THE BODYWEIGHT SQUAT just wasn’t happening. Trainer Jon Flake knew it the moment Jalen McDaniels started trying to drop his 6’9″ frame into a crouch. McDaniels, a 2019 NBA draft hopeful, was beginning a workout at the Peak Performance Project facility in Santa Barbara, California. Known as P3, the gym frequently works with NBA players, and Flake, the lead performance specialist, has seen plenty of bad squats. “For many tall guys, the squat goes wrong in one of two ways,”he says.“Either they push their butt too far back or push their knees too far forward.” McDaniels was somehow fusing the two, and in this moment, he looked like he was crammed into an invisible clown car.

This wasn’t McDaniels’s fault. He hadn’t set up in a squat position that properly took into account his long limbs. Flake spotted this immediately. He handed McDaniels a trap bar, which instantly took stress off the player’s upper back and pushed him to keep his torso upright. McDaniels, who now plays for the Charlotte Hornets, started doing reps flawlessly, because he was doing a move custom-built for his body. “It’s always about finding the exercise that best suits the athlete,” says Flake.

That fit is never easy, no matter what the dude behind the counter at Planet Fitness tells you, because your body is more than just your height and weight. Different combinations of limb and torso lengths handle exercises in different ways. You may be better built to squat than McDaniels, but his long legs set him up to dominate the 20-second fanbike interval that may leave you gassed. Identify the movement advantages and disadvantages of your body type and you can unlock muscle-building potential while also avoiding frustration.

The study of these body proportions is something called anthropometry, and it’s rarely optimized for the gym. It first came to prominence in the 1880s, when Frenchman Alphonse Bertillon, who worked in the Paris police records department, began cataloging limb lengths and other details of suspects and criminal offenders for identification purposes. The goal of anthropometry is to break down body measurements beyond height and weight, chasing nuanced data on such things as the lengths of your torso, your arms, and your legs. This information is most commonly used in ergonomics, aiding in the design of objects like chairs and tables. One of the largest anthropometric studies came from the U. S. Army. It analyzed data from more than 11,000 soldiers to help better design equipment.

The closest muscle-heads came to anthropometry was in the discussion of body types, called somatotypes, which first appeared in the 1940s. Set forth by psychologist and physician William Sheldon, Ph.D., M.D., the somatotype system categorized people as ectomorphs (tall and lean), mesomorphs (athletic and strong), or endomorphs (heavy and round). His theory was that your body type dictated how easy or hard it would be to build muscle and lose weight.

Numerous experts have debunked Dr. Sheldon’s theories, yet we still think in body types. Thanks to pop culture and social media, many of us grew up with the perception that a strong body meant Arnold biceps and Chris Evans abs. If our arms were longer and skinnier than theirs, we assumed we’d never crush it in the gym. Many still believe these ideas, but they shouldn’t. Every body can be strong and pull off great feats of strength. The key is learning to train with exercises matched to your specific body type.

That’s why anthropometric training can be life changing. Fitness experts credit the late Canadian kinesiology professor David A. Winter, Ph.D., with connecting the dots between limb length, exercise performance, and forging strength. In his iconic 1979 book, Biomechanics of Human Movement, he analyzed data from research on cadaver limb lengths and started linking it to the way the body moves. His insights gained traction only with forward-thinking trainers, even though limb length can make a 225-pound barbell deadlift a breeze for one person and a nightmare for another.

Jon Flake and a handful of trainers are starting to incorporate these ideas into their work. Make a few training tweaks based on your limb measurements and you can optimize key exercises and avoid nagging injuries at the same time. There are five key combinations of arms, legs, and torso that can dramatically affect the way you lift and move. Understand them and you’ll put yourself on the path to major gains.

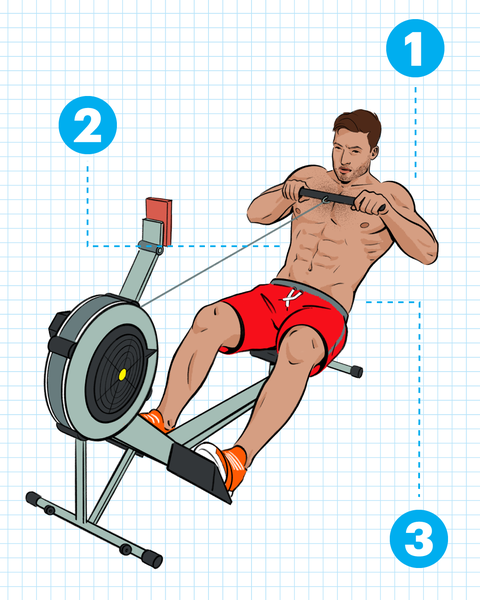

1. The Skyscrapers

Long-Limbed Men Over 5’10”

Your Challenge: Think of your body as an elevator, driving a weight upward every rep. The taller you are, the more floors the weight needs to travel on any exercise. So you need a split second longer than most people to complete each rep of each exercise. That adds up to extra work (and time spent under tension) for every muscle on every rep.

How You Adjust

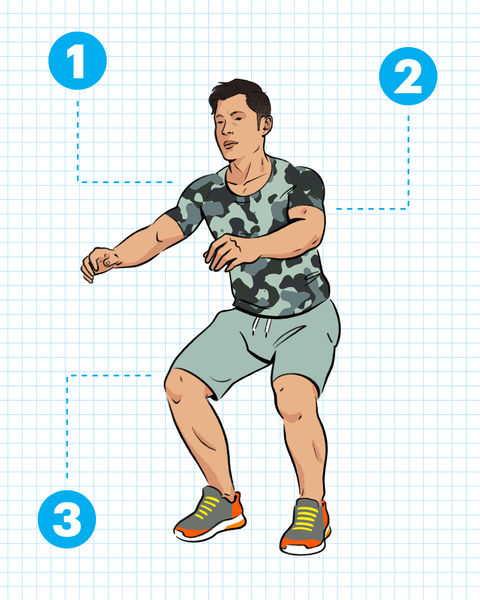

2. The Tanks

Anyone 5’7″ and Under

Your Challenge: Power production isn’t your strength. Your short limbs will hold you back when you take on the 500-meter row or test the broad jump. Short athletes generate less power per stroke than taller athletes, according to a study of competitive 2,000-meter rowers.

How You Adjust

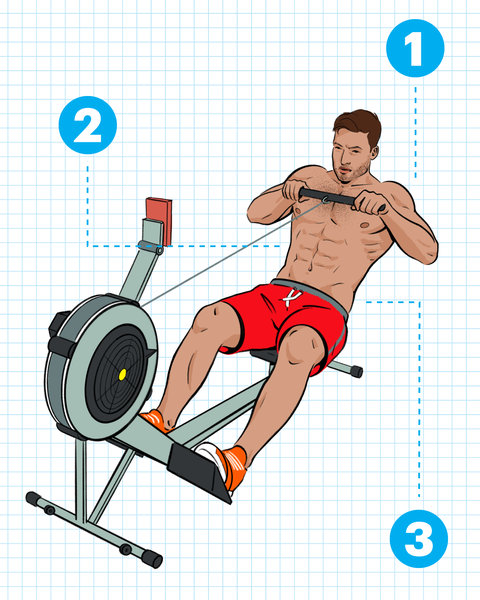

3. The Boats

Guys with Long Torsos

Your Challenge: The average person has a torso that makes up about 30 percent of their total height, measured from hip bone to shoulder. If yours is longer than that, weighted moves that have your torso bent forward, like deadlifts and rows, can be daunting.

How You Adjust

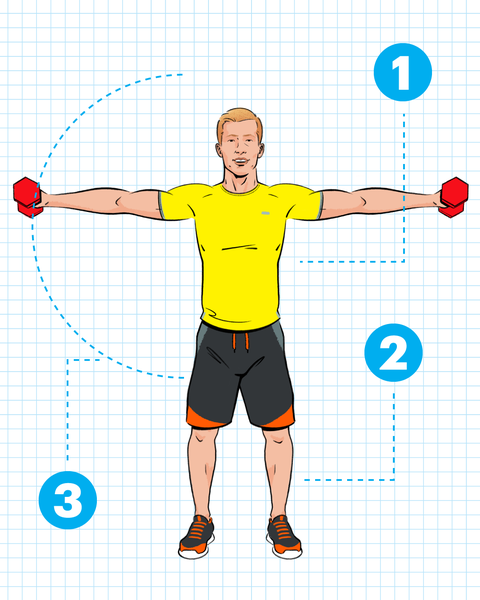

4. The Cavemen

Long Arms, Short Legs

Your challenge: Plenty of guys with shoulder issues—and this is a problem for you more than most. Overhead movements like pullups and shoulder presses, and explosive lifts like barbell and kettlebell snatches, place your shoulders at risk, thanks to the long arm lever you create as you thrust upward.

How You Adjust

5. The T-Rexes

Short Arms, Long Legs

Your challenge: You have a natural build for distance running. Strength training? Not so much. Your short arms make deadlifts difficult. And your long legs are the bane of your existence, creating a heavy load for your core on ab exercises and causing problems on lower body-focused moves, too.

How You Adjust

Size Matters Elsewhere, Too

Your arms and legs aren’t the only body parts that influence your training. The size of your hands and the length of your feet play underrated roles. So know how your appendages hurt (or help) you in the gym.

Give Yourself a Hand

Wrap your hands around a standard barbell. Can your thumb reach the second knuckle on your middle finger? If so, you have large hands that can easily wrap around any bar. If your thumb can’t reach your first knuckle, you’re more likely to lose your grip on any bar. The fix: Do plate pinches. Stand with your arms at your sides, fingers pinching a pair of 5- or 10-pound plates for 30 seconds.

Find Your Footing

Do you wear a size 12 shoe or larger? Your large feet will help you in just about any leg exercise, providing stability the same way a wider base keeps a table from rocking. If your shoe size is smaller than a 9, on the other hand, you’ll have to work harder to stay balanced on leg moves. So train the rest of your lower leg to deliver even more stability; do 3 sets of 20 calf raises at least twice a week.

A version of this story originally appears in the June 2021 issue of Men’s Health, with the title “EVERY BODY IS STRONG”.

Source: Read Full Article