This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

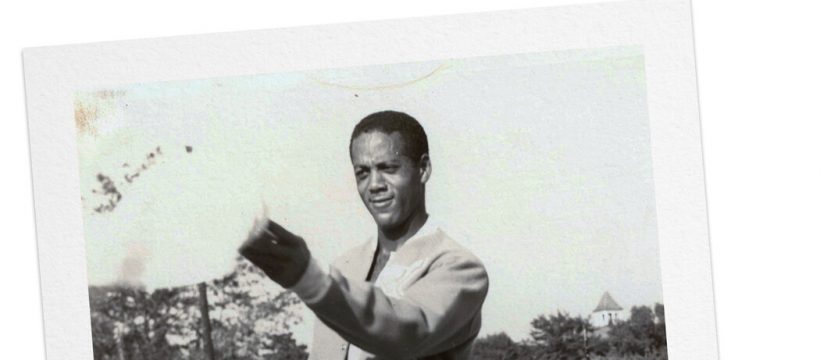

In the pantheon of great Black tennis players — Serena and Venus Williams, Arthur Ashe, Althea Gibson and so many others — Jimmie McDaniel undoubtedly has a place, having preceded the others in breaking the sport’s color barrier. Yet mention of his name would undoubtedly elicit blank stares from tennis cognoscenti worldwide — the curse of a man ignored in the history of a sport that was, during his time, overwhelmingly rich and white.

More than 80 years ago McDaniel played what is believed to have been the first interracial tennis match, against the world champion, Don Budge.

The match, on July 29, 1940, was referred to as “the most important sports and social event to hit Harlem in many years” by The Amsterdam News, the country’s leading Black newspaper at the time.

It was 10 years before Gibson first played at Forest Hills, seven years before Jackie Robinson became the first African-American player in modern major league baseball and 14 years before Brown v. Board of Education declared that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional.

On that day, McDaniel and Budge faced off before a crowd of more than 2,000 people who packed the stands, covering every inch of the court’s perimeter. Hundreds more cheered wildly from apartment windows, rooftops and fire escapes nearby.

Two years earlier, Budge had become the first winner of the coveted Grand Slam by capturing singles titles at the Australian, French, Wimbledon and United States championships. McDaniel, a collegiate superstar talented in multiple sports, was regarded as the best African-American player of his time.

Budge’s sponsor, Wilson Sporting Goods, arranged for the match at the Cosmopolitan tennis club, the headquarters of the American Tennis Association, the only league at the time that welcomed all races. While the match was seen by some as a publicity stunt, others noted that Budge had crossed the color barrier by coming to Harlem. The prominent sportswriter Al Laney, covering the match for The New York Herald Tribune, praised Budge for “performing an important service for the good of the game.”

Though McDaniel’s powerful left-handed kick serve could send opponents diving into the courtside fence to retrieve it, he had never seen anything like Budge’s famed one-handed backhand. McDaniel also got lost on his way to the club that day and arrived only minutes before the start of the match. He was so nervous that he double-faulted 13 times and lost the match, 6-1, 6-2.

“I remember getting thoroughly waxed,” McDaniel told World Tennis magazine in 1979. “He hit a backhand so hard it dug a hole in the clay. I turned around and said to my coach, ‘What do I do with that?’ It was like going from the bush leagues to the majors.”

Budge saw the match differently. He told reporters afterward, “All he needs is a little more practice against men of our caliber and I’m convinced that he will have a good chance of being one of the best players in America.”

Some see the match as a seminal moment in sports history.

“The Jimmie McDaniel-Don Budge match was critical as much for white America as it was for Black America,” Dale Caldwell, the founder of the Black Tennis Hall of Fame, said in the 2007 documentary “Breaking the Barriers.”

While Budge had proved his prowess, there was no way for him to know for sure that he was the best player in the world as long as the sport was segregated. “I think that’s one of the reasons he was willing to come to our home and play Jimmie, who was the best in the Black community,” Caldwell said.

James Pierce McDaniel was born on Sept. 4, 1916, in Greenville, Ala., about 50 miles south of Montgomery. His father, Willis, was a professional baseball player in the old Negro leagues and passed his athleticism on to his son.

After his baseball career ended, Willis moved the family to Los Angeles, where he became a railroad porter. When he died, his wife, Ruby (Harrison) McDaniel, was left to care for their seven young children. She worked as a domestic six days a week to put food on the table.

Jimmie picked up tennis in elementary school, hitting balls against a backboard or practicing on the school’s sole dirt court. He never had a lesson and never played a junior tournament. At Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, he focused on track and field until his senior year, when he joined the previously all-white tennis team and led it to the league championship.

In 1935, McDaniel played a practice match against a fellow Los Angeles high school student named Bobby Riggs, who was then the top-ranked junior player in the country, and who would go on to win Wimbledon in 1939 and the U.S. Nationals in 1939 and 1941. (He is best remembered for losing to Billie Jean King in what was billed as the “Battle of the Sexes,” at the Houston Astrodome in 1973.) McDaniel lost, 7-5, 13-11, in the hotly contested battle, but according to his son, Kenneth, it wasn’t a fair fight.

“My uncle Al told me that Riggs was cheating Daddy that day,” Kenneth McDaniel, now 74, said in a phone interview, “but my father was too quiet and too polite to argue.”

There was a reporter there who saw the whole thing but, the story goes, said, “If I write this, I’ll get fired.”

When he was 18, McDaniel fell in love with a 15-year-old white classmate, and she became pregnant. For his transgression, he was forced to spend a year in a reformatory and was banned from returning to Southern California for an additional year. But his passion for tennis never waned.

In 1938, at age 22, McDaniel was awarded a track scholarship to Xavier University in New Orleans — he was a powerful runner who had once leapt 6 feet 4 ½ inches to win the Southern California scholastic high-jump title — but he quickly found his way to the tennis courts instead.

Jim Crow laws prohibited Black players from competing at all-white clubs. But the American Tennis Association, founded in 1916 by a group of African-American businessmen, doctors and college professors, allowed McDaniel and countless others to compete at tournaments that were mostly held at historically Black colleges like Tuskegee and Hampton.

By 1939, there were some 150 African-American tennis clubs catering to 28,000 players, according to Sundiata Djata, author of the book “Blacks at the Net” (2006).

McDaniel would go on to win the A.T.A. national championships four times between 1939 and 1946. From 1939 to 1941, he entered 43 A.T.A. tournaments and won 38 of them. He won the national Black intercollegiate singles championship three times, as well as the doubles title in 1939 with his Xavier teammate Richard Cohen.

McDaniel was so intent on perfecting his skills, his son said, that he used to practice his volleying against a wall in the family living room even though the severe pounding would cause dishes to fall and break.

He competed in tournaments for another decade but often faced discrimination. Sometimes he was denied entry into the draw; at other times he was given incorrect directions to the club so that he would arrive late and be forced to forfeit his match.

“The impact of Jimmie McDaniel is critical,” said Katrina Adams, a former tour player who served as the first Black president of the United States Tennis Association. “The kids coming up behind him need to know what he was capable of doing if he hadn’t been denied opportunities.”

With no way to move up in the sport, McDaniel quit, taking up golf and later bowling.

After World War II broke out, McDaniel returned to Los Angeles and went to work at the Lockheed aircraft plant. He began as a janitor and retired 30 years later as a line supervisor.

McDaniel married Audrey Williams, a middle school math teacher, in 1940; they divorced in 1954, and she died in 1981. Their five children — Jimmie Jr., Rosalind, Willis, Kenneth and Audrey — lived with their mother, only seeing their father three or four times a year. Jimmie’s marriage to Dorothy Adams lasted until she died of a brain aneurysm. In 1977, he married Eastlynn Clark; she died in 2009.

Years later, after his retirement from Lockheed, McDaniel returned to tennis, which by then was fully integrated, and earned a Top 20 senior ranking. He also gave lessons to adults and children.

He died of pneumonia in Los Angeles on March 8, 1990. He was 73.

He was inducted posthumously into the Black Tennis Hall of Fame in 2009. But because he had never been allowed to compete against the best, he became a forgotten footnote of the game’s storied past. Art Carrington, the A.T.A.’s longtime historian, has spent decades trying to document and resurrect McDaniel’s achievements.

“People should know that Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe didn’t just pop out of the sky,” Carrington said. “Before them, there was Jimmie McDaniel.”

Source: Read Full Article