By Stephanie Bunbury

Right now, an enterprising gallery space on The Strand in London is capitalising on the love for Wes Anderson’s latest film, The French Dispatch, with an exhibition of – well, what exactly? There are meticulously executed miniature sets, including the printing press that churns out the eponymous magazine. There is a full-scale newsstand straight from Godard’s Breathless (1960) and a few costumes: a red suit worn by Frances McDormand as a hard-nosed news reporter mixing it with the young revolutionaries of 1968; the chiffon gown in which Tilda Swinton’s absurdly coiffed art critic delivers her lectures.

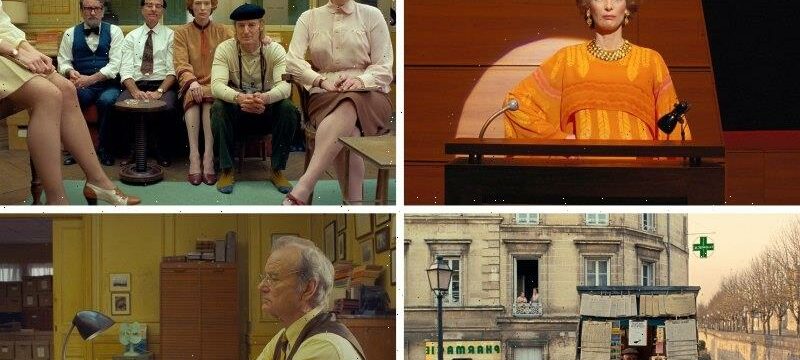

Tilda Swinton at the lecturn in The French Dispatch.Credit:AP

Mostly, however, there are props. I want to call this memorabilia, but it isn’t remembered: this is stuff from a film completed less than two years ago, after all. Stuff. The stuff includes pre-war leather camera cases and a foghorn so ancient it may hail from the previous war, a transistor radio from the ’60s, a salt shaker with a dachshund’s head that could come from the ’30s.

The desk where Bill Murray sits as the editor of The French Dispatch, Arthur Howitzer, jnr, is placed next to a board covered in file cards attached with pins. We’re in a time before Post-it notes, presumably, but it doesn’t have to be specific. This is about imaginative memory, where nothing stands out as anachronistic because everything fits the vision. The unifying factor is that these are all things Wes Anderson likes.

Bill Murray plays editor Arthur Howitzer jnr in The French Dispatch.Credit:AP

The magazine in The French Dispatch is modelled on The New Yorker, right down to the typeface; the film ends with a list of contributors’ names that is both a tribute and a reading list. The New Yorker is something Wes Anderson likes immensely. He grew up in Houston, Texas; his father worked in advertising and his mother sold real estate. He discovered The New Yorker in the library at his school – the same private school he would eventually mine for irony in his film Rushmore (1998) – and was attracted by the fact they had drawings on the covers. He read one and was hooked.

The magazine’s sensibility, which remains unique, was a blast from another life – metropolitan, cultivated, internationalist, intellectually inclined – although, as an aspiring writer, he always read the fiction first. A couple of years later, while he was at university in Austin and a confirmed subscriber, he found out that the University of California at Berkeley was selling off bound copies of the magazine going back 40 years. He bought them all for $US600 – a bargain 30 years ago, maybe, but a hefty sum for a student.

The film had two other reasons for being, Anderson said in a recent interview with the magazine itself. He wanted to make a film about The New Yorker; quite independently of that fact, he also wanted to make an omnibus film with linked but separate stories, which combined fortuitously with the idea of a magazine carrying long features; he also wanted to make a film in France.

Many of The New Yorker’s writers had lived in Paris, of course, as Anderson himself has done for several years. “In Paris, any time I walk down a street I don’t know well, it’s like going to the movies,” he told his interviewer. “It’s just entertaining. There’s also a sort of isolation living abroad, which can be good, or it can be bad. It can be lonely, certainly. But you’re also always on a kind of adventure, which can be inspiring.” Along with everything else, The French Dispatch is about the experience of expatriation.

Robert Musgrave, Owen Wilson and Luke Wilson in Bottle Rocket.

“World-building” is currently a vogue filmic term, probably thanks to a trickle effect from game design. But Anderson has been building worlds, imaginatively and literally, for decades; all his films have been set in an undefinable elsewhere, right back to the flat suburban parallel universe of Bottle Rocket (1996). That was his first feature, about a hapless band of would-be thieves led, as now seems inevitable, by Owen Wilson, who also co-wrote the script.

Ralph Fiennes, centre, amid the shabby glamour of The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The bigger the budget, the more detailed and delirious the worlds he has been able to construct. The faded Edwardian New York interiors of The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) and dream train chuffing through India in The Darjeeling Limited (2007) were remarkable, but The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) dialled up his favoured shabby glamour to a new level.

With its four adjacent stories, The French Dispatch is four times as elaborate, particularly given some of the set requirements: a barricaded street with the cobblestones torn up for the 1968 riots, for example.

Filming took place in Angouleme in south-west France. According to The New York Times, Anderson was looking for somewhere that looked like Paris, but a Paris that no longer exists outside vintage films such as The Red Balloon (1956), “with nooks and crannies, corridors, passages, staircases, layers and ramparts”, to quote producer Jeremy Dawson. Sets constructed around the nooks and crannies made possible Anderson’s signature symmetrical framings. Shots of the real buildings were also merged digitally with miniatures like the one included in the exhibition, which turns an Angouleme street into a Gothic pile, stripped of anything even faintly modern.

Wes Anderson chose Angouleme in south-west France to recreate the sense of a Paris that no longer exists. Credit:AP

Of course, nobody would believe that a magazine like The New Yorker could be published firstly in Kansas – supposedly, The French Dispatch is an expat spin-off from a magazine beloved of corn farmers – still less in a French provincial city. The city is called Ennui-sur-Blase, a very Wes Anderson kind of not-quite-pun. Many of the writers themselves do ring true: Howitzer is a blend of the magazine’s irascible first editor, Harold Ross, and his gentlemanly successor, William Shawn, while Frances McDormand’s reportage on the 1968 student revolts quotes directly from her real-life referent, Mavis Gallant.

But a cycling correspondent? That’s Owen Wilson, Anderson’s old college roommate, who has worked on eight of his films and happens to like cycling. And while The New Yorker has certainly always had a restaurant critic – here played by Jeffrey Wright as a combination of A. J. Liebling and James Baldwin – not one of them has ever been involved in a police kidnapping that includes Saoirse Ronan being locked in a pantry.

Tilda Swinton and Wes Anderson at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.Credit:Getty Images

“You aren’t really dealing with reality,” says Tilda Swinton, who is about to make her fifth film with Anderson, at a press meeting in Cannes. “You are dealing with a cine-fantasy – and he is so cine-literate there is a lexicon of images to draw on.”

Benicio Del Toro, who plays an inmate of a prison for the criminally insane and outsider artist, the subject of a French Dispatch story, remembers Anderson pressing Jean Renoir’s Boudu Saved From Drowning (1932) into his hand, telling him to channel Michel Simon’s suicidal tramp. During the shoot, Anderson would leave a little pile of DVDs outside the hotel dining room for cast and crew: reference material.

The dining room itself has significance. Group meals form the central pillar of another world Anderson creates: his travelling show. He always shoots in a single, preferably isolated location, with everyone in the same hotel and gathering for dinner like a theatre troupe. Many of the cast are regulars. Bill Murray has made 10 films with Anderson. Despite playing the pivotal role in the French Dispatch ensemble, he reportedly ensured – as he always does – that all his scenes could be done in a couple of days. Then he stayed in Angouleme for a week.

There is some indication of how unusual this atmosphere is in Del Toro’s admission that, as a newcomer to Wes World, he didn’t know at first when he could leave the dinner table. “I ate and waited till everybody started to go. I go, ‘Wes, it’s midnight, I have to get up at six!’ He said, ‘You can leave at any time’. After that I loved it.”

From left, Elisabeth Moss, Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton, Fisher Stevens and Griffin Dunne in a scene from The French Dispatch. Credit:AP

That sense of being a company also supports Anderson’s filmmaking style, which demands actors co-ordinate as tightly as a Broadway chorus line. “So much is unique,” says Adrien Brody, whose role as an art dealer is his fourth in a Wes Anderson film. “Technically, most films cover each shot with close-ups and coverage, so you can cut around performance and timing in the editing room. What Wes creates is this choreography where you are interacting with very specific timing, while you also have this volume of words to get across. Three other actors perform and then the camera swoops to me and I have to nail it, or I’ve dropped the ball for everyone else. This is an enormous challenge, but a great thrill. We have to hold each other up.”

“The thing is,” says Swinton, “that the film is in his head. For some filmmakers, that is not true. Some filmmakers have to see what they don’t want to figure out what they do. Or they work it out in conversation, which is a very beautiful way of working too. But Wes has a sort of – I was going to say disease, but it’s an issue. It’s in there and he has to pull it out of his ear. He has to be able to say, ‘OK, it’s coming now. Benicio, can you take this bit; Adrien, you take that. I need your help because I can’t get it out myself, but it’s in there’.”

Talk about world-building. The entirety of Wes Anderson’s world, the rhythm of every speech and the patina of every prop, arrives fully formed, probably down to the last pin in the last file card, as the film begins. The exhibition – the stuff – is just the leftovers. “It must be mental, having a brain like that,” says Swinton, fondly. Brody agrees. “It must be an enormous amount of work.”

The French Dispatch is in cinemas from December 9.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article