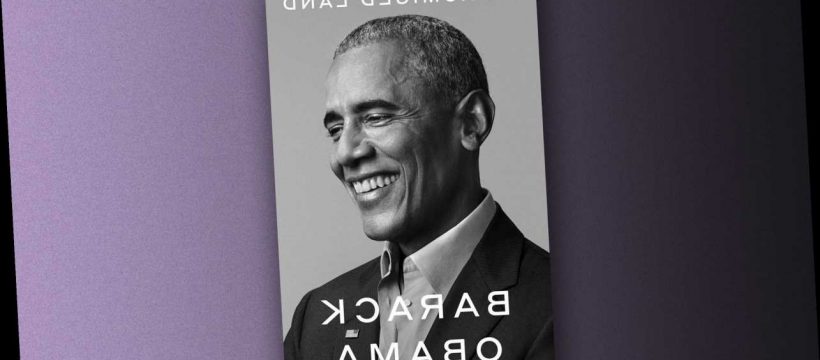

On Monday, The New York Times named Barack Obama’s “A Promised Land” one of the 10 best books of 2020. Previously, the paper had listed it as one of their 100 annual “notable” books, a more uncontroversial claim: a 700-page memoir from a recent president is, if nothing else, at least notable. To deem it one of the best books of the year, however, reeks of grading on a curve. It’s good, considering that he’s a famous politician rather than a professional writer. It’s good, considering how much policy detail he needed to include. It’s good, considering.

But isn’t this the refrain of the Obama presidency? All things considered, it was pretty good; no point in caviling at the flaws. Volume one of his presidential memoir takes this as a central theme: When all is said and done, he’s satisfied that he did the best he could.

In “A Promised Land,” Obama does set himself a hefty challenge. There’s no shortage of raw material to cover. He begins by glossing quickly through his personal history (from his childhood to his stint in the U.S. Senate), spends over 100 pages on his 2008 presidential campaign, and then documents his eventful first three years in office in dogged detail.

“What I’m trying to accomplish in this book is both history and a story,” he told the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg. “I think what ended up taking a long time was trying to do both.” At some points, Obama explained, he sacrificed narrative flow in favor of policy detail; at other points, he padded his pages with “really nice description[s]” he refused to cut. (Pity the editor tasked with killing Barack Obama’s darlings.) He hoped, he writes in the book’s introduction, to blend history with a “sense of what it’s like to be the president of the United States,” and with an inspiring personal story of his discovery of purpose in public service.

Perhaps he could have trimmed his 700 pages down by nixing some of the more eye-wateringly dull policy explanations, or by reining in his tendency to wander into poetic riffs on his family, the seasonal charms of the Rose Garden, and the long arc of history. Certainly, he insists, he did not set out to write a two-volume memoir. “Despite my best intentions,” he writes, “the book kept growing in length and scope.” Even after eight years in the Oval Office, he was not yet immune to mission creep.

Opening “A Promised Land,” like electing Joe Biden as president, is an uncomfortably nostalgic experience. The first 200 pages of the book revisit Obama’s political origin story and the electric rush of his 2008 presidential campaign ― his star-making turn at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, his cleverest soundbites and most adroit campaign stratagems, his soaring rhetoric, his decisive victory. There’s a subdued, diminished sort of comfort in calling up the memory of something that once thrilled you before it disappointed you.

Obama, a more-than-capable stylist, renders his campaign vividly, sculpting it into a lively narrative. Each campaign stumble is an opportunity to recount a witty reprimand from one of his more seasoned advisers, and to lay the groundwork for a cathartic moment of triumph when he avoids a similar pitfall later. He overcomes poor performances at a health care forum early in the campaign and in early debates with the help of David Axelrod. “Take whatever question they give you, give ’em a quick line to make it seem like you answered it … and then talk about what you want to talk about,” Axelrod advised. “That’s bullshit,” said Obama. But it’s bullshit that works; he realizes that his job is to “perform while still speaking the truth,” and surges back with sharper showings at later debates. He fondly remembers shutting down Hillary Clinton with his response to a question about why he had so many former Clinton officials advising him if he believed the country needed change: “Well, Hillary,” he commented, “I’m looking forward to you advising me as well.”

By the time he recalls election night, the electric rush of his campaign crackles off the page. It was almost difficult, with the unfamiliar sensation of optimism rising in my chest, to remember what happened next. But, as Mario Cuomo once said, “You campaign in poetry; you govern in prose.” Narratively, the book slams into a wall of policy minutiae and nonstop crises. For historical purposes, one understands the value of documenting Obama’s perspective on every beat of appointing Cabinet members and moving the health care bill out of the Senate Finance Committee, but it has the undeniable effect of resembling a briefing book rather than a literary memoir.

Not that he doesn’t keep trying. In his bid for literary readability, Obama offers neat scenes, snappy dialogue and even cliffhangers, which can feel almost comically genre-ready. After several pages describing Muammar Gaddafi’s bloody crackdown against Libyan protesters in 2011, the escalating global pressure to intervene, and the downsides of instituting a no-fly zone over Libya, he ends the chapter with a line straight out of an action movie: “I think,” he tells the team gathered in the White House Situation Room, “I’ve got a plan that might work.”

Obama also has a taste for characterization akin to that of a seasoned feature writer, summing up world leaders with a few revealing lines. Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, he writes, looks “like a figure out of a Toulouse-Lautrec painting”; Russian President Vladimir Putin has “pale, watchful eyes” and “a casualness to his movements, a practiced disinterest in his voice that indicated someone accustomed to being surrounded by subordinates and supplicants.”

In his interview with Goldberg, Obama explained that his care in describing high-level politicians and foreign leaders was intended to “remind people that these are humans and you can understand them and make judgments.” It works; by humanizing figures like Putin, former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he diminishes the mythic aura that can surround powerful leaders.

But humanizing also has the effect of inviting empathy. Obama can be harsh on occasion ― correctly assessing Sarah Palin as having “absolutely no idea what the hell she was talking about” ― but even his toughest critiques are gentle at their core. Ignorance, after all, is a kinder frame than viciousness, and he rarely ascribes to greed or cruelty what he can ascribe to obliviousness. The bankers who drove the American economy off a cliff are “people who had no doubt worked hard to get where they were, who had played the game no differently than their peers … They gave large sums to various charities. They loved their families.” He claims that he can’t understand the bankers’ outrage over proposed Wall Street reforms, but he spends more time trying to empathize with them than he does condemning them.

In one notable scene, driving to his 2009 inauguration with former President George W. Bush, Obama bristles at protestors lining the streets. “I felt quietly angry on his behalf,” he writes. “To protest a man in the final hour of his presidency seemed graceless and unnecessary.” Throughout the book, he describes his efforts to stay focused on those who need him as a champion ― ordinary Americans who lack health care, who face discrimination, who are under water on their mortgages ― but he often bridles at the audacity of those who make him, and other powerful leaders, too uncomfortable in demanding redress.

Obama’s gift for self-reflection can be a balm, contrasting as it does with our current president. Without wallowing in doubt and shame, he offers insight into his own points of weakness ― a tendency to get bogged down in technocratic details, a seed of selfish ambition ― and often follows his own most troubling admissions with a bit of self-reproach. After describing his noble anger at Bush’s inauguration protesters, he admits to “a trace of self-interest.” After all, soon he would be the one facing protests.

Yet when it counts, Obama often seems to leave things out. In his dramatic recounting of planning for the raid that ultimately killed Osama bin Laden, he emphasizes his concern that a targeted missile strike on the compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, would risk collateral damage: “I was not going to authorize the killing of thirty or more people when we weren’t even certain it was bin Laden in the compound,” he recalls. However, the second part of the sentence, though less noble, was likely the operative one: He wanted to be absolutely sure they got bin Laden. Just a couple of pages later, he makes a glancing mention of “U.S. drone strikes against al-Qaeda targets” which “had been generating increasing opposition from the Pakistani public.” When he revisits his counterterrorism policy, it is with grim satisfaction; his only regret is that he has no choice but to order the deaths of hardened young terrorists rather than save them with education and training. Self-searching and moral high-mindedness about the civilian death toll of his expanded program of drone strikes are tellingly absent.

The memoir genre has long inspired debate about the ethics of using the lives of others — which necessarily intersect with that of the author — as fodder for art (or, if not art, for a product to sell). What if that author is a president whose legacy includes inflicting misery on innocents? Should he profit by selling a book defending his exploits? Those questions have hovered around discussions of a possible future Donald Trump memoir: A fat book contract would be quite the reward for his four years of incompetence, bigotry, corruption and cruelty. “A Promised Land” offers a thought-provoking foil; it’s undoubtedly better, more humane and more illuminating than a Trump memoir would be, and yet there’s something unsettling about seeing a 700-page defense of a former president’s decidedly mixed record touted as one of the greatest books of the year.

Perhaps there’s an upper limit on the value and quality a presidential memoir can really offer, just as — as Obama so often argues in this book — there’s a limit on how much good a president, constrained by the vast fragility of the American economy and global politics, can actually achieve in office. Maybe “A Promised Land” is as good as we could ever expect. Maybe his presidency was too. But maybe that doesn’t mean good enough.

Related

Trending

Source: Read Full Article