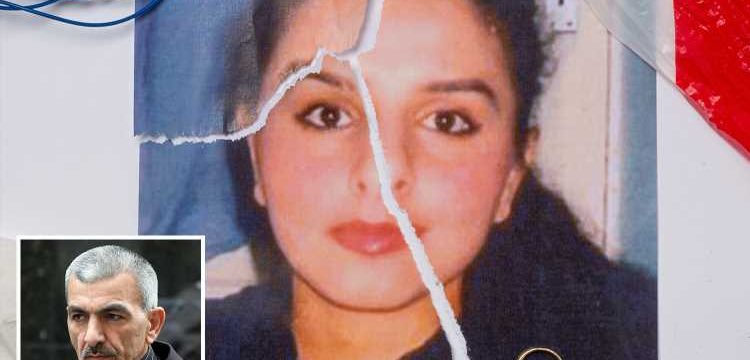

DETECTIVE chief inspector Caroline Goode had been searching for Banaz Mahmod for three long months when she found her, buried in a suitcase in a deep hole in the back garden of a house in Birmingham.

The 20 year old had been raped, then kicked, stamped on and strangled to death with the help of her own family, simply because she had fallen in love.

“As a homicide detective, I was determined to bring every killer to justice,” Caroline says, speaking exclusively to Fabulous. “With most murders, part of the motivation is achieving justice for the family."

"However, in this case, I wanted to get justice for Banaz, in spite of those family members who had killed her and those who wanted the perpetrators to get away with what they had done.”

Actress Keeley Hawes will soon take on the role of Caroline in ITV drama Honour, which tells the story of Banaz’s horrific murder.

The first time Caroline, then a senior detective at Scotland Yard, heard the name Banaz Mahmod was on January 25, 2006, when she got a call informing her that the young woman had been reported missing by her boyfriend Rahmat Sulemani.

She quickly realised that this was more than a standard missing person’s case. “Banaz had made several allegations to police that her father had tried to kill her and that her uncle had threatened to kill her,” she explains.

RAPED & STRANGLED TO DEATH

“And even though she used to text Rahmat several times a day, from the morning of January 24, 2006, there was nothing.”

Banaz was born in Iraqi Kurdistan but came to Morden, south London, with her family as an asylum seeker in 1998, aged 13, fleeing Saddam Hussein’s regime.

The first time she came to the attention of police was on October 10, 2005, when the 19 year old walked into Mitcham police station saying she had been abused by her 34-year-old husband Ali Abbas.

The marriage had been arranged by Banaz’s father Mahmod Mahmod in 2003, when she was just 17, and the horrific abuse that Banaz suffered was documented in a video taken by police.

“He was a strict husband,” says softly spoken Banaz on camera. “Whenever he wanted to have sex, it was just his way – he wouldn’t take no for an answer and he would just start raping me.

He said to me that he’d kill me if I said anything to anyone. I didn’t know if this was normal in my culture or here.”

After two years, Banaz could take no more and walked out on Abbas, moving back to her parents’ house and telling them she wanted a divorce.

“A big part of ‘honour’ is protecting your family from becoming the subject of negative gossip,” explains Joanne Payton from the Honour-Based Violence Awareness Network.

“If a marriage ends in divorce it’s considered to reflect badly on the whole family – that means that if one of your daughters gets divorced, then it might be harder for your other daughters to find husbands, causing your family to lose status in the community.”

According to Karma Nirvana, a charity for victims of honour-based violence, the latest data points to 12 killings taking place in the UK every year. But in reality, this is thought to be the tip of the iceberg.

My husband wouldn’t take no for an answer and he would just start raping me

“Honour-based abuse often goes undetected, and as such goes under-reported in police and prosecution statistics as it’s compounded by a barrier of shame,” reveals Natasha Rattu, a barrister and Karma Nirvana’s executive director.

When Banaz realised she was being followed each time she left the house by men who shouted at her to get into the car they were driving, she went to police.

It’s never been established who the men were, but she was certainly living in fear of her life – particularly after her father and his younger brother Ari heard whispers that she had secretly begun dating 27-year-old Iranian Kurd Rahmat Sulemani.

The couple were fully aware that no one in Banaz’s family or the wider community would accept or tolerate their relationship, because Banaz was technically still married and was deemed to be being openly adulterous.

When one of her cousins spotted Banaz and Rahmat kissing outside Morden Tube station on December 2, 2005, her uncle Ari was quickly alerted.

Ari called a meeting of male family members at his home in Mitcham, where it was agreed that Banaz and Rahmat were bringing shame on the family and must be murdered.

Banaz’s mother Behya was told of the decision, but broke rank by telling Banaz who, unknown to anyone else, went to the police again, this time with a letter she’d written.

Dated December 12, 2005, the letter names the men who wanted her dead as Mohamed Hama and her cousins Mohammed Ali and Omar Hussain.

“They are ready to do the job of killing me and my boyfriend. This was said by my uncle, Ari Mahmod, while on the ‘fone to my mum on December 2, 2005 [sic]” it reads.

On New Year’s Eve, Mahmod told his daughter they were going to her grandmother’s house in Wimbledon to discuss her divorce from Abbas.

'Honour-based abuse often goes undetected'

He asked her to carry a large, empty suitcase from the car into the living room when they arrived. With the curtains drawn, Mahmod then forced Banaz to drink brandy.

He put on Reebok trainers and surgical gloves and told her to sit down because she would soon begin to feel sleepy.

Terrified, Banaz obeyed her father, but knew she needed to escape. When Mahmod left the room, she ran into the back garden and smashed a neighbour’s window with her bare hands to try to get help.

When no one came, she stumbled out into the street and collapsed, bleeding, outside a cafe, where an ambulance was called.

The paramedics who attended described her as being so frightened that she wouldn’t leave the ambulance until a security guard was present. But when police arrived at the hospital, her story was dismissed as being too outlandish to be believed. →

Banaz’s boyfriend Rahmat came to pick her up and the pair went back to his house. They stayed there until Mahmod begged his daughter to come home and convinced her that she would now be safe.

“When she left the hospital after the New Year’s Eve attack she had told nursing staff that her family would kill her if she returned home,”

Caroline says. “But her family promised her nothing would happen to her, and she really wanted to believe that. She loved them and didn’t want to bring any further shame on them by staying away.”

After returning home on the morning of January 24, 2006, Banaz was raped and strangled to death in the living room of her parents’ house by Mohamed Hama – who had been hired to do the job – as her cousins restrained her.

When the two-and-a-half-hour ordeal was over, her lifeless body was forced into the suitcase and dragged out to the boot of a car.

'System failed her badly'

Honour, which ITV is due to start filming next month, will attempt to tell the story of the murder investigation that followed after Rahmat informed police that his girlfriend was missing.

BAFTA-winning Keeley Hawes has said of the role: “In a time when honour killings are still rife, it is critical to shine a light on such an important subject.”

During the course of the investigation, Caroline’s team were repeatedly lied to by members of the Kurdish community.

“In Banaz’s case at least 50 members of the community were involved in the murder, whether in the planning, the murder, disposing of the body or providing false evidence to hamper the investigation,” she reveals.

Hampered by this false information, weeks wasted away and Caroline’s team were no nearer to finding Banaz. But what they did have was Mohamed Hama in custody, charged with threatening Rahmat two days before Banaz was murdered.

As Hama was held in prison waiting to appear in court, his phone conversations were covertly recorded. Records had shown links to Birmingham and properties linked to him were under surveillance.

“He was talking to a Kurdish man who lived in Birmingham”, reveals Caroline. “They were talking about the police being too stupid to find the body, and Hama asked the other man whether he had put the freezer back on top of the patio.”

Caroline realised that on the surveillance footage from Birmingham, a freezer could clearly be seen in one of the back gardens of a house. There, buried 6ft down, the team found the suitcase containing Banaz’s body.

Banaz’s father Mahmod Mahmod and uncle Ari Mahmod both entered a not guilty plea at their Old Bailey trial in June 2007.

On June 11 they were convicted of murder, with Mahmod Mahmod sentenced to serve at least 20 years and Ari Mahmod at least 23 years. Hama had already pleaded guilty at an earlier hearing, and was sentenced to 17 years.

They are ready to do the job of killing me and my boyfriend

Banaz’s boyfriend Rahmat gave evidence twice during the trial and heard gruesome details of the murder, including the fact that it had taken Mohamed Hama more than half an hour to kill Banaz by strangling her with a shoelace.

In 2016, 10 years after her murder, Rahmat was found hanged at his home in Poole, Dorset. He had never got over the horrors he heard in court about his girlfriend’s death.

Banaz’s mother didn’t appear as a witness and investigating officers believed that she could have done more to help her daughter.

“Evidence was heard that Banaz’s mother had offered to get false alibi statements for her husband,” says Caroline.

"And while one of Banaz’s sisters had to go into hiding after she risked her life to give evidence that convicted her father and uncle, another came to court to give evidence on behalf of her father.”

Banaz’s cousins Ali and Hussain had fled the UK for Iraq immediately after the murder, where Caroline’s team heard that they were talking openly about what they had done.

“What kept me going was the fact that I was receiving information that the two who had fled were boasting about their exploits. I had convicted her father and uncle, but that was only half a job,” she says.

“There were several points at which I thought the extradition wouldn’t happen, but I wasn’t going to let those two get away with her murder if it was humanly possible.”

After relentless pressure from Caroline, the men became the first suspects ever extradited to Britain from Iraq, and in 2010 were each handed life sentences.

Caroline’s success delivering Banaz’s murderers to justice was one of the reasons that she was awarded the Queen’s Police Medal in 2011.

'She had faith in the system'

But an Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) report in 2008 made it crystal clear that Banaz’s murder could have been prevented if only police had listened to her.

“The truth is that very little was done for Banaz,” says Caroline. “She had faith in the system and the system failed her badly.”

The report was scathing about the way that officers had treated Banaz, citing “insensitivity and a lack of understanding”, and it’s likely that Banaz would be alive today if police had taken her statements seriously when she came to them.

“I do think that raising awareness of honour killings is one of the biggest things we can do and that needs to be across the board, not just police,” argues Caroline.

“It needs to be teachers, social workers, doctors, nurses, dentists, midwives, housing officials, registrars and counsellors.”

Karma Nirvana’s Natasha adds: “The disheartening reality is that many police officers are still not trained to understand and respond to honour-based abuse.”

“Banaz loved her family very much indeed, and of course she loved Rahmat,” says Caroline. “In the end, it was trying to love both her family and her boyfriend that led to her death.

In Rahmat she found true love, and because of that she was murdered.”

Source: Read Full Article