Hounding of a hero: As a British officer decorated for valour is now being investigated for the EIGHTH time over the death of an Iraqi 16 years ago, RICHARD PENDLEBURY asks is it any wonder Army recruitment is in crisis?

- Robert Campbell is in his 17th year under suspicion of the ‘murder’ of teenager

- Said Shabram, 19, drowned in a river in the city of Basra in May 2003

- On seven occasions Mr Campbell has been cleared and told ‘case closed’

Robert Campbell meets me at the railway station in the provincial town where he lives. He said he’d be easy to recognise — and he was right. Just 46 years old, he has hearing aids and walks stiffly with the help of a stick.

He struggles with mental health issues, suffers failing eyesight and needs both hips replaced. And he not only feels abandoned by the very organisation he used to call ‘home’ — but hunted down.

This highly decorated former major in the Royal Engineers finds himself in a situation that, even by the lamentable standards of our military’s duty of care, is surely unique.

Mr Campbell is now in his 17th year under suspicion for the ‘murder’ of an Iraqi teenager who drowned in a river in the city of Basra in May 2003. Eight official investigations have taken place into his alleged role in the death of 19-year-old Said Shabram, for which Mr Campbell and two other former soldiers in the Royal Engineers deny any culpability.

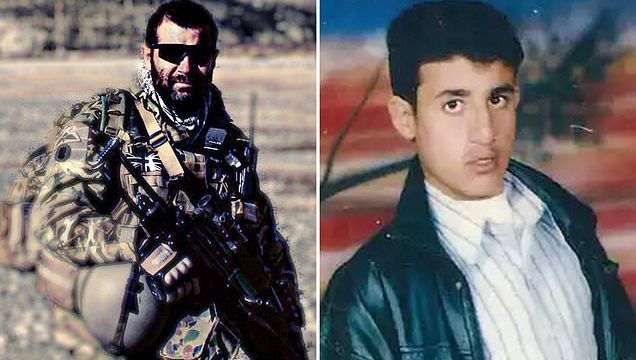

Robert Campbell (pictured) is now in his 17th year under suspicion for the ‘murder’ of an Iraqi teenager who drowned in a river in the city of Basra in May 2003

On seven occasions, he has been cleared of all blame and told ‘case closed’ — only for inquiries to be reopened soon afterwards. During this time, he was deployed to fight on four tours of Afghanistan.

The eighth investigation — by a Ministry of Defence quango called the Iraq Fatality Investigations (IFI) — is likely to drag on for years after the retired High Court judge leading it died in June. He will be replaced, and the Campbell case will have to start all over again.

‘I’m in a horrendous kind of limbo,’ says Mr Campbell. ‘I’m not aware of another case that has been quite so hashed over.’

Ranged against him have been the Royal Military Police, investigators from the now-defunct Iraq Historic Allegations Team, Iraqis determined to win compensation, a corrupt human rights lawyer, and a Ministry of Defence that, he claims, sought to protect politicians and military officers responsible for the disaster in Iraq by throwing innocent soldiers to the wolves.

Mr Campbell speaks with a fluency born of passion at the injustice he has suffered and the incredulity of what he has endured. His story is both gripping and shameful.

Robert Campbell was a lieutenant in 32 Engineer Regiment when the ground phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom began in March 2003.

He was attached to the Black Watch Battle Group and found himself in Basra, a city gripped by a murderous anarchy for which the British occupation force was singularly unprepared.

The ‘unlawful killing’ incident took place against this backdrop on May 24.

Mr Campbell says he and three of his soldiers — a corporal, a lance corporal and a sapper — were washing two armoured vehicles on the bank of the Shatt al-Arab river, 500 yards from the unit’s base.

Timeline of the travesty

May 24, 2003: Death of Said Shabram in Basra. Robert Campbell and his colleagues give voluntary statement to unit commander.

First investigation, February 2004: Campbell and his colleagues are interviewed by Royal Military Police (RMP) in Germany. Case passed to Army Prosecuting Authority.

Second investigation, April 2006: Formal Preliminary Investigation conducted at Basra airport. Cleared.

Third investigation, January 2008: Allegations against Campbell and colleagues repeated in MoD’s Aitken Report. He is told by a senior officer it is just a ‘PR exercise’.

Fourth investigation: Second inquiry by RMP. Case is dropped.

Fifth investigation, December 2014: Iraq Historic Allegations Team begins inquiry into Said Shabram’s death. The case is passed to MoD’s Director Service Prosecutions.

Sixth investigation, September 2016: Director Service Prosecutions decides there is no case to answer.

Seventh investigation, October 2016: Director Service Prosecutions’ decision is reviewed by yet another new prosecutor. In January 2018, it is decided there is no case to answer.

Eighth investigation, March 2018: Case reopened by Iraq Fatality Investigations. Ongoing.

Given the uncertainty of his ongoing legal position, Mr Campbell feels he must be circumspect about describing what happened. ‘All I am prepared to say is that me and one of my soldiers almost drowned trying to fish him [the dead youth] out.

‘No one pushed anyone into the river . . . We were witnesses to rough justice being meted out by locals and those two guys jumped in the river to escape.’

The other boy — the dead man’s cousin — survived.

‘We went back to our camp and briefly told the adjutant what had happened,’ says Mr Campbell. ‘Because one of my sappers and I had gone into the river, we were sent to Battle Group HQ to be seen by the doctor. The water was foul with oil and sewage. By the time we got back to camp, a crowd of locals had gathered at the gates and it was pretty hostile.

‘We volunteered to our people what had happened. If we had done anything wrong, we could quite easily have driven away and denied any knowledge. But we reported to our chain of command.’

The written report they made that day is the statement they stand by almost 17 years later.

During the following weeks, allegations were made by locals against the engineers.

‘The Royal Military Police began to interview other people in our squadron — who had not been present — but did not interview us,’ says Mr Campbell. ‘They said they would do it when we got back to our base in Germany. At that stage, it just seemed to be a formality.’

The allegation was that Lieutenant Campbell and his men had killed the teenager by ‘wetting’ — a term allegedly used to describe the practice of putting Iraqis who were looting or engaged in some other disorder into the river. The two youths had been forced at gunpoint off a jetty, it was claimed. Mr Campbell denies this vehemently. ‘Phil Shiner — the human rights lawyer who was later struck off for dishonesty — first came up with the phrase of “wetting” as far as I was concerned, and he tried to make it out to be a common British Army punishment,’ he says. ‘I had never heard the phrase until I heard him say it years later.’

The engineers deployed back to their base in Germany that July. Nothing more was said.

Then, in early 2004, Mr Campbell was on a course in the UK when he was told he had to return to Germany immediately to be interviewed by the Special Investigation Branch. A number of alleged ‘atrocities’ by British troops in Iraq were emerging.

‘It had become very political,’ he says. ‘The zeitgeist was to investigate everything, however flimsy.’

He says the military police were ‘very professional. No malice. We were interviewed twice. They said: “There is a chance you might be reported for murder or manslaughter.” But we did not take it seriously. It was absurd’.

At first, all four soldiers were treated as suspects. Then the most junior was told he would be a witness. ‘They hoped he would “spill the beans” about the rest of us. But he had no beans to spill,’ he says. By this time, there were signs they were being officially ostracised. They had their Iraq campaign medals withheld and were not included in that year’s regimental photograph.

Months passed. The three ‘suspects’ were told they would be facing court martial. But first, the evidence would be examined by a second inquiry team.

In April 2006, Captain Campbell — he’d been promoted the previous year — and his men returned to Iraq with their legal team for what is called a Formal Preliminary Investigation, conducted in a hangar at Basra airport.

Said Shabram, 19, right, drowned in the Shatt al-Arab waterway, near Basra. Three servicemen are accused of forcing the teenager into the water as punishment for looting

In two days, the Crown’s case ‘folded’. The witnesses did not bear scrutiny. The following day, the men’s campaign medals, supposedly lost due to an administrative error, were found and handed to the cleared soldiers ‘in Jiffy bags’.

But at least the cloud was dispersed. ‘I was told: “It’s over. Get on with your lives.”

‘We were welcomed back into the “good lads club”. I was asked what posting I wanted, which I took as acknowledgement they had f***** up. And I so said EOD [bomb disposal].’

Mr Campbell did his first tour of Afghanistan in 2006-07, commanding a bomb disposal squadron. Despite bitter fighting and the constant threat of IEDs, he did not lose any men and, when he returned, was awarded a Joint Commanders Commendation.

Other plaudits followed. In June 2008, he defused a 1,000 kg Luftwaffe bomb on an Olympic construction site in London. It took 20 hours. He received a letter of thanks from then-London mayor Boris Johnson and was awarded a Commander-in-Chief Commendation. ‘I appeared to be back on track,’ he says.

But then, driving home, he heard on the radio that the Army had published The Aitken Report: An Investigation into Cases of Deliberate Abuse and Unlawful Killing in Iraq in 2003 and 2004.

Mr Campbell had not known that an investigation had been under way. He was then called by the unit adjutant who said that Campbell’s Basra case was one of those included. He was told: ‘Don’t worry, it’s just a PR exercise. No one will read it.’

How wrong he was.

‘What the dimwits at the MoD didn’t grasp was that Phil Shiner and other lawyers like him grabbed this report and said: “Brilliant!” They took it as an admission of guilt and used it as source material to round up all the witnesses for future legal actions,’ he says.

It was the catalyst for a tidal wave of spurious accusations.

Yet, when he returned to Afghanistan in July 2010, Mr Campbell believed the Basra allegations were at last behind him.

‘But then I got an email from one of my co-accused who said he had received a letter from the Treasury Solicitor’s Department — the Government’s legal team.

‘Another human rights law firm active in Iraqi cases had filed a suit claiming unlawful death on behalf of [Said Shabram’s] family against the MoD. They wanted us to make more statements.’

Mr Campbell took legal advice and was told to make no further statement, a position that he has maintained to this day.

The Government settled out of court with the family. ‘I believe they paid £100,000 to the family of the dead man and £45,000 to the guy who did not drown,’ says Mr Campbell. In making the payments, the MoD denied any liability for the death.

He later discovered that, while in Afghanistan, the Royal Military Police started another criminal investigation into him over the incident. ‘It was dropped, but can you believe the duplicity of it?’ he asks now.

Later during that tour — for which he received a NATO Meritorious Service Medal — he suffered the injuries that plague him to this day. Caught on the roof of a two-storey building in a firefight in which two of his men were killed, he jumped for his life. Wearing 60 kg of kit, the impact on landing smashed vertebrae and damaged his hips. He was flown home.

‘Now I knew I was struggling,’ he says. ‘My back was wrecked, my hearing was going and I started to have mental health problems.’

In January 2012, he ‘pretty much had a physical and mental breakdown. I was diagnosed with PTSD. They told me “go home” and then just forgot about me’.

There was no contact with the Army for four months, during which ‘I wasn’t coping’, he says.

Eventually, he recovered enough to be sent on attachment to the RAF, where he was deployed twice more to Afghanistan and, in 2014, promoted to the rank of Major.

Then came the next legal blow. ‘At end of 2014, I was on my way on holiday to Iceland when my mobile rang. It was my ex-girlfriend, who said: “There are two police here asking about the incident in Iraq . . .” They were trying that old copper’s trick of going to an ex-partner, hoping for animosity. But we got on — and she told me everything.

‘And they were not actually policemen. They were civilian investigators from IHAT [The Iraq Historic Allegations Team].’

The team had been set up by the Labour government ‘to review and investigate allegations of abuse of Iraqi civilians by UK armed forces personnel in Iraq’. It received more than 3,000 allegations of unlawful death in total. One concerned Mr Campbell’s case.

‘They asked my ex if I was a racist, alcoholic or violent. They kept trying to make her say bad things. She didn’t even know me in 2003. When I came back from holiday, I found that IHAT had contacted everyone in the Army who had contact with me.’

Mr Campbell was, at this stage, studying at staff college. His mental health relapsed.

‘IHAT investigators monitored my emails and asked my bank for my financial details. The Army handed over my service and medical records without telling me, let alone asking permission, then denied they had done so before finally admitting it.

‘What were they going to find that was of any evidential use? But they had no checks and balances. They were out of control. And the contractors (most of the IHAT staff were civilian by then) were being paid by the hour and raking it in.

‘The sapper who had been present on the day of the incident had left the Army and moved to Australia. IHAT visited him there twice. Great for them!’

Eventually, the three accused were interviewed under caution at civilian police stations.

‘They asked me a lot of stupid questions,’ recalls Mr Campbell. ‘I could see their notes and they kept writing: “Clarify with PIL” — Public Interest Lawyers, the name of Phil Shiner’s firm. They were getting directions from him.’

PIL had the best contacts on the ground in Iraq.

Mr Campbell says he had another mental breakdown and his physical injuries were deteriorating. He took sick leave in February 2016 and never went back. He returned his campaign medals to the Queen.

IHAT handed over his case to the Director Service Prosecutions (an organisation within the MoD), the sixth investigator. In September 2016, the director decreed there was no case to answer. ‘I was told once again to “forget it. It [was] finished.” ’

But, of course, it wasn’t.

A month later, while at the military rehabilitation centre at Headley Court in Surrey, where he was diagnosed with a brain injury, Mr Campbell learned the decision to drop the case had been challenged. The dead Iraqi’s family wanted it to be reviewed.

So for the seventh time, the case was investigated by a new prosecutor. In January 2018, he, too, concluded there was no case to answer.

By then, the tide had turned against the Iraqi atrocity compensation industry. Phil Shiner was facing serious professional disciplinary proceedings. His firm, PIL, closed in August 2016 and he was struck off as a solicitor after being found guilty of multiple professional misconduct charges, including dishonesty and lack of integrity.

IHAT was closed down, having spent £34 million of taxpayers’ money and been thoroughly discredited. It failed to secure a single prosecution.

But, by then, Mr Campbell learned his case was being scrutinised — for the eighth time — by the Iraq Fatality Investigations, set up in 2014 to carry out inquiries into civilian deaths linked to Britain’s military in Iraq.

The IFI was led by retired High Court judge Sir George Newman, who was paid £900 a day. But Sir George died in June.

‘The MoD have not yet advertised for his successor,’ says Mr Campbell. ‘I’m told they are working on the theory that Boris Johnson might want to make changes.’

He says the Government has promised them that any evidence they give will not be used to prosecute them, either in the UK or at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

‘But the assurances they give us are complete bull****,’ he says. ‘The MoD says that if they don’t investigate, the ICC will. But I have been told by the chief prosecutor at the ICC that their remit is to prosecute commanders and political leaders, not individual soldiers like me.’

Which, of course, brings us to what lurks behind this extraordinary case: the question of overall responsibility for the disastrous war in Iraq.

‘The people the ICC would be interested in are Tony Blair, [former Defence Secretary] Geoff Hoon, and the generals — not a lieutenant in 32 Engineer Regiment,’ says Mr Campbell.

‘I am convinced that IHAT was set up to divert the blame away from senior figures.’

Mr Campbell was medically discharged from the Army in May 2018 and feels abandoned. ‘They said: “This investigation could take years. Off you go.” ’

But where?

He cannot work because of his health and he has a wife and eight-month-old son to support.

So far, the Army has decreed he is only 14 per cent disabled and so he gets an ill-health pension ‘less than one-third of my Army pay’.

Speaking yesterday, an MoD spokesman said: ‘We recognise the significant impact that investigations into historical allegations can have on members of the Armed Forces and veterans.

‘That’s why we are consulting on a package of new measures, including a presumption against prosecution, to ensure that service personnel and veterans are not subject to legal proceedings many years after alleged events and where there is no new evidence.’

Meanwhile, Robert Campbell’s fight to clear his name goes on. It is the hardest battle he has fought.

Source: Read Full Article