Australia faces the prospect of a space race with China – not to the moon, but to the benefits of solar power generated in orbit.

A US-Australia joint venture called Solar Space Technologies (SST) has drawn up an extensive plan to build an orbiting solar-power-generated satellite network that could be operational in eight years.

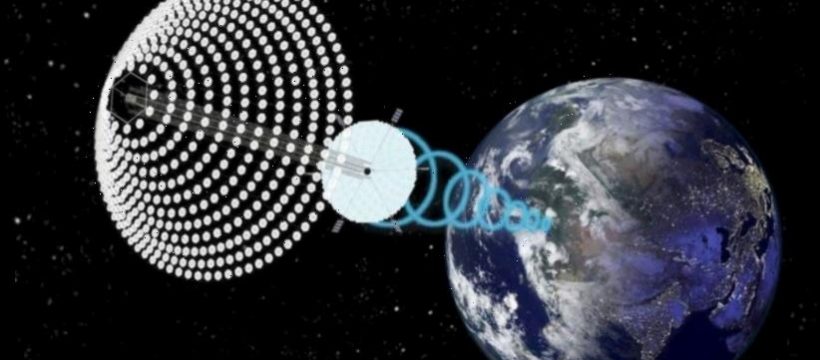

Is the time right for space-based solar power? The platform proposed by Solar Space Technologies.Credit:SST

Meanwhile, China reportedly has a well-funded team already reportedly working on a similar project.

Unlike the moon race of the past, the goal of this space race isn’t to reach a part of the solar system as much as it is to solve future energy needs through new technology.

Serdar Baycan and John C Mankins, ex-Nasa official who is an expert in space-based solar power. Credit:Joe Armao

"The nation that develops space solar power first will have the upper hand," said John Mankins, director of SST. "If one country dominates the development and establishes the standards … they will have a very strong first-mover advantage in the industry."

As a physicist at NASA and the California Institute of Techonology, Mankins knows more about space solar power than anyone. He literally wrote the book on the technology: The Case for Space Solar Power.

Such a spacecraft could capture solar energy, convert it to radio waves and beam it back to receivers on Earth called rectennas – creating a continuous source of power.

Its efficiency outstrips land-based photovoltaic solar panels – and, being parked in geo-synchronous orbit (GEO) 35,800 km above Australia, the power would be limitless and unwavering.

What’s more, there are a fixed number of slots available in GEO, making the desire to get the platform there an urgent one, lest China send theirs into orbit first. The possibility of space solar power comes as NASA seeks closer ties with Australia’s burgeoning space sector and the nation's newly opened space agency.

Whether SST or the China venture succeeds, big factors on earth are making such projects possible and more probable: climate change and advances in launch technology – but also an increased appetite for risk driven by political rivalry.

China’s challenge to the West, US President Donald Trump’s aggressive response to Beijing’s trade practices, and a reassessment of globalisation have combined to encourage a more strategic approach to trade, economies, science and technology. National concerns are starting to drive economic decisions.

So it is with space-based solar power, said SST founder Serdar Baycan and respected Melbourne architect – co-owner of the business with Mankins. SST has held talks with business and government figures on both sides of the Pacific.

"We have requested of our government to make it a national priority to leapfrog other nations to become the first nation, in partnership with the US, to implement this tech and set the standard," he said.

The goal is "to set the standard in a way to where we are able to influence the peaceful use of this technology."

The response to the company from government and private sector groups has been "extremely positive", said Mankins during a visit to Melbourne in August.

The crew of Apollo 8 captured this view of Earth in December 1968, which helped galvanise public awareness of the planet’s fragile ecology. Credit:NASA

In those days, the US had a nationalised, government-directed space program – like China does currently, Maher said.

Today, in the West, a lot of space technology "is very much based on a market model," Maher said, adding that SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin are spearheading much ground-breaking activity.

"They’re taking space out of the public sphere."

"How do we create the national will to jump back into a space race with China when our space efforts are led by three billionaires and their companies?"

To a degree, the lack of coordination simply reflects the norms of the West’s tech industry after three decades of globalisation.

In this way, China has a political advantage, because it can carry through multiyear planning without the approval of the public, said ASPI’s Davis.

"China’s government doesn’t answer to its people," he said. "It makes it decisions and carries them out and people have no say in what happens."

Yet crises tend to force the hand of a democracy. Not so long ago, the notion that Australia would need to pass laws to protect its political system from its largest single trade partner would seem absurd.

Reconsiderations about China and technology in the West, has invited a soul-searching about the relationship of technology to democracy.

Tech billionaire Peter Thiel recently castigated Google for working with the China on artificial intelligence while spurning work for the Pentagon. There was more discussion about the national interest around atomic energy when it was first discovered in the 1940s than the implications of artificial intelligence today, Thiel said in a speech.

Mankins agreed that the discussion on national interest and technology had been lacking in recent years.

"It’s absolutely true that when you have a fundamental advance in technology in a new field, it’s extremely important that thought be given to how it will be applied," he said.

If energy from space one day becomes ubiquitous, Mankins said, it’s very important for SST to be at the forefront of how it will be done, and to be aware of who benefits and who controls it.

That gets to the heart of space-based solar power, as envisioned by Mankins and Baycan.

For the orbiting energy plants to matter, it must help solve global energy needs, Baycan said.

Whether or not SST succeeds is far from clear. But if the plan attracts funding needed to get off the ground, broad public support would be a crucial ingredient.

"A fundamental issue for us," said Baycan "is that it has to be in the service of the people of Australia."

Source: Read Full Article