Romans invented recycling: Pompeii excavations reveal rubbish was collected, sorted and resold

- American academic Allison Emmerson has helped unearth findings at Pompeii

- Roman city was completely destroyed by eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD

- Rubbish mounds outside city walls were in fact sorted piles to ‘use’ and ‘reuse’

- Broken ceramic sherds, tiles and plaster could be used as construction material

- New research features in Emmerson’s book, Life and Death in the Roman Suburb

As master engineers, the Romans were way ahead of us on everything from underfloor heating to aqueducts that could transport water for miles, among other wonders of the ancient world.

Now it emerges they were just as advanced when it came to disposing of their rubbish – and were the ultimate recycling society, according to the latest research.

Professor Allison Emmerson, an American academic, is part of a large team that has been working extensively at Pompeii, the Roman city destroyed by the violent eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

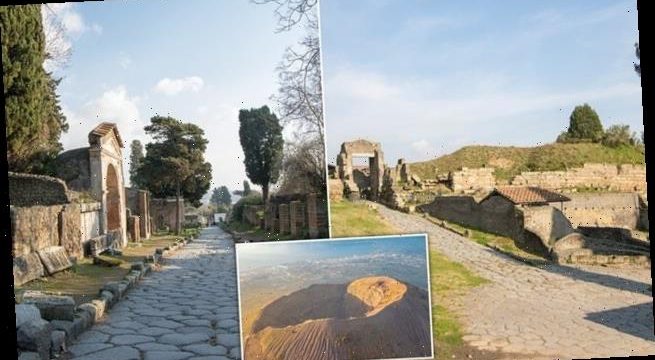

A team of experts has revealed that mounds of ancient rubbish found in Pompeii, including here in the Porta Ercolano suburb, were in fact piles deliberately made for recycling material

A photograph from 1942 shows the ancient rubbish piled high against the city walls of Pompeii

They have concluded that huge mounds of garbage that had seemingly just been dumped outside the city walls were in fact ‘staging grounds for cycles of use and reuse’, filled with material that could be incorporated into buildings, such as filling earth floors.

She said: ‘We found that at least part of the city was built out of trash. These piles aren’t outside the walls, because it’s material that’s been dumped outside to get rid of it. They’re outside the walls very purposely, being collected and sorted to be resold inside the walls.’

Almost the entire external wall on the city’s northern side, among other sites, had garbage piled up, with some of the mounds several metres high.

Although most of the mounds were cleared in the mid-20th century, long before garbage became a topic of scholarly interest, they are still being discovered today.

When the Porta Nocera subrub was excavated by archaeologists in the mid-20th Century, rubbish covered the roads and was piled high, in and around the buildings

Professor Emmerson said these mounds were previously thought to have been rubble from a dramatic earthquake that struck around 17 years before the volcanic eruption, but that the contents of the mounds do not resemble debris from a natural disaster.

They include typical urban waste, along with ceramic sherds, tiles and plaster that – when collected up into vast quantities – became a valuable construction material.

She added: ‘The idea has been that all this garbage is the result of that earthquake – rubble that was cleared out of the city and dumped outside of it.

‘As I was working at Pompeii, outside the urban area, I thought this was very strange because I see the city really extending outside the walls into the suburbs…. So it didn’t make sense to me that they were also being used as landfill.’

With fellow archaeologists Steven Ellis and Kevin Dicus of the University of Cincinnati’s Pompeii excavations, Emmerson has studied how the ancient city was constructed, using scientific analysis to detect differences in dirt and soil and track the movement of garbage and its ultimate reuse.

Emmerson said that, while there has been debate about garbage in the Roman world, the latest research gives unprecedented detail of how it was collected and recycling: ‘What I’ve done is trace its path.

The ruins of Pompeii, as it looks today, with Mount Vesuvius in the near distance behind

‘You gather up your garbage…it gets moved out into either abandoned lots inside the city or in largest quantities out into open spaces outside the city where it can really gather in very large quantities, which make it valuable, just like modern recyclables. It becomes valuable en masse.’

She said: ‘The difference in soil allows us to see whether the garbage had been generated in the place where it was found, or gathered from elsewhere to be reused and recycled.’

Emmerson noted that some walls at Pompeii, for example, include materials ranging from tile pieces and amphorae to chunks of mortar and plaster, just like the material found in the ‘recycling plants’: ‘Almost all such walls received a final layer of plaster, hiding the mess of materials within.’

Professor Emmerson, who teaches Classical Studies at Tulane University, New Orleans, will include the latest research in her forthcoming book, Life and Death in the Roman Suburb, published next month by Oxford University Press.

She said that today’s processing of waste is based on removing it from our daily lives: ‘For the most part, we don’t care what happens to our trash, as long as it’s taken away from us.

Mount Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii in an eruption in AD 79 and is still an active volcano today

‘What I’ve found in Pompeii is an entirely different priority, that waste be collected and sorted for recycling.

The Pompeians lived much closer to their garbage than most of us would find acceptable, not because the city lacked infrastructure and they didn’t bother to manage trash, but because their systems of urban management were organised around different principles.

‘This point has relevance for the modern garbage crisis. The countries that most effectively manage their waste have applied a version of the ancient model, prioritising commodification, rather than simple removal.’

HOW MOUNT VESUVIUS DESTROYED POMPEII

Mount Vesuvius erupted in the year 79AD, burying the Roman cities of Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae under up to 23ft of ash and rock fragments, and the city of Herculaneum under a mudflow.

A 500C pyroclastic hot surge and an avalanche of ash, rock and poisonous gas that rushed down the side of the volcano at 124mph (199kph) ensured there were no survivors.

Pyroclastic flows are ultra-fast streams of hot gas and volcanic matter that spew forth from some eruptions.

The residents of Pompeii were buried in up to 23ft of ash when Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD79

They are more dangerous than lava because they travel faster, at speeds of around 450mph (700kph).

The thermal heat generated by the explosion is thought to be around 100,000 times that of the two atom bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

An administrator and poet called Pliny the younger watched the disaster unfold from a distance.

Letters describing what he saw were found in the 16th century.

His writing suggests that the eruption caught the residents of Pompeii unaware.

He said that a column of smoke ‘like an umbrella pine’ rose from the volcano and made the towns around it as black as night.

People ran for their lives with torches, screaming and weeping, he wrote.

The rapid burial of Pompeii meant that it remained extremely well preserved.

Mount Vesuvius, on the west coast of Italy, is the only active volcano in continental Europe and is thought to be one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. It has erupted four times in the past 200 years.

Pompeii’s secrets continue to be uncovered to this day.

Source: Read Full Article