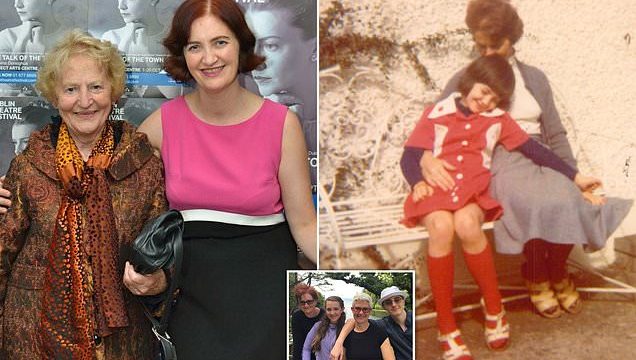

Happy childhood: Emma with her mother

When Frances and my father Denis, a professor and literary critic, married in their early 20s, she had to give up her job at Aer Lingus right away. As Irish Catholics of their day, they welcomed each of the eight ‘accidents’ that God sent. My mother’s task was to be Mammy, endlessly on call.

My own story is very different. I knew I was a lesbian at the age of 14, and left the Catholic church soon after when I realised it was unlikely ever to accept same-sex relationships. I fell in love with a Canadian woman, Chris, a professor like my dad, whom I met at a seminar at Cambridge University when I was 24 and she was 31.

And a quarter of a century later, we are raising the two children — Finn, 15, and Una, 12 — we conceived with the kind help of an anonymous sperm donor and I carried.

My mother’s Catholicism didn’t stop her from being delighted about our children’s arrivals, even if she found our methods novel.

It amuses us all that Una and Finn seem to have inherited just as many traits from Chris by nurture — tidiness in Una’s case, and a passion for fitness in Finn’s — as from me (their biological mother), by nature and nurture combined.

Unlike my parents, Chris and I have never felt the need to play distinct parenting roles; we’re both dedicated to our careers, and hands on with the children, too. It helped that she got six months’ parental leave after each time I gave birth, which we could all spend together as a family. My dad’s work offered no such opportunities.

When I’m home I’m more of the default mum, maybe, but I’m happy to leave all the laundry and cleaning to Chris, and when I’m away doing book events, I know she’s on top of everything; it’s such a relief to me that I don’t have to be their only mother.

My parents didn’t fuss and hover over their children in a way so many of us feel we have to nowadays. Each new baby was toted along for drives in a sidecar, no mention of seatbelts.

All together: From left, Emma, Una, Chris and Finn

The young mums and dads went out to the pictures and cafes a lot, leaving the baby with a neighbour or, when he was older, with the neighbour ‘listening out’ from her own house in case of loud cries.

Today, parents tend not to draw such a firm line between adults and children. Frances strongly encouraged the eight of us to go up to our rooms after dinner so she and Denis could have civilised, quiet time together.

If Chris and I tried that out on Finn and Una — who’ve called us by our first names from the start, and make fun of us constantly — they’d probably point out indignantly that it’s their house, too. But back then the notion that we had ‘rights’ as children couldn’t have been further from our minds. Is it any wonder when there were eight of us?

Reading my mother’s diaries, parenthood often seems to have been more a matter of slogging through an endless round of chores and illnesses, so many of the little miseries from which modern technology insulates us — daily shopping on foot, nappy washing, putting up shelves (him) and sewing everyone’s clothes (her), measles, mumps, chickenpox … She and my dad had each lost a little brother to childhood illness. What they’d have given for vaccines!

Nowadays parents are expected to take photos and videos of each magic moment of childhood and ‘share’ with a wide circle. But in her diaries Frances usually sounds eager to get the baby onto the next stage fast (‘breaking him in,’ which sounds like early sleep training, then weaning off the breast, getting him into his high chair or onto the potty), but not because a paediatrician was making her nervous about his reaching developmental milestones — more to get the inconveniences of infancy over with.

Frances and Denis certainly weren’t fretting over whether there were harmful chemicals in the plastic bottles, or whether they were playing with the baby enough, like I did. They didn’t worry about whether he was hearing enough Mozart (though in fact listening to classical music on BBC’s Third Programme was the nearest thing they had to Netflix.)

Supportive: Emma with her mother Frances who died last year

And there was always the next infant coming along to usurp the role, so maybe she couldn’t afford to baby any one of them as long as we might nowadays.

Girl No. 1 arrived a year and a half after Boy No. 1, and at one point my mother would be minding five under the age of eight.

I think I’m lucky to have come along at the end, the ‘runt of the litter’, as Frances joked; the household was calmer, more of a well-oiled machine by then.

Yet her approach to motherhood was ahead of its time in some ways. She signed up for a course in Active Childbirth, for instance, and gave birth to us all without drugs. She was always studying something to ‘keep her brain alive’, and she would go on to earn two more master’s degrees (in social science and film) on top of the one she had in English.

From her 40s, when I was small, she worked as a school guidance counsellor to help other teenagers find their paths, as she’d figured out how to do for us.

She encouraged her daughters to focus on their careers first — and not to have half as many children as she had. She wrote autobiographical pieces for radio which turned into a vivid memoir of her childhood in Thirties’ Dublin.

In fact, it’s her descriptions of the everyday that I find most evocative. The walks and picnics, digging the garden and reading by the fire, small domestic triumphs — ‘Very successful steak-and-kidney pie’ — and disasters such as frozen pipes and a broken sewing machine.

She revels in the arrival of modern novelties: their first plastic tablecloth, motorbike, vacuum cleaner. As I turn the pages, I can taste her pleasures: ‘gala trifle’, liver casserole, gooseberry charlotte, a ‘glamour lunch’ of hors d’oeuvres and shellfish, and ‘steamed fruit puddings — yum!’

By the time she promised me her diaries, Frances was in her 80s and knew she was in the early stages of dementia. Funnily enough, her impressive vocabulary was a help then, because when she forgot a basic word she could reach for a fancier one.

Gradually, over about seven years, she lost the plot (as she’d have put it, with her rueful humour). The diary-keeping slowed and then stopped in 2013, but she always remained fascinated by words, reading them out from street signs or menus.

Even when her nonsense phrases had no content left in them, they communicated.

‘Beautiful,’ she murmured, in her final year, when our then ten-year-old daughter played piano for her at the nursing home. Frances often said she didn’t want to live into her 90s with this illness, and, indeed, she died just before her 90th birthday.

As soon as I started to read her diaries, I felt comforted, closer to my mother. They make me shed the occasional tear, but mostly I’m grateful they’re letting me rediscover the brilliant woman when she still had all her wits about her and so much going on in a full life.

The tireless traveller (cycling along the Danube, hiking through Ecuador, crawling along the ridge of Ireland’s highest mountain to celebrate her 70th). The reader, concert-goer, mother of our clan.

And it’s through reading her words that I’ve started to realise that for all our differences, I’m the mother Frances made me: I serve up spaghetti at top speed; I always have a book on the go and a tune I’m vaguely humming; like her, I take the children around graveyards and castles, trying to bring the past alive for them.

Like Frances, I need to be me as well as a mum, and I know this will make it easier for our son and daughter to grow up and leave when it’s time. She once told me that raising children was like shooting arrows: your job was to launch them away from you.

What she didn’t say, but I noticed, was that because she did that, without clinging to or guilt-tripping us, we kept coming back home. In her later years, one of the main functions of her notebooks was to record which of her adult children and 11 grandchildren were scheduled to visit on which days, so there’d be enough beds.

I think it was a particular gratification to her to see that I got to have it all, motherhood on my own terms as well as my work life; it was a freedom that her generation of women had fought for us to have.

She was deeply fond of my partner Chris, and several times a year our noisy crew would stay in the family home in Dublin, as well as Frances occasionally coming to see us in Canada. She managed to be a real, warm presence in Finn and Una’s lives, even an ocean away.

These loose-spined volumes are the best gift she ever gave me — apart from her love, of course, and her example of a life lived to the max. Starting from the first page, I get to meet Frances young again, as she stepped out into the world for the first time.

Many of the notes she made could have come from any year in history: ‘Baby very cross, wind … dreadful night … first real teething trouble … first haha laugh … playing with rattle … the first strawberries of summer.’

Family life turns out to be the same noisy, tiring, fond business, whether today or 50 years ago, whether you’re in the kind of partnership the Pope would approve of or not.

n Emma Donoghue’s novel Room was shortlisted for the Booker and Orange prizes, and she wrote the screenplay for the Oscar-wining film adaptation. Her new novel Akin is published by Picador on October 3.

Source: Read Full Article