That’s one hell of a Korea move! For Bong Joon-ho, the director of Parasite, the plot of his Oscar-winning tale of haves and have-nots exploiting each other has a personal meaning – it’s based on his own life story…

- Parasite made history by becoming 1st foreign language film to win Best Picture

- Bong Joon-ho’s film became the first South Korean film to win Oscar of any sort

- Was inspired by Bong’s experience as maths tutor to son of wealthy Seoul family

- His first taste of how the other half live was a job as a tutor to the son of a wealthy Seoul family

There’s a moment in the quirky black comedy thriller Parasite where the rich, smug owners of a perfect home get the shock of their lives, when strangers suddenly turn up at a cosy family get-together.

It was reminiscent of the scene at Sunday’s Oscars, when Hollywood’s finest gasped as a group of South Koreans crowded onto the stage, after stealing the night from the odds-on favourite, Sam Mendes’s 1917.

Parasite made history by becoming the first foreign language film to win Best Picture, the top award. In fact, it became the first South Korean film to win an Oscar of any sort.

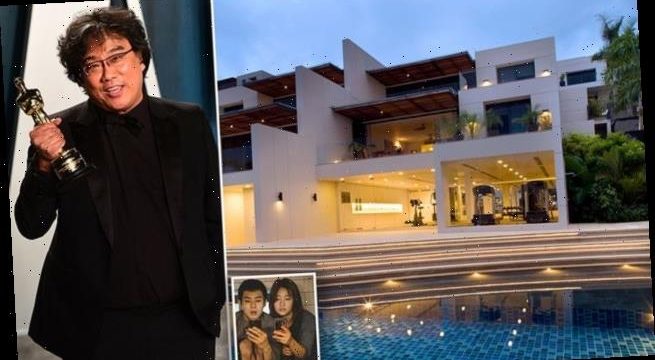

Bizarre as the plot for Parasite may be — a dirt-poor family in South Korea’s capital, Seoul, craftily inveigles itself into the home of a wealthy family — it was inspired by the 50-year-old director’s own experience. Pictured: A luxury Korean home

It was particularly surprising as, while one million people have flocked to see the film in South Korea, relatively few have bothered to seek it out in the UK and U.S. — despite it winning the coveted Palme d’Or at Cannes.

It also won Oscars for Best Original Screenplay and Best International Film, and its gifted director Bong Joon-ho, who was named Best Director, couldn’t hide his delight. ‘When I was young and studying cinema there was a saying that I carved deep into my heart,’ he said in his acceptance speech. ‘The most personal is the most creative.’

The saying, which he borrowed from his film-making hero Martin Scorsese, certainly applies here. Bizarre as the plot for Parasite may be — a dirt-poor family in South Korea’s capital, Seoul, craftily inveigles itself into the home of a wealthy family — it was inspired by the 50-year-old director’s own experience.

The son of a graphic designer and a housewife, Bong grew up in modest circumstances in the South Korean city of Daegu, and then its capital. It was in his early 20s, around the time he was involved in student demos against the country’s military rulers, that Bong got a taste of how the other half live. He got a job as a maths tutor to the son of an enormously wealthy Seoul family.

It also won Oscars for Best Original Screenplay and Best International Film, and its gifted director Bong Joon-ho (pictured), who was named Best Director, couldn’t hide his delight

His girlfriend — now his wife of more than 20 years, Jung Sun-young — was teaching the same boy English and suggested Bong as a ‘trustworthy friend, even though I was actually really bad at maths’, he says. ‘That’s how it works with those jobs. It’s not as if they put out lots of ads looking for domestic help —you’re introduced.’

And that is pretty much how the entire Kim family in Parasite manages to find work at the home of the wealthy Park family.

The film has been hailed as a spiky class-war drama, but Bong insists it’s really about the polarisation of society. For him, it has no real villains. Both families are ‘parasites’, he argues: the poor Kims are clearly exploiting the rich Parks, but the latter are leeching off the former’s cheap labour.

Until they meet the Parks, the Kims are scraping by, folding pizza boxes for money. Then the son, twentysomething Kim Ki-woo, gets a job as the Parks’ teenage daughter’s English tutor.

He sees an opportunity, and gets his younger sister a job teaching art to the family’s troublesome little boy. One thing leads to another, and soon the Kim patriarch (played by Song Kang-ho, one of South Korea’s most feted actors) is hired as a chauffeur, while his wife becomes the housekeeper. Their employers are not entirely clueless, so the Kims must make sure they never let on that they are related, or their ruse will unravel.

The huge disparity between the families is most graphically illustrated through their homes, where most of the action is set.

The Kims live in a miserably tiny, dingy semi-basement, which is at the bottom of the heap in every way — they live at the bottom of a hill, the Parks at the top.

They’re so far down the pecking order that, because they live below the sewer line, their only lavatory has to sit on a high ledge to avoid the waste water backing up.

A single narrow window near the ceiling lets some daylight into what passes for a living room, but the window is urinated on by drunks. Flood water and fumigation gas also comes straight in. The family fight over the one corner of their home where they can get free wi-fi.

Pretty much everything in Parasite seems to be symbolic, and their miserable home ‘really reflects the psyche of the Kim family’, says the director, adding: ‘You’re still half overground, so there’s this sense that you still have access to sunlight and you haven’t completely fallen to the basement yet. It’s this weird mixture of hope and this fear that you can fall lower.’

Such places exist in abundance in Seoul, a packed city of nearly ten million. Named banjiha, they cost around £350 a month to rent. Poor and young Koreans trying to get a toehold on Seoul’s housing market are their main inhabitors.

The film has been hailed as a spiky class-war drama, but Bong insists it’s really about the polarisation of society. Pictured: A scene in the film

Often boasting bathroom ceilings so low you cannot stand upright in them, the flats become unbearably humid and mouldy in the country’s hot summers, and tend to stink.

Bong, known for his attention to detail, scoured Seoul’s banjihas for props for the Kims’ cluttered home. His acquisitions included a fridge that was reportedly so smelly it was never opened on set. The home and its street were constructed in a giant water tank (for reasons that become clear in the film).

Bong’s intensive research extended to the characters — he had a script-writing assistant spend months interviewing chauffeurs, housekeepers and tutors in wealthy areas of Seoul. Pictured: Bong Joon Ho and producer Kwak Sin Ae

Banjihas are a product of South Korea’s uneasy recent history. In 1970 the South Korean government, alarmed by the military threat from communist North Korea, changed its building codes to ensure new apartment blocks had basements that could serve as war bunkers.

Although renting them out as homes was initially illegal, officials were forced to relent during Seoul’s housing crisis in the 1980s.

When it comes to the Parks’ vast, sleek home, Bong says, damningly: ‘They want to show off that they have this sophisticated taste.’

Although it’s almost empty, their living room is far bigger than the Kims’ home. Its floor-to-ceiling window looks out on to a perfectly manicured lawn — a contrast to the Kims’ squalid outlook. But the house is sterile — perhaps a clue that, inside it, all isn’t quite what it seems.

Bong’s intensive research extended to the characters — he had a script-writing assistant spend months interviewing chauffeurs, housekeepers and tutors in wealthy areas of Seoul. If Parasite is anything to go by, their experience wasn’t always a pleasure.

The second half of the film is packed with plot twists. ‘It was like when you have water draining in the sink,’ says Bong. ‘At first, you barely notice the waterline descending, but near the end, you start to hear a gurgling as everything rushes down the drain.’ It’s an apt metaphor for a movie whose ending is shocking but also moving.

Bong, whose past films included the gritty sci-fi thriller Snowpiercer (starring Chris Evans, Tilda Swinton, John Hurt and Jamie Bell), never expected Parasite to make a profit as the plot was so ‘weird’ (and it was in Korean).

But grasping his trophies on Sunday, he acknowledged that ‘rich versus poor’ was a universal theme. And they don’t come much richer than the Hollywood elite that ended up cheering themselves hoarse for Parasite at the Oscars.

Source: Read Full Article