Faced with the biggest New York City fiscal crisis in nearly two generations, the state’s Financial Control Board has punted. The board decided last week that the city’s budget isn’t balanced but not quite imbalanced enough to qualify as an emergency. The inaction demonstrates a grim reality: In the ’70s, when the state created the FCB, New York state was in a political position to rescue the Big Apple. No more.

The FCB is part of the fable that Gotham’s Wise Men tell about the Bad Old Days. In 1975, when the city’s lenders cut off New York City from borrowing, pushing it to the brink of bankruptcy, the state Legislature and Gov. Hugh Carey passed a law. The Financial Emergency Act enabled the new board, heavy with financial experts, to control the city’s budget. (The governor controls four out of seven members.)

For 11 years, the board did good — most importantly, freezing government wages. In the Ed Koch administration, during the early ’80s, the board served as “bad cop” when unions asked for high raises; Koch could say the board wouldn’t let him.

But New York never got its fiscal house in order. The board was also a pioneer in what would become the global economy’s mantra, starting in the ’80s: If you’ve borrowed too much already, just borrow more.

In the mid-’70s, banks thought that New York had borrowed too much money, to pay for day-to-day expenses, not long-term infrastructure. The solution, approved by the board, was for the city to borrow more to pay off those bankers. We still owe that money.

Longer term, New York got lucky. In the early ’80s, Wall Street took off, ironically because of the global debt boom. In 1980, city spending, including only local dollars, not federal and state aid, adjusted for inflation, was $29 billion. In 2019, it was $69 billion.

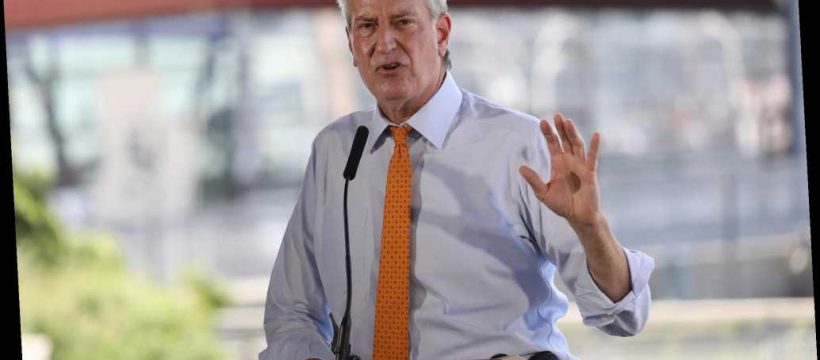

We still borrow for operating expenses. The city owes $108 billion for future public-sector retiree health-care costs, money the city should have set aside when the future retirees were doing the work. In October, Mayor Bill de Blasio is set to pay teachers and civilian workers a $1.5 billion delayed raise he approved in 2014, for work they did a decade ago.

Now that the city’s luck may have run out, will the board step in? The board must certify that the city’s budget is balanced every year — or else.

Last week, at the meeting to make this determination, the board’s report was tough — slamming de Blasio’s plan, approved in June by the City Council, to close a projected $9.7 billion drop in revenues.

The board picked apart de Blasio’s pretensions, beyond his closing most of the gap with one-shot sources that won’t be available next year.

Of de Blasio’s $1 billion in “unspecified labor savings,” the board’s staff noted: “We have no details on . . . these savings.”

If threatened layoffs are “a viable backup, the city must develop a detailed plan on how and when the layoffs would occur.” Of nearly $400 million in overtime savings: “The city has never shown it can control overtime.”

On federal aid: “The city cannot wait.”

Overall, the staff determined the city likely faces a $2 billion gap for the fiscal year that just started July 1, an imbalanced budget.

So, what’s the “or else”? The board told de Blasio to try again — resubmitting a new plan. If the city is spending nearly $6 billion a month, nearly two months into an imbalanced budget, why not take over the city’s finances now, imposing new wage freezes?

Simple: The board has no powers. Effective with reforms to the Financial Emergency Act made nearly 20 years ago, the board can no longer re-impose a “control period.”

It must go to . . . the state Legislature. But left-wing freshmen lawmakers are highly unlikely to enact a “control period” that enables wage freezes.

Municipal bondholders may figure out that when it comes to a balanced budget, New York long ago defanged its “bad cop.”

Nicole Gelinas is a contributing editor of City Journal. Twitter: @NicoleGelinas

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article