Should Britain’s greatest cultural institutions cut their links with the family dubbed ‘drug dealers in Armani suits’? The V&A, the British Museum, the Tate, Kew Gardens… they’ve all taken money from dynasty linked opioid disaster, writes TOM LEONARD

- The Sackler family and Purdue Pharma stand accused of causing an opioid crisis

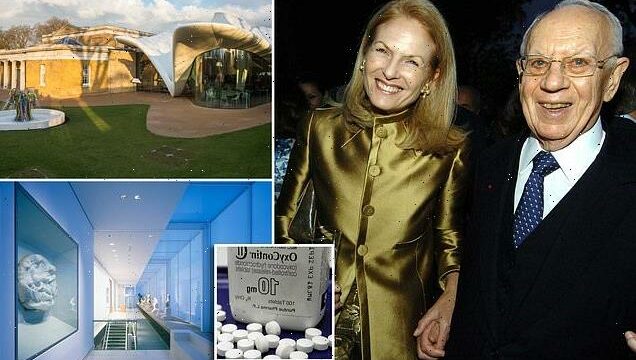

- Sackler Serpentine Gallery opening was the highlight of London’s 2013 calendar

- But today recipients of Sackler money prefer to keep the connection very quiet

- OxyContin – the opioid that made Sacklers billions – identified in 3,000 lawsuits

With its heady mix of art, beauty, politics and money gathered together under one eccentrically designed roof, the gala dinner to celebrate the opening of the Sackler Serpentine Gallery was the highlight of London’s 2013 social calendar.

Hosted by billionaire technology tycoon Michael Bloomberg and the then Vanity Fair magazine editor Graydon Carter, it drew a glittering crowd to the former gunpowder store in Kensington Gardens.

The guest list included many of the capital’s most famous and influential faces, from Top Gear star Jeremy Clarkson to then London mayor Boris Johnson and Chancellor George Osborne.

Also there were the socialites Jemima Khan and Pippa Middleton, Chelsea FC owner Roman Abramovich, the U.S. ambassador Matthew Barzun and the late entrepreneur Sir David Tang.

All were there to lavish thanks on the gallery’s donors and chief among these was Dame Theresa Sackler, representing herself and her late husband Dr Mortimer Sackler, who had died three years earlier aged 93.

For Dame Theresa, it was just one more opportunity to lap up the applause for her family’s unending largesse.

Over the years, Britain has been graced with the British Museum’s Sackler Rooms, Oxford University’s Sackler Library, Tate Britain’s Sackler Octagon, the Royal Academy’s Sackler Gallery, the Royal College of Art’s Sackler Building and the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Sackler Courtyard.

Through three family charities, the Sacklers are estimated to have given almost £170 million to grateful museums, arts organisations and universities in the UK since 2010.

But what a change in the family fortunes. Today, recipients of Sackler money prefer to keep the connection very quiet, let alone toast it. For the family and their pharmaceutical company, Purdue Pharma, stand accused of causing an opioid addiction crisis in the U.S. that has ruined or cut short millions of lives.

Dame Theresa Sackler (right) with her husband Dr Mortimer Sackler who died in 2010 at the age of 93

OxyContin — a powerful opioid-based prescription painkiller that made the Sacklers many billions of dollars — has been identified in at least 3,000 lawsuits brought by authorities, hospitals and individuals across the U.S. as the drug that set addicts on their road to ruin.

Users would often develop a craving for OxyContin and, when the pills ran out, seek substitutes including heroin and fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to 50 times as potent as heroin.

Fentanyl is now the primary cause of an overdosing catastrophe that has killed 500,000 Americans at the current rate of 274 a day.

The tsunami of outrage and lawsuits, which say Purdue deliberately misrepresented OxyContin’s risks and benefits, have been sufficient to send the company into bankruptcy and prompted the Sacklers — who’ve denied any wrongdoing — to halt their campaign of philanthropy which critics, including art photographer and anti-Sackler activist Nan Goldin, have decried as ‘reputation laundering’.

However, in recent weeks it has been revealed that the Anglo-American family — described by the mayor of one city ravaged by OxyContin as ‘drug dealers in Armani suits’ — has quietly resumed its UK donations, albeit on a less showy scale, a year after suspending them.

In 2020, good causes including the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra, King’s College London and the Watermill Theatre in Berkshire were pledged a total of more than £3.5 million grants from the Sackler Trust.

The news will inevitably infuriate those who have demanded Dame Theresa, the trust’s chairwoman, be stripped of the title bestowed on her in the 2012 Queen’s birthday honours list and for the family to stop linking its name to good causes.

The Sackler family and their pharmaceutical company, Purdue Pharma, stand accused of causing an opioid addiction crisis in the U.S. that has ruined or cut short millions of lives. Pictured: OxyContin pills

The attacks on Dame Theresa — a former convent primary school teacher in Notting Hill who was 33 years younger than her husband — and her family are likely to intensify following the release of an acclaimed TV drama series, Dopesick (shown in Britain on the streaming network Disney+) which represents a searing indictment of the Sacklers.

Its star, Michael Keaton — who won a Golden Globe for his performance last month — has revealed a compelling personal reason for wanting to make the drama: his own nephew, also called Michael, died in 2016 after overdosing on heroin and fentanyl in his early 30s at home in Pennsylvania.

Keaton, an executive producer of the series, said he told his sister Pam, Michael’s mother, that ‘the number one reason I’m doing this is for Michael and you and for everyone out there’, adding that he ‘takes pride’ in ‘holding those people accountable for the victims of this opioid crisis’.

He said: ‘There were moments where we were reading the script, and you would say: ‘Jeez, this is Michael’s story’.’

The Oscar-nominated actor plays a well-meaning doctor in an Appalachian mining town who is cajoled by one of Purdue’s army of salesmen into prescribing OxyContin for his patients.

The Sacklers come across as amoral, greedy and dangerously deluded villains in the drama.

‘We need to start thinking about how we can cure the world of its pain,’ intones future Purdue chairman and president Richard Sackler — Mortimer’s nephew — in Dopesick. He makes no secret of his mission to turn OxyContin — which was released in 1995 — into Purdue’s first ‘billion-dollar drug’.

Its critics say the company knew the drug was highly addictive yet continued to market it as addiction-free.

Purdue chiefs were aware the drug was being widely abused, as addicts crushed the pills and snorted them to bypass their 12-hour ‘time release’ design and achieve an instant high. Yet despite this, they aggressively pushed them in ever bigger doses, vastly increasing the risk of addiction and fatal overdose.

Keaton says that Purdue behaved so cynically, it ‘makes the tobacco industry look like shoe salesmen’.

The opioid crisis is estimated to be costing the U.S. nearly $80 billion a year, not to mention the lasting agony it inflicts on families. Crime has soared across America partly as a result. In some areas, OxyContin-related crime has been blamed for as much as 80 per cent of offences.

The opening of the Sackler Serpentine Gallery (pictured), with its heady mix of art, beauty, politics and money gathered together under one eccentrically designed roof, was the highlight of London’s 2013 social calendar

Some doctors drastically over-prescribed it, the most unscrupulous and greedy ones setting up ‘pill mills’ that churned out prescriptions.

OxyContin became popular with drug-abusing celebrities, including singers Michael Jackson and Prince, and actors Heath Ledger and Philip Seymour Hoffman. All of them died from overdoses that involved prescription drugs.

Billionaire banking heir Matthew Mellon, the ex-husband of British shoe designer Tamara Mellon, died in a Mexico rehab facility after battling OxyContin addiction. He had denounced it as ‘legal heroin’.

Compared to the epidemic in the U.S., recreational use of OxyContin in the UK remains relatively rare. However, nearly 2,300 people died from drug poisoning involving opioids in the last year, a 48 per cent rise since 2010, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Late last year, in the first jury verdict in an opioid case, a court found that three of America’s biggest pharmacy chains — CVS Health, Walmart and Walgreens — had not stopped the flood of pills in two Ohio counties that caused hundreds of deaths and cost each county about $1billion. If similar results are replicated across the U.S., the eventual bill could be astronomical.

In 2020, after years of quietly settling lawsuits out of court, the company admitted criminal charges connected to its marketing of OxyContin. The company and senior executives admitted exploiting doctors’ misconceptions about the drug’s strength, telling medics and patients that it was less addictive than it really was.

Over the years, Britain has been graced with the British Museum’s Sackler Rooms, Oxford University’s Sackler Library, Tate Britain’s Sackler Octagon, the Royal Academy’s Sackler Gallery (pictured), the Royal College of Art’s Sackler Building and the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Sackler Courtyard

The Sacklers themselves agreed a $4.5billion (£3.3billion) settlement with U.S. states in return for immunity from prosecution in any future civil actions. However, following appeals from several U.S. states and a U.S. bankruptcy watchdog who noted the Sacklers had extracted more than twice that sum in just nine years, a judge overturned the settlement. Purdue says it will appeal.

The Sacklers, estimated still to be worth $11billion, refuse to accept personal responsibility, insisting they ‘acted lawfully and ethically’ and none of them has faced criminal charges.

The renewed attention to the scandal has raised questions of whether it is time to purge the tainted Sackler name from the museums and galleries in Britain and America.

The beneficiaries of their money are easy to spot. The Sacklers have long been notorious in the charity world for their insistence that their name be prominently plastered on everything they support.

Even a modest footbridge over the lake at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is grandly named the ‘Sackler Crossing’, while an escalator at Tate Modern is laughably called the ‘Sackler Escalator’.

The Louvre in Paris and New York’s Metropolitan Museum have removed the Sackler name, as has London’s Serpentine Gallery where that star-studded evening was held just nine years ago. But the British Museum, Tate, V&A and National Gallery have yet to follow suit.

OxyContin — a powerful opioid-based prescription painkiller that made the Sacklers many billions of dollars — has been identified in at least 3,000 lawsuits brought by authorities, hospitals and individuals across the U.S. as the drug that set addicts on their road to ruin

It doesn’t help that the family has been such generous donors. Opening the £2million Sackler Courtyard at the V&A, the Duchess of Cambridge stepped on to the world’s first outdoor space made of porcelain and was caught on camera, mouthing ‘Wow!’

The dynasty descended from a Polish-Jewish grocer from Brooklyn has certainly come a long way. Dr Mortimer Sackler, the man who was the driving force behind the foundation of the family fortune, bought Purdue Pharma in 1952 with his brothers and fellow psychiatrists, Arthur and Raymond.

They were also tough businessmen who used ethically questionable tactics to sell drugs through frequently dishonest advertising.

They became rich and Mortimer, an Anglophile who had gone to medical school in Glasgow, became a high-spending playboy, shuttling between lavish homes in England, Switzerland and France.

He settled in the UK after the Sacklers bought their first British drug company in 1966, effectively establishing a branch of the family business on both sides of the Atlantic. Mortimer later received an honorary knighthood.

Nine years after Arthur died in 1987, the brothers struck gold when they started selling OxyContin, developed after a London hospice had asked one of their British companies to come up with a form of morphine that could be taken as a pill.

The Sacklers claimed their slow-release wonder drug — which is pure oxycodone, a chemical cousin of heroin — relieved pain for 12 hours, more than twice as long as existing drugs on the market.

And for millions of people suffering chronic pain, it worked. OxyContin rapidly became America’s best-selling painkiller and by 2001, annual OxyContin sales had passed $1billion as it was being prescribed to nearly six million people. At its peak in 2010, the drug was making its owners a staggering profit of $3billion a year.

Users would often develop a craving for OxyContin and, when the pills ran out, seek substitutes including heroin and fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to 50 times as potent as heroin

Corporate success came at a terrible cost. The Sacklers maintained that they and Purdue were blameless for any abuse of the drug, as OxyContin was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, concerningly, the FDA official who had endorsed Purdue’s claim that OxyContin was virtually addiction-free, was handed a high-paying job with the company after he had approved the drug.

Purdue sales reps were told to play down its risks as the company ferociously targeted not only cancer specialists and hospices but GPs, dentists and nurses, arguing that OxyContin could be prescribed for back pain, sports injuries and even toothache. At the same time, it brought out ever stronger doses of the drug.

While many doctors genuinely believed in the drug, thousands of practitioners were paid to publicly talk up OxyContin’s merits. GPs were offered financial benefits for prescribing it and further enticed with all-expenses-paid trips.

The Purdue salesmen, who competed to win holidays to Bermuda by selling the most pills, regurgitated the company’s claims that OxyContin’s risk of addiction was ‘less than one per cent’ and that it was a cure-all for almost any pain.

Fentanyl is now the primary cause of an overdosing catastrophe that has killed 500,000 Americans at the current rate of 274 a day (file picture of assorted pills and prescription drugs)

But it was in fact highly addictive — as became tragically clear when the drug started being prescribed for even moderate pain.

‘We were directed to lie. Why mince words about it?’ Shelby Sherman, a former Purdue sales rep, told Esquire magazine. ‘Greed took hold and overruled everything. They saw that potential for billions of dollars and just went after it.’

In 2003, the U.S. government’s Drug Enforcement Administration found that Purdue’s ‘aggressive methods’ had ‘very much exacerbated OxyContin’s widespread abuse’, and lawsuits against the company started to pile up.

At the Serpentine Gallery’s event in 2013, London Mayor Boris Johnson gave a speech in which he said that while rich British people celebrated their success by ‘buying the biggest house they can, with the most colossal grouse moor’, in America ‘they believe that if you have made a lot of money you should do something for society’.

Nobody could deny the Sacklers and OxyContin have ‘done something’ for society. But it’s hardly something we should celebrate.

Source: Read Full Article