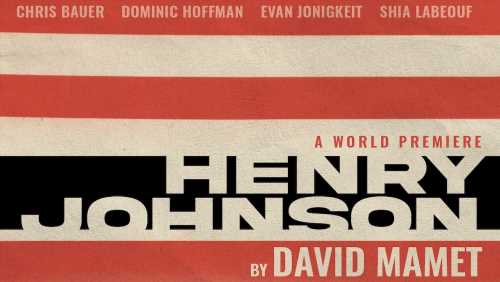

Shia LaBeouf doesn’t appear until more than 20 minutes into “Henry Johnson,” a new David Mamet play making its world premiere at the Electric Lodge in Venice, Calif. The play amounts to just four scenes, barely more than an hour in all (plus an unnecessary 15-minute intermission). LaBeouf is on stage for just two of them, but the instant the film star materializes, something electric happens. The whole audience leans forward.

Maybe it’s the way LaBeouf delivers his lines, mumbling slightly. That’s a tell that he’s on a different wavelength from the three other actors in the cast, who articulate every word of Mamet’s script. But LaBeouf is bringing more to the text. The character — or maybe it’s the performer — seems tortured and slightly volatile. (Who knows how he might react if a cell phone went off in the room?) There’s a delicious unpredictability to what LaBeouf is doing. Whether it fits what Mamet had in mind, I found myself mesmerized to be witnessing such commitment applied to a secondary role in a previously unproduced play, which Mamet evidently dusted off as a favor to the venue.

LaBeouf isn’t even the title character in “Henry Johnson.” That fellow is played by Mamet’s son-in-law, Evan Jonigkeit, and could be described as a patsy, a stooge or, in the Mametian parlance of “House of Games,” a mark. A college boy of negotiable morals and no strong principles, Henry is someone easily manipulated by stronger personalities, and the play, as directed by Marja-Lewis Ryan (“The L Word: Generation Q”), amounts to an exploration of that tendency at a time when entire segments of the country are being swayed — though I suspect Mamet penned it many moons ago.

But human nature remains human nature, and prison gives men time to wax philosophical — and it’s in prison that LaBeouf shows up as Henry’s cellmate, Gene. But first, these’s a crackling first scene between white-collar Henry and his boss, Mr. Barnes (Chris Bauer, who’s done Mamet before for the Atlantic Theater Company). Henry hasn’t yet been arrested. He’s angling to help an old friend from school, but Barnes is several steps ahead of him, leading Henry though a disturbing series of questions.

It seems Henry’s pal — a womanizer he finds admirable, if not downright attractive — impregnated a woman, urged her to abort, and when she refused, induced her to miscarry. It’s an unusually extreme crime to introduce and then move on from, and it surely means something that Mamet (whose work is branded as misogynistic by many) should raise so unforgivable an act and then reveal that Henry was ready to forgive it, thereby landing himself in prison.

“Everyone comes in here worried about getting raped,” LaBeouf tells the schmuck, who’s now sharing his cell, looking dazed as Dorothy to find himself in the clink. “They’re going to sodomize me, or in English, they’re going to fuck me up the ass, and how bad would that be?” That line gets an easy laugh, though Mamet’s script isn’t lazy. It’s short, yes, but the playwright of “American Buffalo” and “Glengarry Glen Ross” reminds us how satisfying it is to know nothing about a group of total strangers and to have them reveal themselves through dialogue.

Gene does most of the talking in the next two scenes, laying out his cynical take on the world, of men and women, and the inequity of it all. “Laws exist to celebrate a lie,” Gene opines, “that people are just.” It’s easy to imagine a different actor bellowing these lines, but LaBeouf delivers them quietly, practically under his breath, while doing all sorts of other business with his hands.

Gene rolls a cigarette, then stoops down to collect the tobacco that’s fallen to the floor. He hides his contraband in a hollowed-out journal, wraps something else in a sock and stashes it under his mattress. He lifts his shirt to rub deodorant on his pits, revealing a chest full of tattoos (the actor got himself inked for “The Tax Collector”). These are small actions, but they reveal the soft-spoken character to be a restless animal. Watching him, I’m reminded of Toshiro Mifune, who could upstage anyone by twitching at the right moment. Not many actors warrant comparison to Toshiro Mifune.

In their first scene together, Gene does Henry a favor. He gets him a job in the prison library. The next scene picks up weeks later, maybe more. Henry has learned that his sentence has been extended. He’s hit it off with the prison doctor, a woman referred to but never seen. In what’s now become an identifiable pattern, Gene questions her motives in flirting with Henry, much as Barnes did the baby-killer’s reasons for reaching out to Henry before. What Henry doesn’t realize (and this is a credit to Jonigkeit’s capacity to tap into the character’s desperate-to-be-liked naivete), is that Gene is manipulating him with a wholly original plan to smuggle a gun into their cell.

The play’s entirely too short to justify taking an intermission after 50 minutes, but so it goes. When the audience returns, the prison library has been turned upside down. There are bullet holes on the window, and Gene is gone. For good. Henry has been played. As Gene told him earlier, “Here’s the wisdom: Everything’s as it seems, all right? All cards are in the deck. It just depends on how you cut them.”

The fourth and final scene plays out between Henry and a guard named Jerry (Dominic Hoffman), whom he’s taken hostage. Jerry’s mission is to make it out of the situation alive, and Henry’s trouble is that he doesn’t learn. He’s a sucker. Jerry tells stories, but he doesn’t captivate us the way Gene did. LaBeouf’s presence is missed. Mamet has already decided how the play will end. It could be longer (there’s room to polish and expand, should anyone else want to perform the show), but anything more amounts to a form of stalling for the inevitable. The thing about men like Henry Johnson is they allow others to decide their fates.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article