Football Australia has banned for life a supporter of the Sydney United 58 club who was filmed making a Nazi salute during last weekend’s Australia Cup final. Here was old mate, arm erect, amid a mob who, just in case anyone held any doubts about their intentions, also booed the welcome to country and Australia’s national anthem before launching into songs associated with the 20th century Croatian fascist group the Ustase, the Third Reich’s staunch friend in the Balkans.

Why anyone would choose a football game in Parramatta in 2022 as their moment to salute Hitler is for them to explain, but they can’t claim ignorance. They weren’t signalling for more beers or putting their hands up for a vacant AFL club CEO’s position. They can’t hide behind the protection of free speech. No loopholes, no contorted arguments over democracy, no Sky News high school debating clubs arguing for the affirmative. Just a life ban.

Oh, for the simple things.

You could say they performed a social service. It’s almost refreshing to be reminded that free speech is not a limitless right purchased unconditionally with the entry ticket to a football match. And that anyone who bans a fascist is not a fascist too. No. Some gestures, whatever the vacancy of the brains rattling around behind them, are beyond tolerating.

The reminder is also useful during a week when the tired old battle lines of Australia’s ‘free speech wars’ have once again crept into sporting affairs. The implosions of the week involve two football clubs, Essendon in the AFL and Manly in the NRL, whose years of on-field success are fading from memory and who stumble with equal blindness into a new world that eludes their comprehension and their ability to adjust.

For Essendon and Manly, winning premierships used to be ingrained. It was also enough. Winning was what the clubs were for, it was what they were good at, and they needed to do nothing else to justify their existence. They were the envy of their opponents.

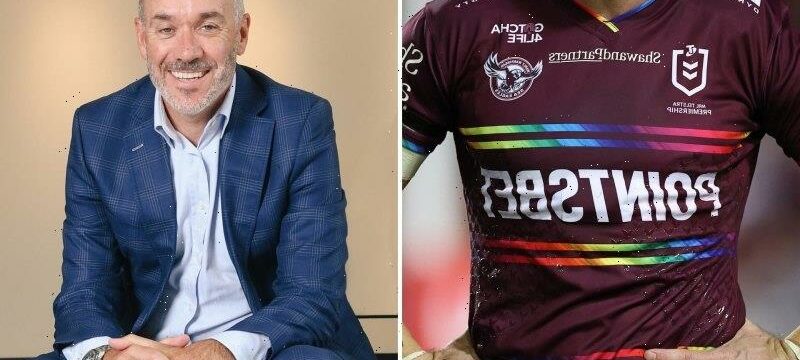

Manly’s controversial pride jersey and former Essendon boss Andrew Thorburn.Credit:Getty/Peter Braig

Years of scandal and management failure at both clubs have recast them as old-world, somehow pre-revolutionary, stranded in their glory days. Overtaken by events, they have tried to play catch-up. In Manly’s case, the most recent attempt to join the 21st century was to paint rainbows beneath the gambling logos on their jersey and hope that half their players wouldn’t notice. They didn’t win another game. In a delicious twist, coach Des Hasler might now sue the club for sabotaging his KPIs and making it harder for him to get a contract extension.

If you couldn’t make that up, even more baroque is the situation at Essendon, where Andrew Thorburn’s resignation after being CEO for a day has earned him more notoriety than his resignation from the National Australia Bank’s top job, presumably because football is something more Australians care about.

Essendon and Manly now provide case studies in how not to do things. ICYMI: Essendon’s previous CEO and chair had fallen on their sword after using it to decapitate the head coach, Ben Rutten, during yet another disastrous season. The Bombers appointed a CEO recruitment panel that included Thorburn, whose exit from banking – when the Hayne Royal Commission exposed a litany of dishonest practices – was of no concern to the Essendon board. Nor did his chairmanship of the City on the Hill Church, a socially conservative evangelical breakaway from the Anglicans, raise any alarm.

The embarrassments will continue while codes and clubs, hoping to buy good karma at a bargain price, remain so haplessly out of their depth.

In due course, the search panel failed to locate a CEO better qualified than Thorburn himself. The board had a brainwave and asked Thorburn to step aside from the panel but not to walk so far out of the room that they couldn’t ask him back in and offer him the job.

The farce, which seemed over, had barely begun. Once Thorburn accepted the job, some bright spark on social media found out that members of his church had said some things that were not a million miles from what was proclaimed from the terraces of CommBank Stadium, this time not in the name of football or Croatia, but in the name of God. (Same thing, really.) Thorburn, who had helped inaugurate the AFL’s pride round when his bank was the code’s major sponsor, did not endorse these extreme views personally, but the club figured it might be awkward for him to have to reconcile some of this uncontrollable holy-rolling with the football league’s strictly policed commitment to diversity and inclusion.

Essendon couldn’t ask Thorburn to choose between his god and his football club – that would be discrimination! – but it could ask him to reconsider whether he could, as chairman of the church, continue taking responsibility for statements that had become as palatable as a fascist salute. Thorburn chose his god, accepted the situation, and a day later – such a long time in football – said he didn’t accept the situation at all. In piled the politicians and the free speech debating clubs. How the hell did all of this get onto the sports pages?

The matter of banning a Nazi from a football ground is straightforward and easy to digest. The Sydney United creep even had his privacy protected, so now he can do his Hitler salute as much as he likes as he watches games from the privacy of whatever cave he crawled out of.

On the other hand, the intersection (call it a five-way pile-up) of religion, free speech, minority rights, virtue signalling and sportswashing are repeatedly coming together in the ugliest public collisions, benefiting precisely no one.

Sydney United fans at the Australia Cup game.Credit:Getty

Was any vulnerable life saved by Manly’s rainbow? Has the Thorburn matter left anyone feeling more included, more safe, at Essendon? As has become the pattern, the residue these incidents leave is the hard fact that professional clubs’ commitment to diversity is still wanting for proof. Gay male footballers are no keener to come out now than they were in the 1980s (when Essendon and Manly were great). Indigenous footballers are still mistreated. Religion divides organisations that have little understanding of practical tolerance. Free expression of individual difference? In football? Don’t make me cry.

The embarrassments will continue while codes and clubs remain so haplessly out of their depth. When they try something nice and virtuous by dipping their toe into identity politics, hoping to buy good karma at a bargain price, they find their foot caught up in a live electrical cable sucking them down into the sporting hell where clubs like Essendon and Manly find themselves. The embarrassments recur because, in their arrogance, the codes still classify ‘inclusion’ as a branding opportunity and keep buying into deep serious human issues without thinking through the consequences.

At the end of their season, football premiers are accused of hubris when they toss out some derisory words about their defeated opponents. But really, what can be more arrogant, what can betray more hubris, than institutions who believe that with little more than a jersey, a logo and a slogan, a themed week and a religious incantation of the word ‘commitment’, they are so powerful that they can lead the real world to a better place?

What other regimes had such delusions as to think that their symbols could remake the world in their image? Surely nothing is more arrogant than a gesture; the more empty it is, the more harm it inflicts.

Sports news, results and expert commentary. Sign up for our Sport newsletter.

Most Viewed in Sport

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article