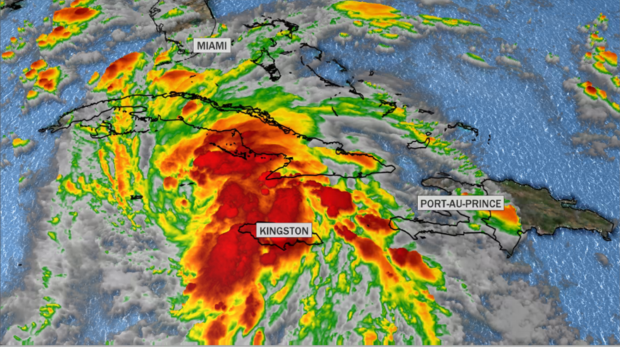

Tropical Storm Ida formed on Thursday evening in the Caribbean, near the Cayman Islands. All indications suggest that Ida will organize and intensify quickly, reaching the Gulf Coast near Louisiana on Sunday as a powerful hurricane — leaving residents little time to prepare.

The system is likely to undergo rapid intensification — an increase in wind speed of 35 mph or more in 24 hours — as it moves across the hot Gulf of Mexico waters, and will probably still be strengthening as it makes landfall. The latest track brings it very close to southeast Louisiana and New Orleans as early as Sunday, arriving from a very dangerous angle to the coast.

Ida is already ahead of schedule. Forecasters at the National Hurricane Center expected the system to form into a named storm later Friday into the weekend. Instead, Ida quickly gained a circulation, ample organization and strong enough wind speeds to be named earlier than expected.

Despite that fact that it just developed, a look at the satellite view above shows that banding is already visible, indicative of a decently organized system.

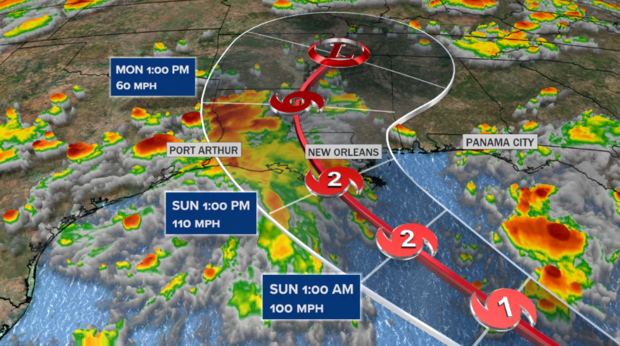

The National Hurricane Center forecasts Ida to move into the Gulf of Mexico on Saturday morning, then to become a hurricane and move northwestward until it reaches the northern Gulf Coast on Sunday. The forecast cone indicates possible landfall between Port Arthur, Texas, and Biloxi, Mississippi, with an emphasis on the Louisiana coast. This could still change, but the models generally agree on this track.

Ida is currently forecasted to be a strong Category 2 at landfall. But forecasters always recommend that residents be prepared for one category above the forecast intensity.

In this case, there’s very good reason for that. Besides the fact that intensity forecasting is very difficult and often off by large margins, this system is working with an extremely conducive environment for intensification. The only thing working against it is time — it’s moving fast enough that it only has about 60 hours to strengthen before it makes landfall.

Ida is currently experiencing some moderate upper-level wind shear, disrupting its circulation. That will lessen on Saturday once the storm reaches the Gulf.

In the tweet below, the upper level pattern is shown with the storm in the center. It illustrates the storm developing a cocoon of sorts around itself — meteorologists call it an envelope — which protects it from outside influence. The blue colors that develop around the storm in a broad circle mark the edge of the protective envelope. The storm creates a protective bubble, like an incubator, that helps it intensify.

High above 99L – as it gets better formed over the Gulf – a protective cocoon (upper level ridge/ outflow) develops fending off wind shear and allowing it to breathe as its envelope expands. Given this, and the very warm water all along it’s path, watch for rapid intensification. pic.twitter.com/UOpt7rntQO

That point may seem a bit technical — but the rest is simple: The storm will also be traveling over a few areas of very hot water, which acts like high octane to fuel to supercharge storms.

In the Caribbean, Ida will move across extremely high ocean heat content, which is hot water that extends to a great depth. Then, when the system reaches the central Gulf of Mexico, it will move over the infamous Loop Current: a curved current of some of the most energy-intensive water in the Gulf. Lastly, as it nears the northern Gulf Coast, it will move over surface waters that are like bath water — 88 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit — some of the hottest surface waters available.

With all this in mind, there’s every reason to believe this will rapidly intensify and possibly become a major hurricane before landfall. A major hurricane is a Category 3 or above.

A strengthening storm at landfall produces much more damage than a weakening storm, assuming an apples to apples comparison with similar wind speeds — and it’s likely the storm will still be intensifying as it reaches the coast.

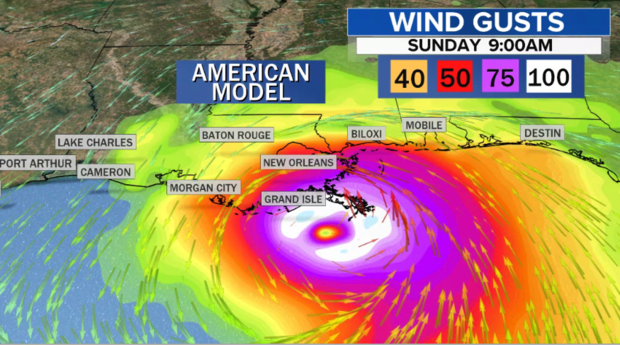

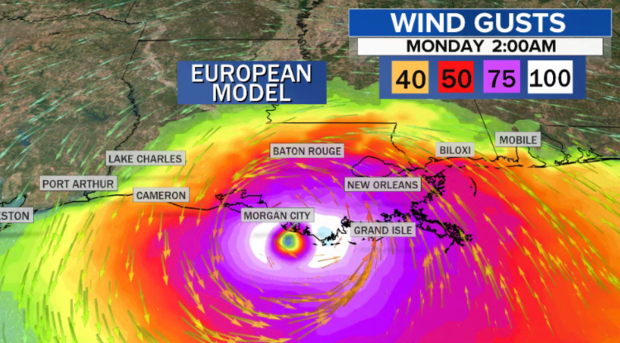

But the devil is in the details. Each model has a slightly different answer when it comes to track, intensity and timing. Pictured below are both the European model and American models. Both show strong storms, but the European is slower and further west. The further east track near New Orleans is problematic for two reasons: the storm would make a more direct impact on the city, and it would arrive faster, allowing less time for preparation.

As the images above show, gusts over 100 mph are likely near the landfall location. The angle of approach will also cause onshore winds from the southeast, piling up water onto the coast. This kind of storm — approaching from this angle, in this area — often creates overachieving storm surge. While it’s too early to forecast exact numbers, there’s no reason to think that surge above 10 feet won’t be possible.

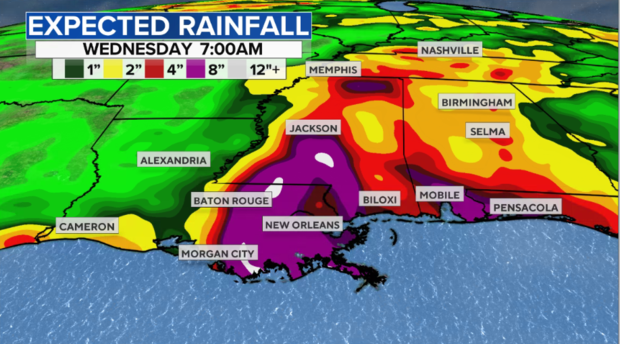

Lastly, the system is carrying lots of tropical moisture, and it will likely slow down once it moves onshore. Along and to the east of the path, rain totals over a foot will be possible. Couple this with saturated ground from well above normal rainfall over the past 90 days, and there will be serious flooding concerns.

Since there is limited time to prepare, anyone in the path of Ida should immediately take precautions. That means making sure your hurricane safety kit is stocked up and you have a plan laid out for your family. Time will be limited to make last minute preparations, so start as early as possible.

Source: Read Full Article