TV’s newest commercials are starting to look an awful lot like the web’s oldest.

Any user of Amazon’s Fire set-top device might have recently stumbled upon an interactive on-screen graphic from Geico, the insurance company known for its heavy use of TV ads. In just 15 minutes, the company likes to claim, it can save people money on car insurance. But in considerably less time, Amazon customers who clicked on a Geico-sponsored sign on their Fire home page were taken to a screen where the company offered viewers access to a range of horror movies available on Amazon Prime Video – “Godzilla” and “A Quiet Place” among them – as well as two Geico ads tied to Halloween. Progressive Insurance tested similar Fire outreach a few months earlier.

Neither insurance company made executives available to comment (nor did Amazon), but TV-watchers in an era of streaming video doesn’t need corporate guidance to understand what they might have seen. Amazon, one of the heralds of a new age of watching TV, was making use of online banner advertising – one of the medium’s most annoying concepts.

Madison Avenue has hopes old web formats will gain traction in a new TV-screen frontier, one on which viewers watch fewer traditional video ads but might gravitate to an on-screen component that is just as clickable as one of the graphics that allow them to dive into a favorite series or movie.

“Put yourself on your couch. You are the consumer. What do you want?” asks Cathleen Ryan, vice president of marketing for Intuit, which has run interactive ads for its TurboTax on the Roku streaming hub. “What I don’t want is ‘Hey, look at that 15-second spot.’”

Roku, Hulu and other streaming-video providers that accept ads are betting that clickable modules tucked among their entertainment selections will win consumers’ notice. Hulu before Halloween offered a show called “Trick or Treat,” and subscribers who added it to their “My Stuff” received an email with a unique code that led to a landing page. Some customers who visited that area were able to receive 100 full-sized Butterfinger bars in a container that looked a lot like a coffin. Roku has begun placing interactive “pop-up” overlays on video commercials from certain sponsors who have agreed to let the bottom-of-the-screen modules to surface.

“There is an expectation from viewers that advertising is not going to be disruptive, that it’s not going to be irrelevant to them, “ says Jeremy Helfand, vice president and head of advertising platforms at Hulu. Indeed, earlier this year the company unveiled a “surprise and delight” concept that isn’t for sale in traditional fashion. Instead, a team from Hulu figures out ideas that might work best in its environment and then approaches various parties. Before Mother’s Day, Hulu executives reached out to The Bouqs Company, a distributor of flowers, and teamed up with them to create an interactive module that looked like another show selection on the service. As it turns out, clicking on the selection gave subscribers a chance to win a free bouquet of flowers.

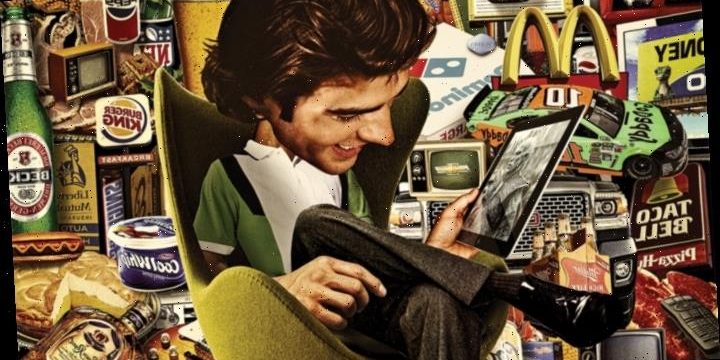

Getting these concepts right is critical for the future of TV. The medium has long hinged on the billions of dollars it receives from big-spending advertisers ranging from Apple to Zyrtec, who spend somewhere around $70 billion annually on TV commercials. Yet a rising generation of new-tech couch potatoes has grown up largely unaccustomed to having to sit through ad breaks. Many of the medium’s most popular streaming outlets – Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney Plus, for example – do not run traditional commercials, a policy that forces ad-supported streaming venues to find new ways to keep money coming in the door without annoying subscribers.

Advertising on connected televisions – display ads on home screens and in-stream video ads – is seen rising nearly 38% in 2019 to $6.94 billion, according to a forecast from market-research firm eMarketer. The company expects that total to surpass $10 billion by 2021. Meanwhile, the company sees traditional TV advertising falling 2.9% to $70.3 billion this year, a total that in 2021 should stay around the same.

At first glance, the banner ad would seem an unlikely vehicle for modern marketing success. The concept first gained traction in the 1980s and 1990s, when online bulletin-board services like Prodigy started running banners at the bottom of their graphic displays.Soon, everyone, it seemed, was using banners. The spread of the digital web in the 1990s was fueled by online banners.

As the little promotional square proliferated, however, the click-through rates they engendered tumbled. Most advertising executives concede that many banners go ignored, and publishers have turned to page takeovers, branded content and other methods to blend advertising into the digital mix.

“The banner ads of old, that was just shotgun,” says Eric Levin, chief content officer at SparkFoundry, the Publicis Groupe media-buying firm. “In the old days, you got 50 different pop ups and it would interrupt your experience.”

In the streaming world, however, the banners may just have more to offer. In decades past, they just took a web surfer to yet another page of information. On the streaming hubs, which have a more direct connection to data about a customer, they can do more – including offer free stuff.

Streaming-video fans are already on the hunt for new programming selections, notes Alison Levin, vice president of sales and strategy at Roku. “The number one thing they are searching for is free content,” so any new interactive ad that can bring them a sneak peek of a movie; a trailer; or a look at a series they might not normally get is often well-received. In turn, Roku research has found “that 50% of consumers are more likely to consider purchasing a brand when it gave them something for free,” she adds. Roku has run interactive ads from Baskin-Robbins, for example, that sent a coupon code that could be redeemed for a treat to a subscriber’s device.

The new concepts don’t mean the banner is suddenly welcome in consumers’ lives. It’s the potential prize, not the pitch, that is getting customers to click. “Banners alone can’t build a brand,” says Cheryl Huckabay, a managing principal of brand media at Dallas ad-agency The Richards Group. “It has to be paired with the right show, the right context,” she adds. “There’s still banner blindness, and they do get ignored.”

Source: Read Full Article