DR MAX PEMBERTON: As Oxford says it will let Kate Beckinsale finish her degree, it’s never too late to revisit youthful dreams

- Kate Beckinsale is considering completing her degree at Oxford University

- Model dropped out of her French and Russian literature studies 26 years ago

- Dr Max Pemberton says learning is good for protecting the brain against atrophy

Have you got unfinished business? Something you started and then, well, life happened and you never got round to finishing? When we look back at the vista of our lives, most of us have ends that aren’t quite tied up, opportunities we didn’t take or mistakes we really should correct. Actress and model Kate Beckinsale is no different.

Last week, she said she’s considering going back to Oxford University to complete her degree, 26 years after dropping out. She had enrolled at New College to read French and Russian literature but dropped out in her second year, aged 22, as a fellow student and friend had died in a tragic accident.

‘My friends were party people and I wasn’t. They’d all moved into a house and I stayed in the college, where I then got mono [glandular fever] and went home,’ she explained. ‘While I was home, one of my dear friends there ended up jumping out of a window and dying.’

She never went back, and assumed her chance of completing her degree was long over. But when she recently returned to Oxford to show her daughter around, her old tutor was still there and said she could return if she wished.

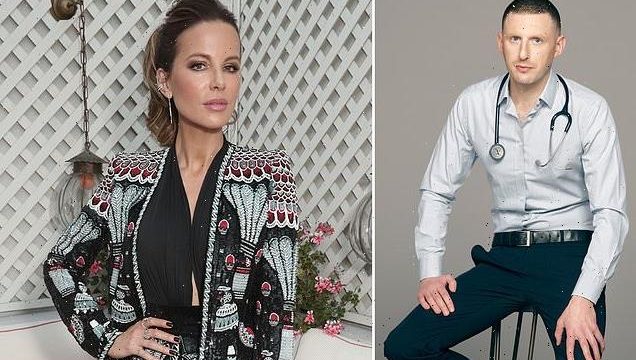

Kate Beckinsale (pictured) is considering returning to Oxford University to complete her degree 26 years after dropping out

There is something to be said for going back and finishing things off like this, rather than simply wishing you’d acted differently the first time round. With the benefit of hindsight, we might regret not completing something, though, at the time, it seemed like we ought to drop it.

A friend of mine always regretted not getting his grade eight piano. He felt incredibly frustrated with himself that, having spent so long mastering the instrument, in his mid-teens he decided he was more interested in girls and going out with mates than in sitting down for hours to practise Beethoven.

After he got married and settled down, he realised he’d made a mistake. Over the years he’s often bemoaned the fact that he got so close to completing all his grades but never did. He wanted that sense of accomplishment, and smarted at the idea that he’d given up when things got tough.

In reality, like for Kate, life just got in the way — he’d changed school and wanted to make new friends, so he didn’t fancy the isolation that comes with hours spent practising the piano. But in middle age, he saw things with a new clarity and wanted to know he could do what had been left undone.

There is something very satisfying about tidying up loose ends in this way. It’s also a powerful reminder that you can take control and make changes.

The brain does get smaller as we age — most adults lose five per cent of volume per decade after the age of 35 — but where once we thought its ability to acquire new skills and remodel itself also declined steeply, now we know that it is capable of great feats of learning well into old age. It might take longer and feel harder, but it’s also very good for us.

Learning something new in midlife sets up a virtuous circle. The more demands we make on our brain, the more we protect it against atrophy, and the easier it is to learn yet more.

Curiosity, and remaining open to new challenges, situations and people, correlates highly with good health and long life.

Dr Max Pemberton (pictured) said learning is good for protecting the brain against atrophy, and the easier it is to learn yet more

So, 25 years after he gave up the piano, my friend bought one and started lessons. After 18 months, and just before lockdown, he finally got his grade eight.

He got up at 4.30am every day to practise for 90 minutes before his children got up, and it was horrible and gruelling. But now he says it’s given him an even greater sense of achievement.

I’ve just done this myself. Many years ago I started training in old-age psychiatry, but got sidetracked.

I had always wanted to work in this area — indeed, I had applied to medical school specifically because I wanted to work with older people and specialise in dementia. As a junior doctor, a professor had taken me under his wing and mentored me.

But then, suddenly, he had to take early retirement on health grounds. I missed his support and direction, and drifted for a bit before picking another area of interest — eating disorders.

I had a hugely enjoyable career in this area of medicine, but there was always a part of me that regretted not completing my training in old-age psychiatry. It was a little niggling thought in the back of my mind — something not quite ticked off.

The pandemic meant I was put on a Covid ward where I was working with older people, and initially I was wistful that I’d given up this dream. But then it occurred to me that there was nothing stopping me from going back and finishing my training.

One evening during lockdown, I filled in an application form and became a (rather old) junior doctor again. On Wednesday I start work in a memory service ward for those with dementia.

We all have things that are unfinished in life. Sometimes it’s good to just give them up, focus on the future and let sleeping dogs lie. But there are other times when, for our own satisfaction and sense of completion, we should go back.

Don’t panic, the kids are all right

Acclaimed children’s author Michael Morpurgo has rather dramatically said that children will never recover from missing their friends over the past year. Actually, I’m not so sure. Certainly children can be damaged by adverse events, and I’ve long been worried about the effects lockdown could have on the poorest. I also worry about those who have been locked up with abusive or neglectful parents and for whom school was a welcome refuge. But most children will bounce back. They soon adapted to lockdown, and while they might not have seen their friends, they will have spent longer with their parents and siblings. Many will have had more time and attention lavished on them by being at home than they would have done at school, too. Studies of children in adverse situations show they are surprisingly resilient, providing they have a stable, secure base, understand what’s happening and feel loved and protected.

Amanda Pritchard (pictured) has taken over as the new boss of the NHS, following the work of Sir Simon Stevens

- The NHS has a new boss. Amanda Pritchard took over the post at the weekend from Sir Simon Stevens. She has big boots to fill — I had great respect for Sir Simon and thought he did an excellent job. Running an organisation as big and unwieldy as the NHS is a formidable task, yet each time I met him he seemed to really care about what was happening on the ground and always wanted to know how, from a clinician’s perspective, things could be improved. I hope Amanda will continue in this vein and listen to those at the coalface.

Dr Max prescribes…

red peppers

Research newly published in the journal Neurology showed that people who consume the most flavonoids — found in brightly coloured fruit and vegetables such as red peppers — are less likely to suffer cognitive decline in later life. Flavonoids protect plants from stress and UV light, but emerging evidence shows they are highly beneficial for human health, including for protecting memory and thinking.

Source: Read Full Article