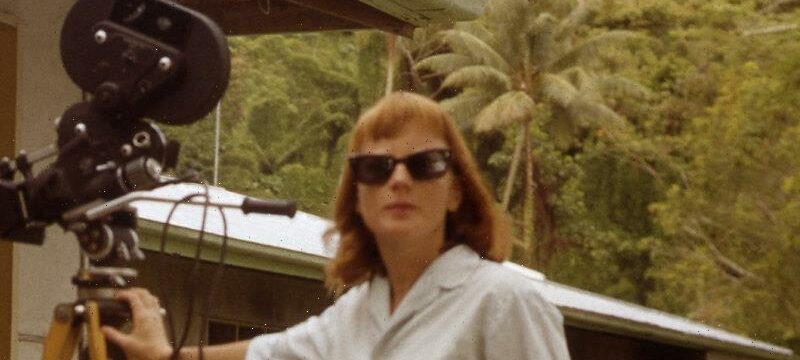

Two decades before Gillian Armstrong directed My Brilliant Career, and well before the emergence of Jocelyn Moorhouse, Cate Shortland and Rachel Perkins, Lilias Fraser was a trailblazer for Australian women making films.

Trailblazing director Lilias Fraser on location for one of her films.Credit:Bonsai

If your first thought is “Lilias who?” you are not alone.

Fraser is barely known despite making more than 40 documentaries, starting with the visually striking short The Beach in 1957. At a time of only limited filmmaking in Australia, she made “nation building” industrial documentaries, including Irrigation Farming in the Riverina (1964), Sugar from Queensland (1967) and Australia’s Wheat (1968).

As times changed, Fraser moved on to more political documentaries with This Is Their Land (1970), which is believed to be the country’s first land rights film, and Women of the Iron Frontier (1990).

Her often-difficult life is the subject of the documentary When the Camera Stopped Rolling, which opens in cinemas on April 21. It is directed by her youngest daughter, Jane Castle, a former cinematographer best known for shooting music videos for Midnight Oil, INXS, Prince and U2 as well as the film Fistful of Flies in the 1990s.

Jane Castle, a former cinematographer who shot music videos for Prince, Midnight Oil, U2 and INXS, has directed a film about her trailblazing mother, Lilias Fraser, who made more than 40 films.Credit:Janie Barrett

The documentary is a celebration of Fraser’s filmmaking but is also an emotional story about the uneasy relationship between a mother and a daughter.

Fraser had to endure an unhappy and violent marriage, debts, divorce, abusing alcohol for a time and dementia before her death in 2004; Castle felt abandoned as a child when her parents would leave her and her sister with other people – sometimes strangers – to shoot films.

In a revealing moment in the documentary, Castle says she realised she became a cinematographer to get closer to her mother.

“On some level I thought that if she can’t come and meet me, I’ll enter her world and maybe we’ll meet there,” she says. “And we did to some degree because we were able to talk about film shoots and lighting and cameras and how to deal with blokes on set. She was a wonderful support.”

Fraser’s unlikely film career started after growing up in Brisbane in a wealthy family that had established a chain of supermarkets. She was part of a young generation who left Australia for London, studying photography and developing an interest in film.

“Tenacity is the key word when it comes to her personality and it’s passed down the generations,” Castle says. “Her dad was this rags-to-riches entrepreneur, with a classic Australian can-do attitude, but she was also inspired by a proto-feminist education at an all-girls school where they instilled into the women that they could do anything.”

Fraser wanted to be an artist but, unable to draw or paint well, turned to photography.

“She had this irrepressible energy so she couldn’t stand being stuck behind a still camera or in a dark room,” Castle says. “When she discovered filmmaking meant she could be outdoors and on the move, she just loved it.”

Fraser tried to get jobs in film but was rejected because she was a woman.

Lilias Fraser on location. Credit:Bonsai

“After she shot her first film single-handedly, The Beach was picked up by the ABC and screened every night before the news,” Castle says. “She wanted to be a cinematographer because she loved doing it.

“She went to Film Australia and said, ‘Here’s my film, I’d like a job’. They just laughed at her and said, ‘You won’t be strong enough to carry the cameras’ and gave her a lowly production assistant job.”

When all the male directors turned down a dull-sounding film about the Torrens title system of land registration, Fraser said she would do it.

“She put her heart and soul into it and made this little film,” Castle says. “Then she got pregnant and they sent her home. They wouldn’t have her at Film Australia being pregnant so she had to set up an editing room in our house to cut the film.”

As a mother, Fraser decided to set up a film company with her husband as the front man.

“She used that difficult situation of being a married woman with kids to her advantage,” Castle says. “Dad went out and got all the work while mum wrote, directed and edited the films.”

Fraser flourished at a time when mining companies, agricultural boards and government departments were funding upbeat, quasi-educational films about building the nation. Castle says her 1970 film Beyond the Boom ran in cinemas for months as a short before the movie.

“There wasn’t much cynicism around then so agriculture and mining were seen as really great things that created jobs and got the nation moving,” Castle says. “She really went with that narrative and threw herself into making really great pieces of work.”

Fraser created a children’s TV drama, The Young Producers, and wrote a script for a feature film but was never able to get it financed. Her work became more political as she realised the importance of land rights and women in the mining industry.

Castle says her mother had no idea of her significance in Australian film history.

“She was one of the first women to really break through the glass ceiling in a very male-dominated Australian film industry,” she says. “And she did it because she loved making movies.”

Producer Pat Fiske remembers that no one at the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op, a hotbed of emerging talent, had heard of Fraser when she took a humble distribution job there after getting divorced in the late 1970s.

“It was like, ‘Who is this woman?’” she says. “She’d been making films since the late ’50s and nobody knew her.”

Fiske says Fraser was a very funny woman who was always upbeat: “Making the film with Jane, I know it was not all roses but she was amazing in covering up what was happening.”

Castle gave up cinematography when she realised her work in the US on schlocky horror films like Leprechaun 2 and music videos “did not in any way come close to my personal values”. She became an artist and activist and is now studying to be a psychotherapist.

Over eight years the documentary evolved into a mother-daughter story.

“Part of me was still a bit pissed off,” Castle says. “We’d lived this quite chaotic early life with our parents going off on location all the time and leaving us with people. There were still unresolved issues to be honest between my mother and I.

“I wanted to look the other way. But in the end it was good because I learned a lot about her and I came to understand her motivations and her own history. There’s a lot of healing in the film as a result.”

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Email the writer at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter at @gmaddox.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article