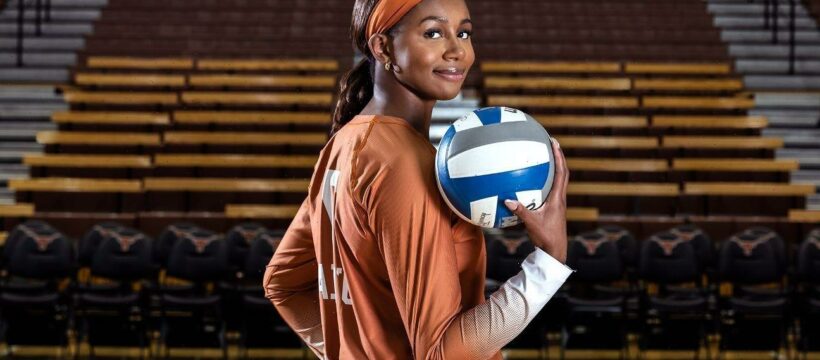

ON A SPRING afternoon in Austin, Texas, Asjia O’Neal nonchalantly walked into the Heart Hospital of Austin for her cardiology appointment, a twice-a-year routine she had been keeping most of her life. She changed into a hospital gown, lay down, and a nurse administered an echocardiogram and an EKG, tests to check the rhythm and structure of her heart and its electrical signals. As she waited on the exam table for her doctor, she made small talk with the Texas volleyball team’s physical trainer, DeAnn Koehler, who had driven her to the hospital. They talked about the weather and the upcoming 2019 season, when O’Neal, a 6-foot-3 middle blocker, would make her debut after redshirting her first season with the Longhorns.

Her doctor entered the room, holding her results in his hands. “There’s been some changes,” he began.

“It’s not safe for you to play volleyball anymore.”

O’Neal’s mitral valve leak — a condition she was born with that redirected blood back into her atrium rather than out to her ventricle, a condition that forced her heart to work extra hard to pump enough blood in the right direction, a condition that she already had undergone one surgery to correct — had gotten worse, the doctor explained. And the intensity of volleyball was putting too much stress on her cardiovascular system. It was too dangerous for O’Neal to continue.

O’Neal tuned out every word that came out of her doctor’s mouth after that. She stared at him blankly, her mouth glued shut. She watched Koehler’s mouth move, but couldn’t process a word of the urgent conversation her trainer was having with her doctor.

A few minutes later, she heard the doctor ask her if she would consider other, less intense, sports. Maybe golf or cricket? She couldn’t bring herself to respond.

In silence, she stood up and walked with Koehler to the car.

When O’Neal arrived back on campus, she called her mom from the sidewalk; Mesha O’Neal heard only sobs. Catching her breath, Asjia narrated how a routine checkup turned into a nightmare.

“We’re going to get a second opinion,” Mesha said forcefully into the phone. “We’re not going to take what one doctor says and run with it, you hear me?”

Asjia hung up and walked in a daze to her dorm room, where her teammates and friends Jhenna Gabriel and Logan Eggleston were waiting.

“How did it go?” they asked.

O’Neal burst into tears once again, holding her face, sobbing and remembering.

At 13, she had undergone an open-heart surgery so she could play the sport she loved at the highest level. But seven years later, just as she was positioned to become an impact player at one of the elite programs, the one thing she wanted to avoid at all costs was staring her right in her face: a life without volleyball.

“We’ll figure this out,” Gabriel said, handing O’Neal a piece of chocolate cake they had brought back from the Longhorns’ last-day-of-spring-training celebration.

It would have been impossible to know then, but that bleak hospital visit actually would be cause for chocolate cake. By identifying that O’Neal’s leaky valve had worsened, the doctor that day started a chain reaction that could lead to celebrations for years to come. His recommendation to walk away from volleyball only strengthened O’Neal’s resolve to stay on the court, prompting Asjia and her family to look hard for alternate solutions. And that would lead to another open-heart surgery and an agonizing rehabilitation. That better-than-ever heart would help shape a more powerful athlete than ever before, one that will give Texas another shot at an elusive third NCAA volleyball championship this month. And that empowered athlete would become an ever more influential person in arenas that matter far more than the Longhorns’ Gregory Gymnasium.

ASJIA O’NEAL HAS always been a regular at big arenas. When she was a toddler, her father, Jermaine O’Neal, was at the peak of his 18-season NBA career. In 2002, two years after Asjia was born, O’Neal was named the league’s most improved player, charming fans with his outgoing personality and tantalizing promise with the Indiana Pacers. He took Asjia with him to most every game, and by the time she walked and talked, she was on TV, in her father’s arms, celebrating his career with him.

Asjia was a “big baby,” Jermaine said, recollecting her birth, when she arrived with a mitral valve leak, which would require regular cardiology appointments and monitoring. But doctors told the O’Neal family that Asjia could lead an otherwise normal life.

She began holding her bottle at 2 months, with “these big hands,” as Jermaine recalled, and walked and talked before she even turned 1, at about 8 months old.

Growing up, she loved watching her father, a six-time All-Star, play basketball. She asked him to train her during the summer after fourth grade, but something didn’t feel right. It didn’t feel like this was her game, like this was what she was meant to do.

Basketball aside, Asjia was like her father in most every way. A day before competing in her fourth-grade spelling bee championship, Asjia ran around their Miami house, performing one-handed cartwheels. Jermaine stopped her and said, “Asjia, you need to settle down and study for the spelling bee if you’re going to have any chance of winning it.” Midway through a cartwheel, Asjia said, “Dad, I’m going to win it.” The next day, she went up on stage and won the title, spelling the word “vegetable” for the championship.

“I had tears in my eyes,” Jermaine said. “I remember just always saying, ‘I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that,’ and Asjia is the spitting image [of me].”

Asjia fell in love with volleyball in 2012 — when she was in seventh grade — after the O’Neals moved to Dallas, where volleyball was a hugely popular sport. During one of her first days at school, two girls asked her if she’d ever thought about playing volleyball. That day, she tried out and made the school’s B team (the school had an A, B and C team). She had a lot to learn — volleyball’s rules were “weird” — but she loved the intensity, the ability to work closely with her teammates when the ball was in the air and the speed of the game.

Even before she knew the game’s nuances, Asjia’s hand-eye coordination was impeccable, and her height — she was 5-10 at age 12 — made her an immediate powerhouse.

Just as she began to feel like this might be her sport, she received some shocking news during a cardiology appointment in Boston: Her mitral valve leak had gotten worse in the past year. The intensity of her volleyball training was the likely cause, her doctors told her parents.

She needed a ring placed around her mitral valve to stop the leakage. At 13, she needed open-heart surgery.

The news sent Jermaine and Mesha into a spiral, but Asjia had a much more direct approach. “Let’s get it over with,” she said.

In March 2013, two months after the unsettling diagnosis, Asjia landed in Boston at the Children’s Hospital for her first open-heart surgery.

“My daughter … has a chance to be one of the best volleyball players in the country,” Jermaine O’Neal told the Boston Herald at the time. “College coaches are already calling about her. She has a leaky valve that’s making her heart work too hard. … I’m positive everything will go well.

“She’s not talking about surgery. Me and her mother are talking about surgery, but she’s talking about volleyball.”

The doctors operated on Asjia for five hours, stopping the leak and then closing her chest. She would need six weeks of rest before she could be cleared to play. And another six weeks of monitoring before her chest bones completely healed.

“She probably would not have had to have it if she did not play sports,” Mesha said. “But because she wanted to play sports, she needed it.”

To Asjia, it’s all a blur now. “I was so young. I remember recovering so quickly and going out there and playing and feeling great.”

As soon as she was cleared to play, she was back on the volleyball court. At age 14, she received her first college letter, from LSU. At 15, when she saw Texas head coach Jerritt Elliott at several of her matches, her excitement grew. She knew of Texas’ success and she wanted to be a part of it. She committed to the Longhorns during her sophomore year.

She had an intuition on the court that amazed coaches.

“I’ve always said, ‘How do you [know]?’ and she’s like, ‘I don’t know, I just know. I just know how to do it, it just happens,'” Mesha said.

She was the definition of athletic, but she had such grace, such fluidity about her.

“She’s a master,” said Ping Cao, Asjia’s club coach.

As her future began to take shape, Asjia thought her medical issues were in the past. Her heart was stronger, it was working better, and she could play the sport she loved.

Little did she know that her chest would be sawed open again. And this time the problem was even worse.

“MOM, SOMETHING IS very wrong. I don’t know if I can do this,” Asjia said to Mesha on the phone after one of her first spring practice sessions during her redshirt freshman year at Texas in 2019.

She had struggled through her first week of training, barely managing to stay on the court. The level at which Texas played was so much higher than what she was used to, but all the other freshmen did it, so why couldn’t she?

Practice lasted four hours, and at least once a week she couldn’t get through it, sometimes feeling so dizzy that she had to be pulled off the court. Any long cardio exercises — running on the treadmill or pedaling — were out of the question. At her peak, she could run 10 minutes before she started to feel light-headed.

She had a congenital heart condition, but she didn’t want to use it as an excuse, so she pushed herself, sometimes to the brink, before Koehler noticed her struggling and made her leave the court.

“She never wanted to accept that her heart [condition] prevented her from doing certain things that other people could easily do,” Mesha said.

Asjia’s echo and EKG results didn’t show anything out of the ordinary, which made her question herself even more.

“[The] doctors, they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s the same as it always has been,'” O’Neal said. “And I’m like, ‘Well, then why do I feel like this?'”

In order to monitor O’Neal’s heart and to compare her to people without a heart condition, her teammates wore heart monitors during practice. The monitors revealed how hard her heart was working to allow her to play.

It was on that last day of spring training that O’Neal’s doctor told her that she shouldn’t play volleyball anymore. The previous tests hadn’t picked up on her deteriorating condition.

The O’Neals immediately sprang to action. Jermaine, who had been diagnosed with an irregular heartbeat in 2013, called every doctor he knew in the NBA to get his daughter the best treatment he could. Three days later they had an appointment booked at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, which has consistently ranked No. 1 in heart care in the U.S. News & World Report’s Best Hospitals rankings. The doctors there came to a consensus — she could play out the 2019 season, but she would have to go in for cardiology appointments every three months in Austin, and the results had to be shared with her doctors at Cleveland Clinic.

In November, just days after the family had sent Asjia’s latest reports to Cleveland Clinic — the evening Texas played Oklahoma — Jermaine received an urgent call from Asjia’s doctor.

Asjia needed to get to Cleveland as soon as possible for an MRI. Her heart condition had deteriorated even further.

“I had no idea, because it was the same protocol — some days I would feel bad, some days I would feel better,” said Asjia, who had a .413 hitting percentage and averaged 1.48 kills per set through the first 19 matches of that 2019 season. “But I thought this might just be the reality of me playing sports.”

When Jermaine told her that they’d have to fly to Cleveland, Asjia’s first reaction was, “Wait, am I going to miss my next game?”

After a day of exhaustive tests, which included injecting dye into her heart to see the direction of the blood flow, and other athletic tests to monitor her heart at the highest exertion levels, her doctors confirmed the O’Neal family’s fears.

She needed to have another open-heart surgery. Her mitral valve leak had worsened, and to add to that, they found a second leak in her tricuspid valve.

“Athletes, when they are exercising, they convert their cardiac output — as we call it — or circulation, they multiply that by at least five times, sometimes more. So instead of the heart pumping at five liters a minute, [it] would be pumping at 20 liters a minute for an athlete,” said Dr. Hani Najm, who performed O’Neal’s surgery. “[Asjia] was not able to perform because her heart was not able to [sustain] at that level.”

As soon as the doctors left the room, Asjia turned to her parents and said, “I just want to finish out the season. It’s literally one more month. Nothing’s going to happen to me.

“I’m not going to just die on the court.”

When they walked into Najm’s office, they asked, almost in unison, “Could she finish the season?”

“Yes, she can finish the season,” Asjia remembered Najm saying. “What she has, she’s had for more than a year now.”

And she did, sticking with her team until the Longhorns lost in the NCAA regionals against Louisville on Dec. 13, when she hit .778 with seven kills and five blocks.

A month after Texas’ season ended, O’Neal walked into Cleveland Clinic in a green dressing gown, ready to have her heart cut open — again.

ON THE MORNING of Jan. 14, 2020, two months before the pandemic shut down the country, O’Neal was wheeled into the operating room, with her parents, her brother, Koehler and coach Elliott by her side. Up until that morning, O’Neal felt in control. I have done this before, and this too shall pass, she kept telling herself. But as the time of the surgery got closer, nervousness hung over her like a heavy blanket. The previous day doctors had told her that recovery would be more difficult this time. She was no longer 13, and they were reopening the same incision and using a bone saw to cut open her chest.

That makes me sick, O’Neal thought.

She hugged her family, her coach and her trainer before getting wheeled away. As she went under, O’Neal remembered hearing “Started from the Bottom,” a song her nurses picked for her when she told them she loved Drake.

O’Neal had outgrown the ring that was placed in her mitral valve during her first open-heart surgery. Dr. Najm replaced it with the “biggest ring” he’s ever “put on a woman before,” Mesha remembered Najm saying. He also stopped the leak in her tricuspid valve. All the while, Asjia was hooked up to a heart-lung machine to keep her blood flowing while her heart was stopped so Najm could repair her valves.

In Asjia’s case, Najm made an unusual decision. Instead of opening up her heart to replace the valve with a prosthetic one, as would be the norm with cases like hers, Najm re-repaired her mitral valve, removing fibrous tissues around the valve before placing the bigger ring.

“I know her lifestyle and her career, and if I replaced her valve with a prosthetic one, she would have to commit to subsequent surgeries,” Najm said. “I also didn’t want her to have to take blood thinners [as an athlete].”

About five hours later he walked out of surgery and said, “It’s a success.”

“I felt that I had produced a good piece of art that is going to last long,” he said. “She will never know how bad she felt until she feels as good as she’s going to feel now.”

When O’Neal awoke, the clock in front of her bed read 10 p.m., and her throat was on fire. She hadn’t had a sip of water in almost a day (doctor’s orders), and she couldn’t for a while longer to prevent fluid buildup in her body. The doctors told her that she would be discharged when she walked around the hospital, once, with a walking aid.

On the first day after the operation, she couldn’t sit up, couldn’t engage her core in any way, and her parents had to sit her up. She had fluid buildup in her chest, something that’s normal post-surgery, but that meant she had to work her core to cough it up.

“They would always try to make me cough things up, but it would hurt so bad to cough because obviously my chest is broken,” O’Neal said.

On the second day, she slowly sat up and walked a few steps with support. The third day, she could walk farther. And on the fourth day, she could make one round, with her aid. The doctors signed her discharge papers.

All along, she was plotting her comeback.

ASJIA O’NEAL LIFTS into the air, but the set by Jhenna Gabriel is tight. She nudges the ball over the net, and the referee blows the whistle. A violation is called. Point Oklahoma. Texas’ lead shrinks to one, 22-21. Just a few minutes ago, the scoreboard read 22-17. Now, it is anybody’s set.

Gregory Gym, which is hosting 4,295 people for this Nov. 11, 2021, encounter against Oklahoma, erupts in boos. A week earlier, Texas had lost its first game of the season to Baylor in Waco, and there’s lingering worry in the air.

O’Neal looks at the official who made the call, her face scrunched up, her palms wide open, What was that about? Elliott, his mask halfway down, walks over to the referee to talk. Then he calls captain Logan Eggleston to run over to question the call.

O’Neal’s right foot had landed on the Sooners’ side of the net as she nudged the ball over. Point Oklahoma.

Asjia’s mother, Mesha, sitting in the bleachers behind the Oklahoma side of the court, says, “She looks upset.” (Mesha has missed only one home game this season, and she sent over her parents to watch her daughter play that day.)

The next point, O’Neal gets a kill on an Oklahoma over-pass. Wearing No. 7, the same number her dad wore for most of his career, she stares at her opponents, her palm wide open, a nonchalant shrug. Her hair blazes behind her as she walks over to her teammates for a high-five. The point after that, O’Neal blocks the Oklahoma attack, 24-21 Texas.

On Texas’ second set point — with the fans on their feet — Gabriel and O’Neal connect on a perfect slide attack, and a smile finally creeps across O’Neal’s face after she gets the set-clinching kill.

“She’s the biggest hype man on the court — you can see every emotion on her face,” Eggleston said. “She brings so much energy to the team and we feed off of her all the time.”

While watching O’Neal on the volleyball court, it is easy to forget that just 22 months ago, she could not sit up, let alone elevate her entire body to make a kill. For six weeks after her surgery, she was home in Dallas, slowly building up her strength. Shortly after she was cleared to return to the gym, the coronavirus pandemic shut down sports. She returned home, working with Koehler remotely to rebuild the soft tissue in her chest. Jermaine had set up a home gym, and she liked training on her own timeline. First she walked on the treadmill, then she jogged, then she jogged on an incline, building her cardiovascular strength. In addition, she built her core strength, and did band work and mobility exercises.

“I had a ton of dialogue with [her doctor], probably even more than she knows,” Jermaine said. “Was there anything that we should be looking out for or pulling her back on?”

“He said, ‘Look, she can go as far as she can take herself, she’s completely fine to push herself.'”

Because O’Neal trained alone at home, it was hard to tell how far she had come in her rehab. But when she returned to campus in July 2020, she could see how she compared to her teammates. She could push herself to run 30 minutes on the treadmill, something she couldn’t dream of doing before surgery. When the team began doing conditioning and agility training in the sand, she was “blowing through it, beating people in races,” O’Neal said. Before the surgery, even a long warm-up exercise — which included yoga postures like downward dog, sugarcane and bow pose — would leave her winded. Now, she could perform the entire routine on resting heart rate.

After her first sand workout that summer, she called her mom crying. “I can’t believe this is how you guys feel all the time,” she said to Mesha. “This is it? I’ve been struggling all this time, and this is how everybody else feels after a workout?”

Said Koehler: “She was playing at a low 60% capacity before the surgery. Now, she’s somewhere in the high 90s.”

Teammates were in awe.

“You just had your whole chest open, and you’re already back,” Gabriel recalled telling O’Neal. “Like it was just — it was crazy.”

O’Neal has become a leader for Texas, the national runner-up to Kentucky a year ago. She didn’t miss a game in 2020, returning to action eight months after surgery and finishing the season with 222 kills and 113 blocks. She brought 152 kills and 95 blocks into this year’s NCAA tournament, and Elliott said the Longhorns will need her in order to end the title drought that dates to 2012. The Longhorns (25-1), who also made it to the NCAA finals in 2015 and 2016, are the No. 2 overall seed and opened the tournament with a sweep of Sacred Heart at home. Next up is Rice (20-6) on Friday.

“She has the ability to change [the team’s] personality, maybe more than anybody on our team,” Elliott said. “She can get pretty feisty, and she can get pretty competitive — and we need that.”

ON A SUNNY November day in Austin, O’Neal, wearing a burnt orange Texas long-sleeve shirt, bandana and black sweats, is seated at an outdoor table at Civil Goat Coffee, one of her favorite cafes. In between bites of her banana and strawberry protein bowl, she shares her story, her hands moving animatedly as she recounts her journey. Mesha is sitting next to her eating a salad, and even though she knows Asjia’s story intimately, she’s paying close attention, nodding at times, and adding her perspective here and there.

As Asjia wraps up the story of her second surgery, she puts down her spoon, her gel manicure (with a white squiggly line design), glinting in the sunlight. She pulls up her shirt and points to three healed holes spaced equidistant below her chest. Three tubes were inserted into the holes during her surgery to help collect fluid buildup that occurs during an open-heart surgery.

On her last day at the hospital, her doctor walked in and said, “This is going to hurt,” as he prepared to remove the tubes. Holding her mother’s hands tight, she remembered how this hurt after her first surgery, and the tubes were bigger this time. She would have to be awake, no anesthesia to numb the pain. She felt the tube leave her body, tears streaming down her face, her chest erupting in pain. After a quick break, the doctor went in again, and then again. O’Neal took a deep breath, her lungs filling up with fresh air, unhindered by the tubes.

After her first surgery, she was hesitant to show her scars to the world. She was a middle schooler and didn’t want to draw attention to her differences. But today, she embraces them, both on her social media and in real life.

“I’m proud of the moment and just coming back from it — so now, I’ll wear whatever. I’m going to show [my scars], I don’t care,” O’Neal said. “I think it’s important to tell my story and acknowledge that it happened. Because of it, I’m better.”

O’Neal’s voice grows louder toward the end of the sentence, like she really wants people to hear her. A fan walks over and interrupts our conversation. “I heard the word ‘volleyball,’ and I just wanted to say hello. I love watching Texas play,” he says.

“Thank you,” she says and smiles politely.

After the death of George Floyd, O’Neal felt a similar need to be heard. She organized meetings with the volleyball staff and her teammates. Things had to change within the University of Texas, and in America, she said. She has a younger brother, and what happened to George Floyd could happen to him. That was unacceptable.

“It was amazing to watch her speak — she didn’t care about hurting anybody’s feelings,” Gabriel said. “She said what needed to be said.”

O’Neal orchestrated the Longhorns’ Black Lives Matter video campaign. “All lives can’t matter, until Black lives matter,” she says in the video, looking directly at the camera.

She surprised herself by not just leading her team in conversations about racial justice, but also taking those conversations to various communities within UT. Her voice helped spark important changes on campus. Robert Lee Moore Hall — named after a mathematician known for his racist treatment of African American students at Texas — was renamed the Physics, Math and Astronomy Building. UT is also erecting a statue of Heman M. Sweatt, the first Black student admitted into the UT Law School, who fought and won a Supreme Court case that paved the way for desegregation at colleges and universities across the country. In addition, UT erected a statue of the Longhorns’ first Black football letterman, Julius Whittier, and it renamed Joe Jamail Field at Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium to Campbell-Williams Field, after Texas’ two Black Heisman Trophy running backs, Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams.

Like many other vocal athletes, O’Neal faced backlash on social media, with comments on her profile like, “I’m never going to buy a ticket again.”

“If that’s how you feel, do what you want with your money,” O’Neal says matter-of-factly. “We have a purpose and that’s what we’re standing by, and if that offends you then you’re entitled to your opinion, but get on the train or get off the train.”

In June, O’Neal received the Honda Inspiration Award, an honor given to student-athletes who have experienced extraordinary physical and/or emotional adversity.

“Asjia is a spitting image of me, but she is better — a much better version of me,” said Jermaine, who went straight from high school to the NBA. “At 22, she is more equipped, she can use her voice to make this world a better place. What she believes in as an African American, Black woman — be powerful about that — speak about it in an educated way. She does that at such a high level, she blows me away. I literally just told her this yesterday, I said, ‘Asjia, you’re special, because you’re much bigger than just a volleyball player.'”

Asjia will play another volleyball season at Texas as she finishes her master’s degree in sport management (she finished her undergraduate degree in corporate communications in three years). Then she wants to play professionally overseas. But more important than anything, she wants to inspire young girls — young Black girls — that anything is possible. She receives messages from Black mothers on social media talking about how their kids want to play volleyball after watching her on the court.

“Seeing little girls come up to me and they’re not just of one background, not just white girls, and they’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so inspired to be you. I love your team. I love seeing people that look like you,’ That’s so important,” O’Neal said.

“Regardless of my accomplishments on the court, I think just having that imagery for young girls is incredible.”

The weekend before Texas took on Oklahoma, the O’Neals were in Waco to watch Asjia play Baylor. As Jermaine sat in the bleachers, he scanned the crowd — posters carrying Asjia’s face and her jersey number peppered the stands. Two families who traveled from Indianapolis and Kansas City introduced themselves to Jermaine. One of the parents said, “We flew down here just to see your daughter.” It was important for their daughters to watch Asjia play.

“All the hard days and hard nights to be put in that position … that’s special,” Jermaine said.

Her father put it mildly. More viscerally, Asjia was willing to open her heart — twice — to ensure that.

Source: Read Full Article