By Robert Moran

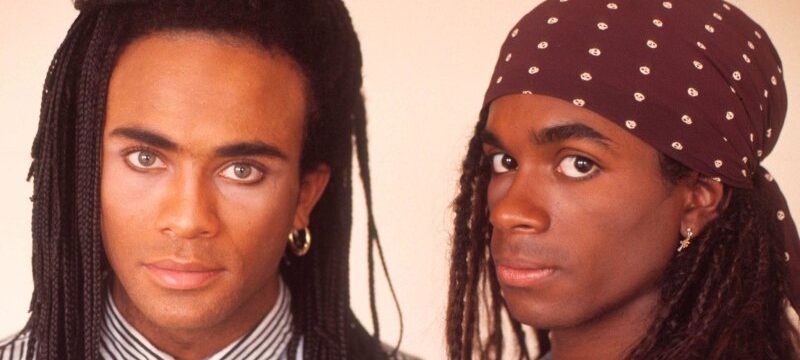

Milli Vanilli in 1990: Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan.Credit: Michael Putland

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Over 30 years on, it makes for ludicrous footage. It’s November 20, 1990, and there’s Fabrice Morvan and Rob Pilatus, barely in their mid-20s, quietly facing a barrage of furious reporters – steaming, ranting, accusatory – after copping to the fact that their chart-topping Euro-pop phenomenon Milli Vanilli was, as one news report put it, “a lot of phoney baloney”.

Viewed through the filter of today’s autotune and avatars and AI, where artifice is an entrenched part of pop’s creative fabric, the ferocity looks ridiculous. But in 1990, the fact Milli Vanilli’s songs – such as Girl You Know It’s True and Blame It On the Rain, global hits that helped sell eight million albums – had been lip-synced was grounds for a public torching.

“That anger [from the press], I didn’t expect it,” says Morvan over Zoom from Mallorca, now 57 but still sporting the same fresh face and locs as he did during Milli Vanilli’s short-lived peak. “It was difficult for me to understand because I was interested in journalism at school; I knew that a true journalist had an oath to investigate, to be impartial, to address every person in the story. But right there, Rob and I were not treated fairly. We were the only ones being investigated! The gatekeepers, the record company, the managers, the PR company, the producer – they ran to the woods.

“They grabbed onto us like we were the ones in charge,” Morvan recalls. “But you know when you look at mob movies, and you look at the boss at the top? The boss was Frank Farian.”

Fab Morvan, at 57: “I’m excited I was finally able to tell my story after 30 years.”Credit: Paramount+

If a tad breezy, the new Paramount+ documentary Milli Vanilli is compelling viewing, even for those of us familiar with pop’s wildest – and most tragic – scandal. Directed by filmmaker Luke Korem, whose previous documentaries focused on grifters of various kinds (sports gamblers, card magicians), the film reframes the duo’s infamy with a modern understanding of the music industry’s parasitic power dynamics. In 1990, the Milli Vanilli story was one of foolhardy and deception, of famef—ers who pulled the wool over an adoring public; in 2023, it’s a cautionary tale of racist exploitation, of corporate greed, of fame’s seduction. It’s also a tribute to Pilatus, who, in 1998 and aged just 32, died from an accidental overdose of alcohol and prescription drugs.

At the film’s core is Farian. A German producer who’d already run the same successful scam with Boney M (Bobby Farrell might’ve been Boney M’s magnetic frontman, but Farian was the voice on the tracks), Farian was Morvan and Pilatus’ opportunistic Mephistopheles. Spotting the pair as backup dancers on German TV and attracted to their good looks, he signed them to a multi-album deal.

“We fell into the trap,” recalls Morvan. “It was a smart move on his part. We were young and hungry. We signed a contract without an attorney, without a manager, without protection.” They received 1500 deutschmarks each, a windfall for two kids from the projects of Paris and Munich. When the money ran out while idly waiting for Farian’s next instructions, they asked for more and were routinely obliged. “It was, ‘Oh yes, of course’ – not knowing that by asking for that money, we were going deeper into it and couldn’t get out of it,” says Morvan.

When Farian finally told them they wouldn’t actually be singing on recordings – instead lip-syncing to the faceless voices of lead Brad Howell, rapper Charles Shaw, and backing vocalists Linda and Jodie Rocco – they were already stuck. “To get out of it, we had to repay all that money. Well, we don’t have the money, so how do we repay? We’re gonna have to work. So we were trapped.”

Morvan and Pilatus with producer Frank Farian (centre), in Munich in 1988.Credit: Getty

Morvan is clear the pair eventually “embraced the lie”. Fame – especially for Pilatus, who was raised in an orphanage (“whenever parents came to adopt a child, he drank water from the toilet bowl to draw attention to himself,” Farian’s secretary says in the film) – proved intoxicating. “The thing is, the deeper you go and taste that life? It was like, wow. Anybody in our shoes would feel that.”

Even as it worked, the charade always felt precarious. In the film we’re shown footage of a live concert in Bristol, Connecticut on July 21, 1989, when the emulator’s vocals start skipping, leaving Rob and Fab to run offstage while the crowd gets rowdy. We’re also shown footage of the pair on The Steve Vizard Show during their promotional tour of Australia in early 1990, where the host repeatedly mocks their accents, suspiciously conspicuous on their recordings. Morvan, particularly, endures it all stone-faced. Living with such a secret, was he ever even able to enjoy Milli Vanilli’s stratospheric success?

“For me, it was a dream-slash-nightmare,” he says. “The place where I felt the best was the stage. It was where we could shine and give everything we had to the audience. In the back of my mind I kept saying, ‘Well, I’m going to give you everything I’ve got, and maybe one day you will forgive me for doing what we did’.

“In the beginning, it felt beautiful, but when the scandal hit, I realised how mean human beings can be,” he says. “It was difficult for us to take that on. I always say Rob died of a broken heart as a result of this love that was taken away. When we lost everything – man, we went in a spiral. To survive the pressure of carrying on this lie, we medicated ourselves, to numb your emotions just so you can keep on working.”

By the time they won a Grammy for best new artist in 1990, the charade was an open secret with a whole industry complicit. While Farian declined to be involved in the doco, it does boast a few smoking guns – mainly ex-executives from Arista Records, who suggest founder and president Clive Davis turned a blind eye when he discovered the ruse (album sales alone, one says, brought in $US580 million). Then Grammys chief Michael Greene, who ran the organisation for 14 years until 2002, also allegedly knew the pair lip-synced during their performance on the night of their win.

Pilatus and Farian, pictured with their Grammys in 1990.

But after the scandal was revealed, Greene rescinded their Grammy and Milli Vanilli became the first, and still only, act to have their Grammy taken away, which is remarkable when you consider the awards’ repeat winners have included convicted criminals such as R Kelly, Bill Cosby and Phil Spector.

“There was such incredible hypocrisy. The requirements at the Grammys was everyone had to perform live – so how did Milli Vanilli manage to not perform live?” Morvan scoffs. “[Greene] even encouraged me when I took a picture with him before the show: ‘Hey, tonight – make sure you do it well…’ That’s what he said!”

When Morvan recalls these moments, there’s not so much anger in his voice but a resigned acceptance that the damage has been done. He’s had years stolen, a life ridiculed, a brother lost. He’d long been looking for an opportunity tell the pair’s tale. Years ago he sold the rights to his life story to Brett Ratner and James Packer’s RatPac production company, with the hopes of a biopic. But Ratner’s #MeToo scandal sunk those plans. Still, the new doco’s just a start.

Milli Vanilli at their final press conference, in November 1990.Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“An hour and 40 minutes is not enough. We can unpack that, because there’s a lot of things we only touched on shortly. So, to be continued,” says Morvan. “But I’m excited I was finally able to tell my story after 30 years… To tell the story from a human standpoint, and to show the inner workings of the music industry.”

Even now, the cruelty endures. Morvan says every few years he spots a new “best of Milli Vanilli” with his face on the front. “And I don’t touch a dime, I don’t get nothing. But that’s okay, I’m a patient man,” he says. “First things first, I’ve proved myself, that I can do this.” He performs – and yes, sings – every weekend, sometimes to 15,000 people, sometimes to 2000, he says. “No matter how many people are in the audience, I give my all. And they don’t forget about me, that’s for sure.”

He’s also come to a sense of appreciation around those classic hits, alongside a savvy audience with a better understanding of the spectacle of pop. “It’s never just been about vocals. People want to jump, people want to dream. We brought excitement, we made people happy. Music is very powerful, it’s like perfume. People made beautiful memories, people made babies because of that music.

“Now they can watch the documentary and understand what happened to these two human beings who were larger than life at one point. Because people thought they knew the story, but they didn’t know.”

Milli Vanilli premieres on Paramount+ on Wednesday.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article