Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

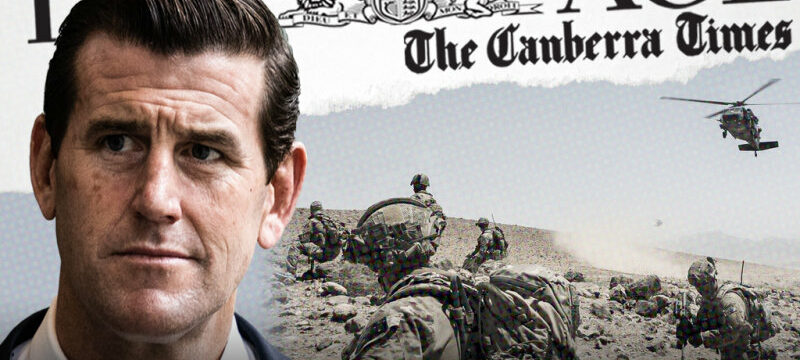

One of the nation’s biggest defamation judgments will be delivered on Thursday when the Federal Court rules on Ben Roberts-Smith’s multimillion-dollar case five years after the decorated former soldier filed the lawsuit.

Roberts-Smith – who was awarded the Victoria Cross, Australia’s highest military honour, in 2011 for his actions in a 2010 battle in Tizak, Afghanistan – alleges The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Canberra Times wrongly accused him of war crimes, bullying a fellow soldier, and an act of domestic violence against a former lover in a series of stories published in 2018.

Nine News Sydney obtained a photograph of Roberts-Smith relaxing by a pool in Bali on the eve of the judgment on Wednesday. He is under no obligation to attend the Law Courts building on Macquarie Street for the decision.

Ben Roberts Smith relaxing by a pool in Bali.

Justice Anthony Besanko will rule on whether defamatory meanings were conveyed by the articles and whether Roberts-Smith was identified by the six reports, four of which did not name him, and then consider any defences as required.

Besanko concluded public hearings in the case in July last year, after 110 days, 41 witnesses and more than $25 million in legal costs, and will deliver the judgment at 2.15pm.

Roberts-Smith, a former Special Air Service Corporal who served in Afghanistan, took leave from his role as general manager of Seven Queensland during the defamation case. Seven West Media chairman Kerry Stokes is bankrolling his lawsuit using private funds.

“[It’s] the biggest defamation case we’ve ever had, at least in recent times, because of the nature of the reporting, the seriousness of the allegations and the status of the claimant,” said University of Melbourne Law School Associate Professor Jason Bosland, director of the Media and Communications Law Research Network.

“All of those things have come together to mean this is probably the most important and significant defamation case [in Australian legal history],” he said. It amounted to “a battle between his right to vindicate his reputation and the media’s right to engage in serious investigative reporting”.

“The case is also significant because it is a quasi-war crimes investigation,” Bosland said.

There have been longer-running defamation cases, including the late Sydney lawyer John Marsden’s multimillion-dollar suit against the Seven Network, which ran from 1995 to 2003 and included a trial spanning 214 days, 113 witnesses, and three appeals on preliminary issues to the High Court.

The Marsden case was “extraordinary in its dimensions”, trial judge David Levine said in 2001, adding that “as far as I know it has been the longest and ‘biggest’ defamation action in this country’s history”.

Marsden was awarded close to $600,000 in damages in 2001, but reportedly received millions in 2003 after the parties reached a settlement following a Court of Appeal decision ordering a retrial on damages.

The newspapers argued the first four of six articles did not identify Roberts-Smith and none conveyed the meanings he alleged, but they sought to rely chiefly on a defence of truth.

As part of that truth defence, the newspapers alleged Roberts-Smith was involved in the murder of five unarmed prisoners while on deployment in Afghanistan between 2009 and 2012, contrary to the rules of engagement that bound the SAS. Roberts-Smith denies the claims.

Bosland said that if the court found in the outlets’ favour it would vindicate the media’s role in such investigations.

“It will demonstrate the public value in this form of journalism,” Bosland said. “It’s unusual for the media to win on truth alone, so if that happened it would be very significant.”

If Roberts-Smith won the case it would be a terrible loss for the media, he said.

“It’s likely to be a massive damages payout, and [it] demonstrates, I think, the difficulties that the media face when wanting to publish these sorts of stories,” Bosland said.

But Bosland said a significant consideration for all prospective defamation plaintiffs was the additional scrutiny that might flow from a trial.

“It really does demonstrate the downside of bringing defamation claims because it can expose you to further reputational harm” even if the case was ultimately won, he said.

The newspapers could not use a new public interest defence in Australian defamation law because it was introduced in most jurisdictions in 2021, well after the articles were published.

Dr Michael Douglas, senior lecturer at the University of Western Australia Law School, said: “Whatever the outcome here, I am sure that the media respondents would have wished they had the benefit of the new [public interest] defence in this case. The defence’s rationale is to protect public interest journalism.”

Under the new defence, which has yet to be tested in the context of a full trial, a publisher must prove the allegedly defamatory matter “concerns an issue of public interest” and they “reasonably believed that the publication of the matter was in the public interest”.

Douglas said that “journalists will feel more comfortable speaking truth to power if they know they have a shield for reasonably believing the publication was in the public interest”, although he warned “not all journalism will be protected, even under the new law”.

He added that “the money spent on lawyers in this litigation would be eye-watering” and “it shows that large-scale defamation litigation is still a rich man’s game”.

“Public figures may have more to lose when defamed, but everyone should have access to justice,” he said.

Follow live coverage online from 1pm, Thursday.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article