More On:

parole

Slain NYPD cop’s kin seek to stop his killer’s role in police reform

De Blasio blames state parole system for Midtown attack on Asian woman

Blame NY’s soft-on-crime approach for horrific Midtown hate-crime attack

Letters to the Editor — April 1, 2021

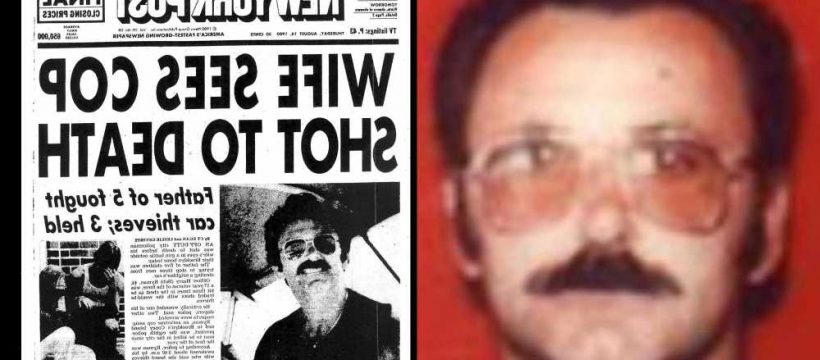

The daughter of a veteran NYPD officer murdered four decades ago is disgusted that her dad’s killer was recently sprung on parole — even after he insisted the slaying was in self-defense, while refusing to apologize, new transcripts revealed.

Paul Ford, who was convicted in Harry Ryman’s 1980 death during a car theft gone wrong in Brooklyn, was released on parole on March 23, according to state records.

Ryman’s family staunchly objected the move.

“You know, I used to feel strongly that our victim impact statements really mattered,” the late officer’s daughter, Margaret Ryman, told The Post last week.

“I thought that the parole board really wanted to know how these crimes impacted my brothers, my sisters, my mother. You know, all the things that we grew up without, all the things that we had to go through.”

She added, “I actually think it’s really disgusting. I actually feel like that’s not justice. That’s totally not justice.”

Ryman’s son, Edward Ryman, said Ford’s release “devastated our family.”

“My father couldn’t walk down the aisle with my sisters,” he said. “He couldn’t see our grandkids. My mom had to raise five kids by herself.

“Our family is heartbroken.”

Transcripts of the Feb. 9 parole board hearing that prompted Ford’s release — obtained by The Post under the state Freedom of Information Law — show that the killer showed little remorse and took minimal responsibility for Ryman’s murder.

Ford admitted that he remembered Ryman identifying himself as a police officer before the fatal shooting around 3:40 a.m. on Aug. 15, 1980. The 17-year NYPD veteran was off duty and home in Brooklyn when he tried to stop Ford and two others from breaking into a car across the street.

Ryman, who was 43 and a married father of five at the time, exchanged gunfire with the suspects but was fatally shot three times in the chest.

“Why’d you shoot at him if he identified himself?” asked parole board commissioner Elsie Segarra followed up.

“I shot at him in self-defense,” Ford claimed.

Later on in the hearing, Segarra asked the convicted murderer why he took his case to trial.

“Because I wasn’t guilty,” Ford replied.

“Why did you say back then you were not guilty, do you find yourself guilty now?” Segarra asked. “Do you take responsibility?”

“Yeah,” Ford said. “I take responsibility.”

Asked if he had anything to say to Ryman’s family, Ford only said: “I feel bad.”

A second parole commissioner at the hearing, Otis Cruse, didn’t ask any questions, according to the transcript.

Ford’s lackadaisical replies not only enraged the Ryman family — which includes a grandson who is an NYPD officer — it riled the city’s Police Benevolent Association.

“Paul Ford and his associates killed PO Harry Ryman because he was attempting to arrest them for a crime,” PBA President Pat Lynch said in a statement.

“That’s not self-defense. It’s an attack on every law-abiding New Yorker. The Ryman family has suffered horribly, but the politicians who are allowing the parole board to run amok could not care less.”

Ford, Barrington Young and Cornelius Bucknor were convicted in Ryman’s death.

Young and Cornelius Bucknor have also been paroled.

Ford, who turns 59 on Friday, has had “a number of misbehavior reports” while in prison — most recently in August for smoking, according to the parole hearing transcript.

Prior to that, his most recent disciplinary gaffe was in 2012, the board said, without providing further detail.

In a statement Thursday, officials at the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision said parole board decisions are based on standards dictated by state law.

“Prior to making a final decision, the board members must follow the statutory requirements which take into consideration many factors, including statements made by victims and victims’ families, if any, as well as an individual’s criminal history, institutional accomplishments, potential to successfully integrate into the community, and perceived risk to public safety,” the statement said.

“Additionally, by statute, the board considers any recommendations concerning release to community supervision from the district attorney, sentencing court, and the defense attorney,” the department said.

Ford could not be reached for comment.

State officials redacted portions of the transcript that discussed where he would live after his release.

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article