Founded in 2008 by a quartet of Harvard and MIT economics graduates, the charitable startup GiveDirectly has become one of the world’s fastest-growing nonprofits by virtue of its simple but innovative approach to raising funds for underprivileged communities. Allowing predominantly Western donors to make direct, unconditional cash transfers to poverty-stricken East African individuals via their phones, the concept cuts out the intermediary factors of larger charities — where televisually induced donations of a few dollars a month might have little direct effect on those in need. On the face of it, it seems a sound idea, and at the outset of Sam Soko and Lauren DiFilippo’s smart, calmly probing documentary “Free Money,” you might be forgiven for expecting a thinly disguised, feature-length infomercial for GiveDirectly itself.

Neither the charity nor the documentary, however, work exactly as they initially appear to. What begins as a generous, receptive platform for Michael Faye, the affable face of GiveDirectly, evolves, by gradual degrees, into a patiently investigative interrogation of their pioneering economic model, as well as the deficiencies and hypocrisies of the psychology driving much First-to-Third World charity. Healthily skeptical but not damning, and generally prioritizing human interest over political polemic, this gripping, broadly accessible breakdown of a globally resonant subject boasts few stylistic or rhetorical fireworks, but is sure to find a home with doc-friendly distributors and streaming platforms following premiere slots in Toronto and IDFA.

For Kenyan docmaker Soko, this is a more restrained, less rousing work than his Sundance-awarded 2020 electoral campaign study “Softie”; he and fellow director DeFilippo take an open-eared journalistic approach to a potentially touchy subject, allowing viewers to draw their own conclusions from the hard facts, procedural observations and grassroots interviews gathered in a tight 78 minutes. Entrusting this subject to Kenyan and American co-directors is a clever move both optically and practically, and “Free Money” feels duly balanced without resorting to timid both-sides-ism.

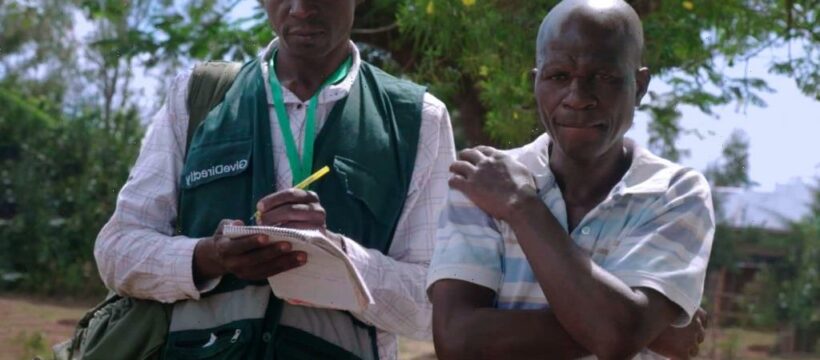

The film begins cutting sharply back and forth between the impoverished rural Kenyan village of Kogutu — the focal point of GiveDirectly’s selective trial run — and GiveDirectly’s sleek Manhattan HQ, where Faye enthusiastically outlines his mission, rejecting the old “give a man a fish/teach a man to fish” proverb by advocating for no-strings, shame-free giving, and aligning himself with the social ideal of a universal basic income. (Cannily selected archival news footage shows how many on the American right rejected the idea, until the COVID crisis brought it closer to home.) Back in Kogutu, potential beneficiaries are guarded when the project is explained to them. “Nothing is ever free,” one villager opines, while others fear the spiritual impact of “dirty” money. A local priest counters that getting money can never be bad — so long as a percentage of it is given to the Church.

Over time, however, some embrace the program, improving their homes and even forming community savings pools with the cash that magically pings into their phones. Others, however, are left out of the loop. A pedantic administrative clause sees young woman Jael ruled ineligible for GiveDirectly donations while her friends’ lives take a turn for the better — her story stands for those of many others excluded by an enterprise that, by Faye’s own admission, is experimental and selective.

Is it fair to “experiment” this way on human lives already feeling the cold shoulder of social inequality? Doughty BBC journalist Larry Madowo, who’s Kenyan-born and U.S.-based, examines the individual lives at stake and takes such hard ethical questions to Faye, who doesn’t have answers at the ready. “Free Money,” in turn, avoids severe final judgments about a program whose first trial phase will only conclude in 2031. Still, Soko and DeFilippo’s pithy, powerful film ultimately signals its solidarity with people who don’t have nine years to wait and see how their lives might change.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article